Barings Bank

EthicalSystems.org Case Study: Barings Bank

A collaborative effort by Jennifer Fang and Joshua Elle

“As my noble friend Lord Hollick argued, trading is all about the control of a collection of

rogues—of strongly motivated, financially entrepreneurial dealers.” –Viscount Chandos, 1995

Overview:

Sir Francis Baring (left), with brother John Baring and son-in-law Charles Wall, in a painting by Sir Thomas Lawrence Sir Francis Baring (left), with brother John Baring and son-in-law Charles Wall, in a painting by Sir Thomas Lawrence |

Barings Bank, founded in 1762, was one of the world’s oldest merchant banks, renowned for having facilitated the Louisiana Purchase. The bank declared bankruptcy in 1995 after losing £827 million (approximately $1.3 billion) due to unauthorized trading activities from one of its employees, Nick Leeson.

- Historical context–“Corporate Portrait: The Economic Might of Barings Bank”

Barings bank was founded in 1762 and declared bankruptcy in 1995 after losing billions due to the actions of one employee. |

What happened?

As Barings Bank’s head derivatives trader in Singapore, Nick Leeson was approved to arbitrage derivative contracts listed on both the Osaka Securities Exchange and the Singapore International Monetary Exchange. The approved strategy was to buy on one exchange and sell on the other for a small profit. However, instead of arbitraging, Leeson made directional bets on the futures contracts (and other derivative instruments) by buying and holding them. He started losing money on his positions, and decided to increase the size of the bet, using money from other areas of the bank to cover his losses. This continued for 2.5 years until the Kobe earthquake caused a sharp decline in the Asian markets, which resulted in the £827 million loss for Leeson and Barings Bank.

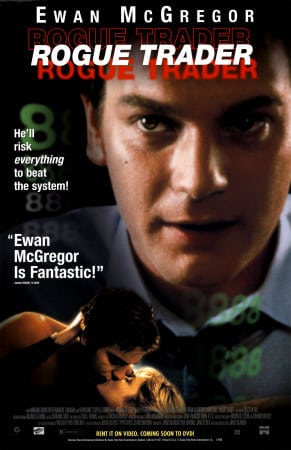

Rogue Trader is a 1999 film directed by James Dearden and based on Leeson’s story. Rogue Trader is a 1999 film directed by James Dearden and based on Leeson’s story. |

What was the system failure?

Barings Bank had many deficiencies in its risk management policies and procedures that allowed for Leeson’s blatant abuse. The most prominent deficiency was that Leeson headed both the trading desk and the settlement operations; duties usually filled by separate people. In other words, Leeson was able to settle and account for his own trades, which allowed him to hide his fraudulent activities. Not only was Leeson able to hide his losses of £200 million, in 1994 he actually reported a profit of £102 million, which ammounted to 10% of Barings’ annual profit.

- Preview for the 1999 film starring Ewan McGregor–“Rogue Trader”

Singapore’s emblematic Merlion stands in the foreground, while its financial district towers in the background. Singapore’s emblematic Merlion stands in the foreground, while its financial district towers in the background. |

Lessons learned:

In the wake of the collapse of Barings Bank, not only did financial companies become more vigilant of the need to separate the control groups from the trading groups, regulators across the world also became more aware of risk management. Currently, the FDIC recommends that all banks ask their employees (especially those who are in risk taking and managing roles) to take an annual consecutive two-week vacation, as an internal safeguard against fraud.

Has this heightened vigilance and separation proven effective in controlling the “collection of rogues?” Or do the situational factors created by high profits and misaligned incentives continue to promote the same willingness at all levels to overlook accounting anomalies and to fail to dig deeper with a level of diligence that is truly due? Can we effectively promote a culture of longer-term investment/trading rather than one of short-term gambling? How can we better instill a true, dynamic awareness of risk management in organizations, where compliance and ethics programs aren’t mindlessly followed limits on bad behavior, but rather where they are living practices toward good behavior within the organization and without? Read more on EthicalSystems.org, specifically our Accounting, Compliance & Ethics Programs, Contextual Influences, and Corporate Governance pages.

- Subsequent perspectives—“Nick Leeson Keynote Speaker” & “Nick Leeson on Newsnight with Jeremy Paxman”

© 2014 by EthicalSystems.org—Anyone may modify and share this document as long as origination credit is attributed to EthicalSystems.org