Workplace Political Polarization

Political polarization in the United States is increasing more rapidly than among other democratic-style governments (Brown University, 2020; Pew Research, 2014) and becoming more problematic in terms of workplace civility and productivity (Dinkin, 2022; Telford, 2022). The left and right each blame the other for becoming more radical; what is certain is that the distance between political parties and voters has grown from crevice to chasm. With this has come the mostly incorrect belief that human beings on the other side harbor ill intentions, support violence, or are otherwise worthy of scorn. As it shifts from disagreement to dehumanization, this trend poses a threat to physical and psychological safety in the workplace because political rifts can seem to justify mistreatment of others.

Polarization can be dissected into three facets (Wilson et al., 2020): affective (how people feel about their allies and opponents); ideological (what people believe and why); and false (exaggerated perceptions of differences and blindness to common ground). While these characteristics are interwoven and work synergistically to drive polarization in general, they also have crucial differences in their antecedents and consequences.

This research page presents a comprehensive review of the factors leading to the current state of extreme polarization and the resulting effects on the workplace, and it explores various potential solutions. Every effort has been made to avoid judgments about the right-left paradigm and to focus on consistent social and psychological factors that are applicable in understanding and responding to political polarization.

In general, it seems that polarization results from information “bubbles” and echo chambers whereby selective consumption of content from social media and news sources leads to decreased awareness and understanding of opposing views. People are not good at detecting bias, misinformation, or fake news. But there’s much more to this process, which originates in shared human psychological processes and behavior.

In the workplace, employees confronting greater diversity of viewpoints than in their news and social media consumption may respond to disagreement with incivility. This is because people tend to dehumanize those with different political viewpoints, and to some extent, results from a perception that opposing views pose a threat (Crawford & Pilanski, 2014).

Employees are increasingly pressuring businesses to take political action, reflecting a combination of their feelings of powerlessness as individuals and their beliefs that employees and employers should have concordant values. Research indicates greater political bias in workplaces than in the past (Smith, 2022). The massive presence of political dispute at work is quite a new development that organizations must learn how to handle it because there are no legal protections for political beliefs; considering political views in hiring, promotion, or assignment to projects and so forth is generally legal in the US (with some variation by state) but is it ethical or advisable?

There is little historical research on political conflict in the workplace, in part because politics used to be a taboo subject at work (Swigert et al., 2020). Some existing research is applicable, however, and fresher, more direct research on workplace polarization is rapidly becoming available.

- Ideas to Apply

- Areas of Research

- Theories

- Definitions

- Why polarization has increased and is gaining in strength

- Individual Psychology of workplace polarization

- Influence of organizational and interpersonal factors

- The effects of political polarization in the workplace

- Managing Workplace Polarization

- Emphasize and affirm political differences as a protected class of diversity

- Recommendations for Future Research

- Recommended Reading

Ideas to Apply (based on research covered below)

- Unprecedented political polarization in workplaces is creating problems for which organizations are unprepared, and for which research is lacking.

- Multiple negative impacts of political polarization at work include mistreatment of employees, problematic effects on company culture, and reduced performance.

- Individual psychology can explain the human tendency to embrace polarization and mistreat political opponents.

- Group and organizational psychology further explain how political polarization functions in the workplace.

- Political polarization is linked to activism by corporations and employees.

- Organizations can address political polarization through policies and procedures and workplace culture, as well as by making decisions regarding any institutional orientation toward political activism.

- The previous absence of politics in the workplace, relative to today, has left organizations with little research on which to base solutions.

- Because even individuals with politically polar opposite stances share similar underlying mechanisms of belief formation, standardized interventions can have broad success.

- Individual differences in biology, values, emotions, and personality are important considerations when it comes to understanding and modifying workplace behavior.

- It has been suggested that political diversity should be protected like other forms of diversity, in part because political views are at least partially predetermined.

- An organization must ultimately make values-based decisions about how it will (or will not) participate in political speech at work and in activism in general.

Areas of Research

In an effort to understand workplace polarization, reviewed topics include the reasons for growing political polarization, how polarization affects the working environment, the individual and group psychology of polarization, and remedies for problems of polarization at work.

Theories

Cognitive Dissonance Theory. CDT provides insight into how employees manage conflict between their political beliefs and the prevailing attitudes in their workplace. The theory suggests that individuals experience discomfort when they hold two or more contradictory beliefs, ideas, or values simultaneously (Harmon-Jones & Mills, 2019; Festinger, 1957). To reduce this discomfort, they may change their attitudes or beliefs, seek out consonant information, or downplay the importance of the conflict.

Confirmation Bias Theory: Confirmation bias is a psychological phenomenon whereby individuals favor information that confirms their existing beliefs while ignoring or discrediting information that contradicts them (Van der Linden & Roozenbeek, 2020; Nickerson, 1998). This can fuel political polarization, as employees may be more inclined to accept information that aligns with their political beliefs and dismiss dissenting views (belief disconfirmation paradigm; Cancino-Montecinos et al., 2020).

Conservation of Resources Theory. Individuals aim to maintain, safeguard, and enhance their psychological resources, finding the potential or actual depletion of these valued assets to be a threat (Gui et al., 2022; Hobfoll, 1989). In times of stress these resources are depleted, and additional efforts are enacted to protect resources that remain.

Fundamental Attribution Error Theory: People tend to overemphasize personality-based explanations and underemphasize situational influences for behavior observed in others, while doing the reverse for their own behavior (Ross, 2018). The concept has been revised to isolate an illusion of superior personal objectivity as the primary source of these errors.

Group Polarization Theory: Group discussion tends to polarize group members’ views, making the average view of group members more extreme than it was before the discussion (Isenberg, 1986). This theory may be relevant to understanding how group political discussions can exacerbate political polarization.

In-Group/Out-Group Bias (Tribalism): Individuals naturally favor those they perceive to be part of their “in-group” and may discriminate against those in the “out-group” (Billig & Tajfel, 1973). This can become apparent in the workplace when political affiliations form the basis of in-groups and out-groups, leading to bias and potential conflict.

Intergroup Contact Theory: Contact among diverse groups—under appropriate conditions—can reduce prejudice and enhance mutual understanding (Allport, 1954). In the context of a politically polarized workplace, fostering interaction and dialogue among employees with disparate political beliefs could potentially reduce animosity and promote understanding.

Job Characteristics Theory. Proposed by Hackman and Oldham (1976), JCT postulates that five job characteristics contribute to higher levels of job satisfaction, motivation, and performance: skill variety, task identity, task significance, autonomy, and feedback. Autonomy and feedback in particular may be threatened in polarized climates.

Leader Cultural Intelligence Theory. Social integration of diverse people can be achieved through inclusion and social integration. By modeling openness, building empathy, and seeking understanding of diverse perspectives, psychological safety can be improved for everyone (Fujimoto & Presbitero, 2022). Applied to workplace polarization, leaders with high Cultural Intelligence (CQ) may be more effective at managing political diversity.

Leader-Member Exchange Theory. Leaders can establish enduring, strong, trusting, and respectful relationships with employees (Dansereau, Graen, & Haga, 1975; Stinglhamber et al., 2021). This happens in three steps: role-taking, role-making, and routinization. Leaders’ relationships and their handling of political diversity can significantly impact the degree of political polarization within the team.

Motivated Reasoning Theory. People believe what they want to believe, or at least they do when they can construct what they perceive as reasonable justifications (Kunda, 1990). As a result, people search for those justifications instead of approaching topics objectively. Personal emotions and the desire to confirm existing beliefs are common drivers of motivated reasoning.

Organizational Culture Theory. Organizations have distinctive cultures shaped by their history, leadership, values, and practices (Schein, 1985; Knoll et al., 2021). Political polarization in the workplace may be influenced by an organization’s culture and the norms it establishes around political discussions and behaviors.

Organizational Justice Theory. Perceptions of fairness in the workplace can be divided into distributive justice (fairness of outcomes), procedural justice (fairness of processes that lead to outcomes), and interactional justice (fairness in interpersonal interactions) (Greenberg, 1987). Perceptions of fairness around how political discussions and conflicts are managed could influence the degree of political polarization within a workplace.

Organizational Silence Theory. Employees often withhold their opinions, ideas, or concerns due to assorted reasons such as fear of negative consequences or perceived futility (Morrison & Milliken, 2000). In the context of political polarization, organizational silence can exacerbate polarization as it prevents open dialogue and understanding among different political viewpoints.

Self-Categorization Theory. Individuals self-categorize in different ways depending on the social context, which can lead to an enhancement of similarities within groups and differences between groups (Turner et al., 1987). These perceived differences can exacerbate political polarization and intergroup conflicts at work.

Self-determination Theory: There is a meaningful psychological difference between being autonomous and being controlled. This theory is adapted to tackle issues such as “the effects of social environments on intrinsic motivation; the development of autonomous extrinsic motivation and self-regulation through internalization and integration; individual differences in general motivational orientations; the functioning of fundamental universal psychological needs that are essential for growth, integrity, and wellness; and the effects of different goal contents on well-being and performance” (Deci & Ryan, 2012).

Social Exchange Theory: Interpersonal relationships as transactional, whereby individuals try to maximize a cost-benefit balance. Through experience, observation, and anticipation, each person tries to engage in the behavior and relationships that will bring the most rewards and fewest costs (Ahmad et al., 2023; Cook et al., 2013).

Social Identity Theory. Individuals derive self-esteem from social group memberships, highlighting the way people classify themselves and others into in-groups and out-groups (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). In a polarized political climate, employees may identify more strongly with their political group, leading to an intensification of in-group favoritism and out-group discrimination.

Social Influence Theory. People are motivated to create accurate perceptions of reality and to react in a manner consistent with those perceptions. They also seek to build and maintain meaningful social relationships and a favorable self-concept. These motivations indirectly—and without awareness—may determine levels of conformity in response to social influence (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004).

Spiral of Silence Theory. People are less likely to express opinions for fear of isolation if they believe they are in the minority (Noelle-Neumann, 1974). This can be relevant in understanding how a dominant political culture in a workplace might silence differing opinions, contributing to an atmosphere of polarization.

System Justification Theory: People are motivated to defend and justify the status quo, even when it may be disadvantageous to certain groups (Jost & Banaji, 1994). In a workplace setting, this could mean employees aligning with political beliefs that uphold the existing system, potentially polarizing them against those who advocate for change.

Theory of Recognition. A constant struggle for recognition is at the heart of social interactions. In Honneth’s view, social conflicts and struggles for justice can often be traced to a lack of recognition. Disrespect or injustice leads to social conflict or struggle, while mutual recognition begets social justice and personal self-realization.(Honneth, 1997; Bailey et al., 2019)

Uncertainty management theory (UMT): Uncertainty creates an aversive state in which people either try to resolve the uncertainty or begin to create buffers for themselves against potential threats. Uncertainty can be a desirable state in some situations, such as hiding wrongdoing. In the workplace, UMT predicts that individuals will seek authority figures and try to craft a safer working environment as ways of dealing with uncertainty (Hogg & Belavadi, 2017; Lind & van den Bos, 2002; Tangirala & Alge, 2006).

Workplace Incivility Theory. Introduced by Andersson and Pearson (1999), it posits that low-intensity deviant behavior with ambiguous intent to harm the target contributes to a hostile work environment. Political polarization can exacerbate or become a form of workplace incivility if political disagreements are not managed respectfully.

Definitions

Cognitive Dissonance. Cognitive dissonance describes the psychological discomfort experienced by an individual who holds two or more inconsistent beliefs or attitudes (Festinger, 1957). The concept is relevant to workplace political polarization as it influences how employees react to conflicting political views.

Confirmation Bias. Confirmation bias refers to the tendency of individuals to search for and interpret information in a way that confirms their preexisting beliefs (Nickerson, 1998). This can exacerbate political polarization as people seek only information that supports their positions.

Group polarization. Group polarization occurs when individuals with similar political or ideological views interact within a group setting, resulting in a collective stance more extreme than each might initially have held (Myers & Lamm, 1976).

Groupthink. Groupthink is a mode of thinking that occurs when a group’s desire for harmony and conformity leads to irrational decision-making processes (Janis, 1972). Political polarization can result from groupthink as members adhere to ideology to get along.

Ingroup Bias/Favoritism. The preference for members of one’s own group over others may lead to workplace conflicts when opposing groups display strong polarization (Tajfel, Billig, Bundy, & Flament, 1971).

Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB). Behavior that contributes indirectly to the organization through the maintenance of its social system (LePine et al., 2002).

Organizational commitment. Organizational commitment—an employee’s attachment to, or identification with, their organization—can predict retention and job performance (Meyer & Allen, 1991). Employees with high organizational commitment show increased loyalty and engagement.

Organizational culture. Organizational culture refers to the shared values, norms, and practices within a workplace that shape employee behavior and decision-making (Schein, 1990). It can significantly impact organizational adaptation and performance.

Political Skill. The ability to understand and influence people for personal gain or to further objectives. Those with higher political skill adjust behavior to social cues, perceive what others want and need, and can predict the reactions of others (Cullen et al., 2014; Karatepe et al., 2019).

Psychological Capital. A psychological resource or positive motivational state that facilitates successful responses to, and resistance to, psychological distress. It is typically described as having four components: hope, resilience, self-efficacy, and optimism (Al-Zyoud & Mert, 2019).

Psychological Safety. A shared belief that individuals are safe to speak their mind and take interpersonal risks; a confidence or sense that speaking up will not lead to rejection, embarrassment, or punishment within an organization or group (O’Donovan & McAuliffe, 2020; Rego et al., 2020).

Why polarization has increased and is gaining in strength

The story of how we got here is multilevel and reflects how individual psychology operates under the pressures of social and group forces and in the context of major upheavals in society and technology.

The polarization emerging at workplaces is just a visible and troubling symptom of larger shifts in culture and modern life. When identifying the drivers of polarization, Coleman (2021) suggests that three stories emerge:

- The People Story: Humans are highly emotional, esteem-thirsty, cognitive misers;

- The Group Story: Humans form group preferences quickly, and groups tend toward conformity and extremity;

- And the Societal Story: Differences in societal norms and structures matter, with hostilities accumulating over time.

Following this structure, we can begin with the psychology of the individual and then expand to group and societal factors in political polarization.

The growth of polarization can also be viewed as happening from two directions (Jost, 2017): bottom-up (personal, dispositional) and top-down (environmental and contextual). Bottom-up refers to an individual’s personal character and how who they grow into what they believe, such as an inherently empathetic person gravitating toward prosocial solutions to problems. Top-down refers to the experiences and context that act upon the formation and modification of beliefs. The effects of travel and new experiences are common examples of a top-down influence on beliefs.

There are both consistent and inconsistent bottom-up forces. For example, everyone tends to be a cognitive miser (looking to arrive at decisions without spending too much mental effort), while certain dispositions toward empathy and anger may vary considerably among individuals according to their genetics/biology. Polarization is probably growing so rapidly because top-down forces are acting in a way that amplifies bottom-up factors into vastly disparate viewpoints and political positions.

An example of a top-down influence is news. People are not particularly good at detecting fake news, despite believing that they can distinguish real from fake news (Edkins, 2016). This misinformation may affect organizations whose employees believe in things that aren’t real. While the existence of fake news is beyond our control, it is possible to understand how people interpret news and how that news enters the workplace.

Individual Psychology of workplace polarization

Solving polarization in the workplace begins with understanding how humans tend to process information and how beliefs are formed. This includes how we determine what is true, what we value, and how we process information. There are also natural human tendencies in how we integrate new information differently, depending on whether we agree or disagree with it. A further important consideration is the extent to which we have a choice in what we think or if it is determined by genetics and the environment.

The way people think is somewhat predetermined

The way we think is increasingly viewed as not just our choices, or a result of our environment, but fixed to some extent by genetics and other factors. Alford et al. (2005) stated that “genetics plays an important role in shaping political attitudes and ideologies but a more modest role in forming party identification”; additional research confirms that genetics may determine political thinking (Twito & Knafo-Noam, 2020; Smith et al., 2012). It has been estimated, through research including studies of twins, that 40 percent of political orientation is heritable (Dawes & Weinschenk, 2020).

Every part of political thought formation seems to be heritable, from basic attitudes and interest in politics to actual voting decisions. One’s family interactions, as well as other socializing forces in life, are not enough to overwhelm the heritability of political orientation. Bell and colleagues (2009) wrote:

This may partially explain why people at one end of the political continuum react with such incredulity when encountering those at the opposite end, often thinking that their political opposites are stupid or crazy—or worse, when they may simply have different political dispositions. Similarly, these findings may help to explain why it is difficult to politically “convert” a person from a right-wing to a left-wing orientation, or vice versa, even after prolonged, reasoned argumentation.

It may be reasonable to think of a person’s politics in the same way we think of their race or sex—as beyond their control; this would render it unfair to mistreat someone based upon their views (Miner et al., 2021). However, the line is unclear. We routinely discriminate based on natural amounts of certain abilities and areas of intelligence, especially when they pertain to a job. Because political beliefs are rarely job relevant, they may be better categorized as unfair discrimination when used in the course of making employment or workplace decisions. However, as no legal guidelines are in place, any decision is an ethical one that falls to each organization to judge with regard to their values and goals.

People have tendencies toward polarized, flawed thinking

Human beings are most comfortable in like-minded bubbles. There is roughly equal bipartisan avoidance of differing opinions. This tendency is so strong that many will forgo the opportunity to earn a cash prize in order to avoid hearing the other side of an argument (Frimer et al., 2017; Kalmoe & Johnson, 2022; Willoughby et al., 2021). Hearing differing opinions from friends and associates can even damage relationships. Frimer and colleagues wrote that the primary reason for this avoidance is cognitive dissonance, or the uncomfortable feeling of having to challenge and/or defend beliefs. A Pew Research survey found that it is stressful and frustrating to interact with people from the party with opposing views (Van Green, 2021), confirming the problem.

Unfortunately, opinion bubbles tend to drive polarization and the misunderstanding of opposing views, especially with unbalanced information feeding into our tendency to reinforce and strengthen existing beliefs (frequently to the point that opinions become extreme). Initial attitudes impact how information is processed, leading to reinforcement of the preexisting attitude or adding similar beliefs that align. These strengthened attitudes then strongly influence information processing, fostering a reinforcing loop (Coleman, 2021).

In addition to avoiding challenges to their beliefs, people do an extremely poor job of understanding what others believe (Yudkin et al., 2019). Greater political polarization brings more negative attributions (e.g., calling them “brainwashed) about those whose views they oppose. A large survey found recently that when asked what others believe, people display a large perception gap (Perception Gap, 2023). For example, Democrats underestimated the percentage of Republicans who believe immigration can be beneficial by 33 percent; Republicans over-estimated the percentage of Democrats who support open borders by the same 33 percent.

A common flaw in both left and right is apparent here, with progressive activists and devoted conservatives about equally inaccurate in their estimates—and much less accurate than people in the political center. Politically disengaged respondents actually put forth the most accurate estimates, possibly because they take in less media that distort perceptions. In general, the more someone followed the news, the larger the gap in their perception compared to reality. For Democrats (but not Republicans), those with more education tended to have a larger perception gap and less diversity of opinion among friends, furthering the notion that information bubbles and distorted views go hand in hand.

These political differences run much deeper than dislike and avoidance. Political enemies are actually viewed as somewhat less human (Simmons, 2022). Using the classic “ascent of man” image, participants in a Stanford study rated their dehumanization of the opposing side by selecting how evolved (or not) they were, rating opponents less human or less evolved than themselves and other like-minded people. This dehumanization was partially reciprocal; participants rated others as more evolved when they believed the others did not dehumanize them, notwithstanding differences. The Stanford researchers noted the short distance from dehumanization to violence; presumably, there is an even shorter distance to workplace mistreatment. The process of dehumanization also justified undemocratic activity on both sides of the aisle, an indication that people suspend customary rules of behavior when they deem opponents less than fully human.

People frequently believe misinformation and conspiracy theories

When thinking about why and how people believe in misinformation and conspiracies, it’s important to view this as a tendency to believe what is different. On a sliding scale, someone likely to believe in inaccurate information is also likelier to subscribe to the truth when the correct answer is unusual or seemingly outlandish. In other words, their judgments will entail more false positives (e.g., believing in the Loch Ness Monster, which does not exist), but also fewer false negatives (e.g., disbelieving the Watergate conspiracy, which was true).

The sharing of false news stories is a bipartisan problem. What drives it does not seem to be anything specific about people as much as it is the result of seeking confirmatory information and where that information is to be found (Osumundsen, Peterson, Bor, 2021). This is known as motivated reasoning (Kunda, 1990): wanting to believe something because of how it makes us feel or fits comfortably with our existing views. If a belief runs counter to the narrative of mainstream news outlets, a person seeking such information is more likely to find it from unreliable sources. (Mainstream news is not always reliable, but it’s more so than conspiracy blogs.) At this point, an individual’s skill at determining what is real comes into play; since most people are poor judges who are already motivated to believe the information is real, they are likely to share the information, believing it to be true.

While conspiracy theories may be of greater concern than garden-variety misinformation, there are problems in distinguishing misinformation from a conspiracy theory. When conducting the research for this page, I found that studies in the literature referenced “COVID-19 origin” conspiracy theories as examples, specifically defining the lab leak theory as misinformation/conspiracy (e.g., Stasielowicz, 2022). This origin story has come to appear to be plausible, if not provably correct (House Oversight Committee, 2023). It is no longer a fringe view. Research into this particular “conspiracy” was actually analyzing people who may have gotten it right. This illustrates how difficult it is to know what human tendencies should be celebrated and which suppressed. In research on misinformation and conspiracies, there is also the problem of either focusing on conspiracies that are almost certainly false (flat earth, QAnon) or more plausible ones (Trump colluding with Russia, election fraud). The former will result in confident results concerning how or why people come to erroneous conclusions, but they will apply only to an extreme subset of people who believe the most outlandish claims; the latter is more generalizable to ordinary people, yet it may not always represent incorrect information/theories.

There is also bias in misinformation research. This reflects the views of the researchers, who will inevitably have the ability to see certain types of misinformation for what they are while not recognizing types of information they are inclined to believe—which might be wrong. A conservative researcher may seek (and probably find) the weaknesses of cognitive processes in liberals, while a liberal one will better detect the faults in conservative thinking. Confirming such intuitions is a valid scientific inquiry, but it is biased and incomplete.

There is some evidence regarding the importance of individual differences in the tendency to believe conspiracy theories, including mental disorders, lower cognitive ability, and less education (Furnham & Grover, 2022). Conspiracy believers tend to be lower in age, likelier to be members of racial minorities, and greater consumers of social media (Nan et al., 2022).

Despite efforts to relate the holding of conspiratorial beliefs to such personality traits as openness and agreeableness, widespread support for these ideas has not been consistent (e.g., Goreis & Voracek, 2019). Goreis and Voracek also stated that more work is needed on theoretical frameworks to explain conspiracy beliefs and that current research is too homogeneous in design and methodology.

Instead of personality, it seems that conspiracy thinking is more related to an adherent’s feeling of powerlessness, need for answers to questions (cognitive need for closure), quest for belonging, and wish to confirm existing beliefs (Arellano, 2023; Nera, 2020; Marchlewska, Cichocka & Kossowska, 2018; Papaioannou et al., 2023; Wheeler, 2021). A common example of concordance with existing beliefs is found regarding flat earth theorists in the U.S., who are overwhelmingly of the Christian faith, probably because a flat earth would conform to biblical descriptions (Fernbach & Bogard, 2023). This is not to suggest that people of this belief system are more susceptible to conspiracies, only that they are more susceptible to the flat earth theory because it conforms to their existing belief system. Additional examples include those who distrust corporations being likelier to believe in GMO conspiracies and the general human tendency to believe conspiracy theories involving political opponents they strongly dislike.

As soon as someone comes to believe in a conspiracy, they belong to a social group. This group has been assessed to “know the truth.” An answer is more comforting than unanswered questions. This leads the new believer to feel more intelligent, unique, and accomplished without having to make the usual efforts to distinguish themself. This process is self-reinforcing. It fosters a new worldview around which confirmation bias and information bubbles are constructed, and this maintains or furthers the believer’s drift away from reality.

Because the way people think is highly consistent—tending toward use of the same heuristics and processes—the result is homogeneity that underlies polarization regardless of political direction (left, right, authoritarian, laissez-faire). Left and right feel like opposites, but they are mirror images in that the “other side” is seen as more extreme, misinformed, and less mentally capable. Moreover, everyone tends to want to continue believing what they have believed in the past, what their social circle believes, and so on. Even our differences of opinion, to the extent that they are hard-wired and we did not choose them, show how much we resemble opponents, who were shaped by the same forces.

Influence of organizational and interpersonal factors

Workplaces are stressful environments in which responsibilities and social interactions take a toll on personal resources. In line with Conservation of Resources theory, political friction may provide an additional source of stress that consumes resources (He et al., 2019). Ordinary work stresses may leave people less capable of resisting political incivility while it simultaneously threatens employee productivity and mental health. As for resources, the design of jobs and systems in a workplace (e.g., Job Demands Resources Theory) influences whether there is additional capacity for politics and whether politics could interfere with the successful completion of tasks.

The workplace’s interaction with political polarization can also be viewed through the lens of counterproductive work behavior. This tends to be promoted by organizational constraint, a climate of aggressiveness, and breach of psychological contract, mitigated by organizational support and ethical climate (Liao et al., 2021). Following this logic, it is expected that such behavior as incivility and politically based maltreatment of all kinds are more of a problem in less supportive, more challenging work cultures.

Yet another conceptualization of workplace political polarization is the idea of attractors (Coleman, 2021). These are patterns underlying something that seems to resist change for a long time; here, that thing is political polarization. More important, the theory of attractors posits that this pattern—polarization—is not the result of any single factor but results from a complex network of elements that interact with, and feed off, one another. These interconnected elements consistently can draw us into a set of patterns and can be exceedingly difficult to change.

The complex web of elements that underlie attractors is split into three reinforcing phenomena: vicious cycles, vicious cyclones, and superstorms of polarization. A vicious cycle come about when, through processes like confirmation bias, one ends up in reinforcing feedback loops that exacerbate and further polarize thoughts. When these vicious cycles are combined with other feedback cycles such as in-group socialization, homogenous social networks, and internet thought bubbles, a vicious cyclone is formed—essentially a confluence of factors that distort the flow and processing of information. Finally, when “economic, political, and psychological factors at the individual, community, national, and international levels” are introduced, with each affecting these vicious cyclones, a superstorm of polarization is created. Elements at all levels of information processing, sharing, and dissemination combine, interact, and reinforce one another in such a way that the attractors born from them become extremely complex.

Attractors are extraordinarily change-resistant for two main reasons. First, as mentioned above, they are created by an intricate network of reinforcing elements. No single change among them will have much effect on the entire network comprising the attractor. As Coleman (2021) describes it, “we are rarely confronting an isolated issue or a disagreement over facts”; rather, “we are facing off against everything that underlies why the issue matters so much in the first place.” The second reason attractors so effectively resist change is that they often satisfy two basic psychological motives: They give us a coherent understanding of a conflict, and they provide a stable platform for action. Attractors are low-energy states, which is why we can so easily fall into their patterns. Given the sheer complexity and nuances of today’s issues, attractors provide much wanted, albeit simplified, clarity. People who are involved in politics and social movements want to “mobilize the troops,” so to speak. When issues are simplified into good-vs.-bad and us-vs.-them dichotomies, people are more readily moved to act. The true complexity of most issues would make it much more difficult to do so. These attractors therefore make action-directed thought a much easier process for those involved; they become the path of least resistance. People and organizations are currently experiencing vicious cyclones that endanger productivity and civility. Biases and bubbles have driven polarization to new heights. And such events as elections, shootings, and war are the type of catalysts that can amplify cyclones into superstorms.

Group dynamics are an inherent aspect of organizations. They manifest in workplace conversations about politics when employees engage in debates along polarized lines. In some cases, individuals feel pressure to conform to the majority view within their group, or face exclusion (Levi, 2017). Group dynamics such as group polarization, groupthink, and the bandwagon effect can lead to the suppression of dissenting opinions and contribute to misunderstandings or misconceptions about opposing views. When these dynamics are present, it is important to carefully consider their impact on the group and the workplace.

Group polarization occurs when deliberation among like-minded individuals leads to a strengthening of their initial position, resulting in more extreme viewpoints (Myers & Lamm, 1976). When applied to workplace politics, this can cause employees to become increasingly entrenched in their beliefs and less open to alternative perspectives. Such entrenchment exacerbates political polarization and makes productive discussions about politics more challenging.

Groupthink, on the other hand, denotes a decision-making process wherein group members strive for consensus at the expense of critical evaluation (Janis, 1972). In workplace political conversations, this pressure for conformity may lead employees to suppress dissenting opinions or withhold information that contradicts the majority view. This phenomenon can further magnify political polarization and contribute to an environment in which diverse perspectives are discouraged.

The bandwagon effect refers to the tendency of individuals to adopt certain behavior or attitudes due to their popularity or perceived popularity among peers (Bindra et al., 2022; Leibenstein, 1950). In the context of political discussions at work, employees may feel compelled to express or support specific views because they believe others around them hold those opinions.

These group dynamics have profound implications for how we think about and respond to the world around us. They can be mitigated with the right tools and techniques. However, the first step is to understand how these dynamics work and how to recognize them.

Incivility is a social process. Research has shown that when someone observes incivility, their own productivity and creativity are likely to suffer (Porath & Erez, 2009). When in the context of competing for resources— particularly relevant for competitive organizations—there is less disruption of the observer’s ability to continue work. However, highly competitive environments are also those where incivility is likely to spread more easily (to create advantages). Whether it’s harmful or a sign of a bad culture, incivility at work is rarely just a story of isolated incidents.

It comes as no surprise that the context in which incivility takes place also matters. For example, those dissatisfied with their job situation are much more likely to do a worse job after experiencing incivility (De Clercq et al., 2019). Incivility is less damaging to employees who are otherwise content. In the context of political polarization, incoming stress and incivility from factors like a stressful election will wield more impact on organizations that are already struggling with employee job satisfaction.

One part of comprehending the impact of regional/national politics on the workplace entails, rather ironically, gaining a greater understanding of workplace politics. Not to be confused, one is about elections and politics at the city/state/federal level while the second addresses a workplace with a lot of self-interested positioning and politicking (Jha & Sud, 2021). While technically unrelated, workplace politicking is a major factor in catalyzing incivility and external politics will almost certainly feed into these internal politics. Someone who perceives themself an outsider in terms of national politics, for example, may also suffer from workplace politics that limit their ability to succeed or work comfortably.

Zeitgeist and Technology

In addition to who we are and the people we interact with, where we are (both physically and chronologically) is important. Some examples include an increasingly partisan news media, social media, and political elites (Wilson et al., 2020).

The information people get is increasingly curated, selected, and sourced from like-minded social connections. From these flow such polarizing elements as caricatures of opponents, incorrect attributions for the actions of others, and extreme ideas.

News media have been increasingly moving toward articulating partisan politics, an approach leading to more views and revenue than unbiased approaches would bring (Fletcher, 2022). These media are welcomed into information bubbles because they report in a manner agreeable to the partisans they serve; they will continue to deliver what their audience wants to hear. There is little reason for them to service opposing views or middle-of-the road views because few people with moderate views would consider patronizing these outlets.

Social media, an ideal place for creating and maintaining an information bubble, rewards the loudest, most polarizing voices. Through both self-curation (following, blocking) and algorithms (recommendations, visibility of posts), many people have in their social media constructed not only an echo chamber but an amplification and polarization chamber: A single worldview is presented, rewarded, and rarely challenged.

Wilson et al. (2020) attribute some blame to political elites as well. Everyone can see the outsized and controversial influence that elite people and groups wield. There is evidence that elites are themselves becoming more polarized, and they often find it rewarding to stir dislike, anger, and even disgust toward opposition figures and groups. Those with weak arguments in particular may turn to tactics that demonize the opposition. Wilson et al. summarized it this way:

We contend political elites have become both more polarized themselves and more incentivized to stoke polarization among voters, that partisan media selectively portray political opponents in caricatured and polarizing ways, and that via social media people actively contribute to shaping a political landscape that disproportionately reinforces and amplifies extremity and outrage (p. 7).

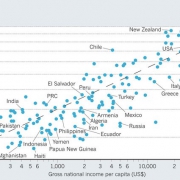

Even geography seems to influence politics and polarization considerably (McCarty et al., 2019; Scala & Johnson, 2017). One’s physical location is likely to influence initial beliefs (e.g., formative childhood experiences, culture) as well as providing a nearly inescapable source of information that isn’t filtered through the media or technology.

It isn’t the focus of this research page to thoroughly explore these many external factors, but instead to briefly summarize them because they are forces that may drive political polarization at work. Thinking about how these forces could be mitigated at the individual and organizational level is important for overall efforts to keep workplaces sane and civil.

The effects of political polarization in the workplace

When one employee perceives another as a member of an out-group or as an enemy of sorts, several counterproductive outcomes are likely to result: ostracism (ignoring or excluding), incivility (harassment, unkind speech or behavior), discrimination (different rewards/punishments based in political stances), sabotage (intentional harm to employment, career, status), and aggression/violence (harmful verbal or physical attacks).

Political views are a common seedbed for this. Take, for example, the already divided U.S. population regarding former President Donald Trump’s statements regarding race in 2017. Whatever an onlooker believed was already being affirmed by countless like-minded media and pundits. Then, when Trump commented (Cortes, 2019) on the violence in Charlottesville, Virginia, everyone continued to get an interpretation consistent with their preexisting views. The political left believed he had described white supremacists as “fine people” while his supporters maintained he had done no such thing. This could leave a Republican in a workplace seeming to be a white supremacist in the view of some coworkers. But say the worker in question did not hold racist views and genuinely did not believe themself to be following someone who did. Both viewpoints are comprehensible. Nobody expects to have to tolerate a white supremacist at work; nor can anyone expect a maligned staffer to feel comfortable with coworkers believing such things about them. The same risks exist for left-leaning individuals at work as well. Joe Biden has frequently been attacked as racist (e.g., Dupuy, 2020), but his supporters typically do not believe he is racist, and most presumably would not support him if they believed he were. People on both sides of the aisle are frequently mislabeled as being more extreme (e.g., communist, fascist) than their actual positions would imply, due to their support of a particular candidate or party.

Today’s political opponents are, more than in past years, viewed not just as having the wrong opinions but as bad people or people with bad intentions. On such issues as health care, the overwhelming majority support what they believe will lead to the best access and quality; nonetheless, some are demonized as wanting to ruin, take away, or deny care by those who prefer a different system.

Because our politics have become part of our identities, this typically leads to the same type of in-group preference and poorer treatment of outgroups, partially explaining why mistreatment occurs (Swigart et al., 2020). Outgroups are stereotyped and diminished, which at work can mean exposure to negative assumptions about competence, reliability, or how much a person deserves opportunities and rewards.

Authoritarianism within the organization—its structure and leadership—can also pose problems. Authoritarian leadership style (also known as paternal leadership) is “negatively related to workplace outcomes such as team interaction, employees’ organizational commitment, task performance, helping, and vocalization behavior,” and may even limit support for change within an organization (Du et al., 2020). Authoritarian leadership “contributes to workplace mistreatment by drawing sharper boundaries between groups of employees” (Leiter, 2013). Typically, the problem of authoritarianism has been discussed in terms of race and sex and how it deepens those divides. However, it also applies to political differences. Authoritarian leadership can create a workplace in which employees are afraid to speak up and whose managers and supervisors are afraid to take a stand against a leader.

Authoritarian views inherently threaten a civil workplace because control, repression, and exclusion are what differentiate authoritarianism from other political orientations. In the same way that the authoritarian seeks to wield the power of government to control others, an organization can serve as a source of power. Political orientations are correlated with leadership styles (e.g., Nicol, 2009), though the extent of this is not known due to a dearth of research on the subject. Authoritarians come into the office primed for volatile political interactions due to tendencies toward “dogmatism, cognitive rigidity, prejudice, and lethal partisanship” (Costello et al., 2020). The left-wing authoritarian may carry into the workplace strong, group-based judgments against political conservatives, religious people, nationalists, and some ethnicities. Conversely, the right-wing authoritarian is likely to bring in equally harmful negative views about liberals/progressives, atheists, immigrants, and again, certain ethnicities. Both are likely to disrupt organizational goals as they may desire radical social changes that are not feasible, have extreme adherence to or opposition to hierarchies, and are generally intolerant of disagreement. Authoritarian leadership is related to greater risk of workplace bullying (Feijó et al., 2019). Moving to avoid authoritarianism in the workplace is an initial requirement in creating a more civil workplace.

Despite not invoking the left-right paradigm that is most controversial and recognized, preventing authoritarianism in the workplace still requires making judgments about political leanings and is not free from risks. For example, Feijó and colleagues found that excessively laissez-faire leadership can also bring a risk of bullying—perhaps inadequately prevented or punished by a lax leader—unless the work culture and policies provide protection for employees.

Nonpolitical characteristics such as social dominance orientation can offer a way to identify and avoid authoritarianism in the workplace. Social dominance orientation is a tendency to seek and maintain social dominance and is linked to authoritarianism. Leaders higher in social dominance may discriminate against certain groups when involved in making employee-selection decisions, especially when hiring for other leadership positions (Simmons & Umphress, 2015). As with other political attitudes, social dominance seems to have genetic underpinnings (Kleppestø et al., 2019), so caution is needed to avoid judgments based on what may be someone’s genetic predisposition.

Increased strain and incivility within the workforce

The level of polarization in today’s workplace is truly disruptive. It is on track to become one of the largest challenges in managing employees to work effectively together. Gartner research (2020) reported that nearly half (47 percent) of workers had their work significantly impacted by the 2020 election, and that more than one-third (36 percent) avoided talking to, or working with, other individuals because of politics.

Incivility, or “low-intensity deviant behavior with ambiguous intent to harm the target” (Di Fabio & Duradoni, 2019), is a predictable outcome of workplace political polarization. Incivility has been “shown to impact roughly 98 percent of the workforce, with half of the workforce experiencing incivility at least on a weekly basis” (Andersson & Pearson, 1999, as cited by Akella & Lewis, 2019).

Incivility may take place in three ways (Schilpzand et al., 2016): experienced (directed at oneself), witnessed (seeing someone else targeted), or instigated (being uncivil toward someone else). Most research investigates experienced incivility, with many fewer studies available on that which is witnessed or instigated.

Incivility may be, in part, an expression of human nature wherein “fight or flight” instincts lead to defending ourselves, or even attacking others, when we perceive a threat or stress. Incivility may be a way some individuals attempt to bring others down (in lieu of working hard and competing in performance) when they feel they do not compare favorably. Incivility may stem from “a communicator’s desire to exclude attitude-discrepant others” (Hopp, 2019). A person might infer incivility in a message, even when none was intended, because they are aware of—and are even scanning for—attempts to exclude or attack them.

A leading researcher in the area of workplace incivility, C. L. Porath, has stated that the impact of incivility on employees is “sneakily robbing them of resources, disrupting working memory, prompting dysfunctional thoughts and ultimately hijacking performance” (p. 264); she also confirmed that incivility is indeed communicable, as many suspected, based on observations. Its contagious nature puts teams at elevated risk due to their shared interactions and opportunities for passing on blighted behavior.

The environments in which we work are partly responsible for increased incivility. Work pressure activates stress responses including incivility, while digital communication, greater diversity, and misunderstandings about what is appropriate at work can all contribute. Diversity, while typically viewed as positive, is a contributing factor to differences, misunderstandings, and suspicions of race-based entitlement at work that often lead to increased incivility (Akella & Lewis, 2019; Blau & Andersson, 2011). If diversity drives incivility, politics certainly can, too. After all, diversity is not a matter of choice, and being uncivil on the basis of race is generally frowned upon.

People identify groups and then treat those in the group they belong to better than they do those of another group. This is done unconsciously. It does not rely on bigotry or prejudice, and it is difficult to stop. The effect also tends to be stronger when one group is dominant—for example, incivility toward females in male-dominated environments. This means that workplaces with a lot of employees on one side of the political aisle are highly likely to generate incivility toward those with views on the opposing side.

When any form of politically motivated mistreatment occurs, the organization suffers because these problems typically negatively affect productivity, employee satisfaction/burnout/turnover, and company reputation, too; they can also open the organization up to legal repercussions (Akella & Lewis, 2019; Grantham, 2019; Liu et al., 2020). While there is no federal law against an employer using politics to discriminate, certain states offer limited protections (Mateo-Harris, 2016). Even when nothing illegal has occurred, contentious workplaces undermine trust.

A dearth of psychological safety is a major mechanism through which incivility leads to worse outcomes. The sharing of ideas, or taking of any action that makes one more visible, can be stifled by the perception of low levels of psychological safety. When people feel safe, they work more openly, with less distraction and without fear of reprisal. The threat to safety cannot be thought of simply as someone being bullied or otherwise overtly mistreated. It means having the security one seeks at work undermined in any way. In fact, most incivility is experienced as illegitimate demands (Semmer & Schallberger 1996) that require time and energy to manage along with legitimate demands, potentially making the job untenable. Safety is undermined as the employee fears not performing well enough, or that performing at expected levels will require unreasonable total effort. Given that incivility can be contagious, it can occasion a less supportive workplace that spirals out of control (incivility spiral; Pearson, Andersson & Porath, 2005).

When experiencing incivility, employees tend to participate less in Organizational Citizenship Behaviors. If their ability to navigate the incivility (e.g., skill in politicking) is low, they are likelier to leave the organization than stay and fight (Moon & Morais, 2022). Employees are likely to display less initiative when subjected to incivility (Gui et al., 2022). Consistent with conservation of resource theory, incivility translates to less initiative when accompanied by emotional exhaustion.

Incivility reduces productivity (of both targets and observers) by impairing information processing, attention, resource sharing, and creativity (Porath & Erez, 2009; Porath et al., 2015). Incivility also tends to flow downward from individuals with higher power in organizations. Younger employees tend to be less civil toward older employees than the reverse, while men are more likely to be uncivil and women more likely to be targets. Incivility can exist in a relatively constant state or spiral into greater intensity and frequency. It multiplies through an organization via escalation, word of mouth, and displacement (e.g., retaliation toward someone other than the perpetrator; Pearson et al., 2000).

Political division and ostracism

Divides among employees and their factions/alliances are defined in part by political beliefs. This can serve as a justification for keeping politics out of the office, but in most cases co-workers will know one another’s politics to some extent, no matter what the organization’s rules state. For many, hiding a part of themselves is not comfortable. And there is much more room for assumptions (e.g., someone to the left is deemed a socialist when in fact they are a liberal Democrat) when politics are known but not discussed.

Ostracism is one reaction to perceived political differences. It means leaving someone out of groups, avoiding contact with them, or otherwise excluding them. A recent study found that 36 percent of people have avoided contact with someone at work because of political views (Gartner, 2020). This can manifest as physical, social, or cyber ostracism (Harvey et al., 2018). Whether left out of lunch, an important email chain, or even a promotion, excluding someone has negative impacts on the target, the ostracizer, and even observers. Further, it is “more damaging to the organization as those negative outcomes work their way through the organization creating job tension, emotional exhaustion, and a depressed mood at work” (Harvey et al., 2018, p. 9). Ostracism can even contribute to groupthink, as members of a group are likely to conform out of fear that they will be next to be ostracized.

Even when nobody is overtly ostracized, viewing the diversity of others positively can improve the functioning of work teams (Homan et al., 2007). Extending this finding to political diversity, teams would be expected to function worse when team members view political diversity negatively than they would if they held a more open minded or positive view.

Managing Workplace Polarization

Research on how to deal with polarization at work is rapidly being published due to extreme need for it. Most advice focuses on how to manage day-to-day political conflict. Beyond ordinary disagreements, there is also the problem of “trolls in the cafeteria” (Hirsch, 2018), which highlights the need for clear policies and responses to more extreme political views or to those who intend to be disruptive.

As previously mentioned, the polarization profile is rather similar in each individual, even if it leads people to vastly different views. That being the case, there are potential solutions that apply broadly.

Systems and policies

Being proactive in organizational policies and systems is necessary to stave off incivility and performance deficits that arise from political polarization. Without such an approach, the culture will be haphazardly determined by incoming personalities, leading to uncontrolled drift over time. Desired changes must be keenly intended in the face of existing cultural momentum. Clarity is particularly important. Ambiguity regarding what is considered appropriate collegial behavior has been associated with greater incivility (Aquino & Thau, 2009; Agervold & Mikkelsen 2004).

Mary Baker (2020) at Gartner provided guidance on how to determine the correct policies, emphasizing use of the organization’s existing culture as a guide going forward (unless the current culture is critically troubled). The impact of political conversation in the workplace will vary greatly from one organization to another; accordingly, the policies that are most effective are unlikely to be applied uniformly across organizations and their varied cultures. One company may do best by mostly prohibiting political conversations; another may find that encouraging and participating in political conversations serves it well. Companies should consider which types of political expression will have an impact—and how. This should make it easier to sort out what should be allowed from that likely to disrupt. Baker also noted that “Gartner’s Election 2020 Survey found that at organizations with political expression policies, over 75 percent of employees agree with these policies.” This indicates that official policies on the topic are generally not unwelcome to staff.

Psychologist Kathi Miner and her colleagues at Texas A&M (2021) suggested that organizations codify protection of political identities by including them in the language of policies against discrimination and in training meant to reduce discrimination. They also suggested an approach that induces civility rather than attempts to prevent incivility; the CREW (Civility, Respect, and Engagement in the Workplace; Osatuke et al., 2009) approach has long-term data supporting its effectiveness (e.g., Leiter et al., 2011).

Systems should be put in place to discourage the undermining of subordinates and additional forms of abusive supervision, rather than relying on manager training and individual behavior (Ali et al., 2022). Abusive supervision leads to incivility because of “an unfair and politically thrilling atmosphere” in which employees vie for positions in competition with each other. To tackle incivility via policy and systems, Porath recommends several remedies (Porath et al., 2015):

- Recruit and select for civility. Pass on questionable candidates in this regard, even when talented. Do the arduous work of contacting personal references and associates. Improve recruitment by using social networks of employees and professional search firms, and poise for the long term by keeping top candidates on file for longer duration in case they become available and are needed;

- Set expectations and norms for civility. Place civility explicitly in mission statements, and maintain an ongoing, visible conversation about civility that involves employees in a way that enables them to help craft what it means to be civil in the workplace;

- Do not tolerate incivility. Give clear guidance on what is to be done—and the consequences. Follow through consistently, with consequences; and

- Recognition and rewards. Recognize good behavior when it happens. Involve employees in nominating and rewarding each other. Highly visible recognition is recommended, as are tangible rewards such as money or gifts (e.g., wearables or desk items).

Should organizations go so far as to help employees think differently, even to reconsider difficult political issues? While this doesn’t seem like an institutional responsibility, an organization could certainly benefit from initiatives such as helping employees to spot fake news (van der Linden & Roozenbeek, 2020) and conspiracy theories (Douglas & Leite, 2017). This strategy is relevant for the workplace because conspiracy theorizing may lead to less committed, dissatisfied employees, and some conspiracy theories are about the workplace, management, or the employer itself. Moreover, bullying at work can render individuals likelier to embrace fake news or conspiracies (Jolley & Lantian, 2022).

Putting policies into place against political bias in employee-selection processes is also commonly recommended. This frames talent and potential as key target characteristics and keeps positions open to the largest pool of candidates by not considering their politics. Screening for more extreme views might be limiting, especially in quests for highly intelligent candidates. Research suggests that the most intelligent individuals are the most likely to diverge from the norm and to hold more extreme views on topics like economic policy (Lin & Bates, 2022). Candidates with the highest intelligence are slightly likelier to prefer socialist, anarchist, or other views that diverge from the mainstream.

There is some evidence that clarifying job roles, rather than keeping them ambiguous, may reduce the negative effects of incivility (Sguera et al., 2016). This may be because precision in roles helps make it clear that certain actions (e.g., criticism or exclusion of others) are inappropriate, or because ambiguity taxes the same resources (stress coping) as uncivil behavior does.

Finally, organizations can benefit from incorporating the management of political discussion into their broader diversity and inclusion (DEI) initiatives. Just as these initiatives aim to create an environment that respects and values race, ethnicity, gender, and other forms of diversity, they should also promote respect and inclusion for diverse political beliefs.

For a workplace to implement such changes, it would be best to focus on critical thinking that is applicable to a variety of subjects and to ensure that any training does not make certain employees feel targeted for their views. This might mean having a program reviewed by a politically diverse group of employees before it is implemented, selecting one that includes examples of fake news or conspiracy from both left and right, and committing to maintain the program over time. Above all, it is recommended to use a program that has been credibly measured for efficacy, ideally including longer-term follow-ups.

To manage employee activism, Githens (2019) recommended that a “relief valve” be added to the organization so as to provide an optimal path in addition to the customary ones of activism, silence, or exiting the organization. A relief valve allows the expression of dissent without the need to act outside the company’s acceptable channels. Employees can advocate for change within previously agreed-upon channels when those channels are clearly communicated and effective.

Employee activism is not a “problem” to be managed. It can serve as a valid moral process through which employees let the organization know when they find its business practices morally dubious (Svystunova & Girschik, 2020). When an organization listens and chooses to act more ethically with respect to material issues, walkouts and protests can be avoided. It can be important, however, to set expectations about the extent to which employees will have a voice in such matters, as well as the procedures they should follow if they want to be heard. Are the concerns of a small minority of employees going to be considered by the leadership? Is there a process for determining what most employees prefer regarding contentious issues? Finally, transparency can be useful in revealing the fiscal impact of activism-driven decisions, as well as making visible the reasons behind business decisions.

Training and Development

Many of the problems caused by political polarization have identifiable sources and mechanisms. Employees may believe in misinformation and conspiracy theories; these are troublesome to tolerate and arguably should not be accommodated. Staff members may struggle to control their reactions to others, or may lack skills at pursuing reasoned argumentation. It’s possible, too, that some individuals lack awareness of their personal issues and find it challenging to recognize and alter how they mistreat others.

If political diversity is to be treated like any other category of diversity, it makes sense to integrate training for political tolerance into existing DEI efforts. Inclusion in such programs would have the immediate effect of signaling that political diversity is to be tolerated, like other differences. Whether an organization creates a new program to address political polarization or adds the topic to existing diversity efforts, scientific diversity interventions are likely to succeed best. Scientific diversity interventions should have certain design elements (per Moss-Racusin et al., 2014):

- be grounded in current theory and empirical evidence;

- use active learning techniques so participants engage with course content;

- avoid assigning blame or responsibility to participants for current diversity issues;

- and include a plan for ongoing, rigorous evaluation of the intervention’s efficacy with diverse groups.

Scientific interventions need measurable results. Quantification of status before and after changes to knowledge, implicit biases, attitudes, and behavior (often as rated by others) is recommended. Research is unveiling specific approaches to ameliorate political polarization, and keeping up with such guidance may be the best approach.

Many workplace problems related to political polarization can be targeted for improvement via training and development programs in the workplace. When employees feel psychologically safe and have the tools/resources they need, considerable personal development can take place. With many junior staff reporting difficulty “adulting” (Golden et al., 2020), suitable training may be appreciated by employees who seek work/life balance. Conspiracy theories tend to appeal most to those who feel powerless, so making employees feel empowered in work and life may help them resist (Van Prooijen, 2018).

Training staff to think critically and to understand multiple viewpoints may act as a buffer against political polarization in an organization. While it is not the responsibility of employers to develop workers’ basic life skills, management may want to consider it, given the benefits. Heightened critical thinking may protect employees against believing misinformation and help spur more productive conversations about issues. Critical thinking—a basic business skill with many applications relevant to the workplace—typically receives little attention in business degree programs (Calma & Davies, 2021). Additional areas for potential development include how to locate quality sources and information, understand opposing viewpoints, attain mindfulness (Simonsson et al., 2022), and develop psychological flexibility.

Education or training in moral foundations (Graham, Haidt, & Nosek; 2009) may also be effective in helping employees understand more accurately, and demonize less, those with differing views. Instead of leaping to assumptions, knowing the moral foundations of a belief makes it more understandable and can reveal how good intentions can lead to that position on an issue. This approach states that each person’s value system is based in varying degree on values we all esteem to some extent (Care, Fairness, Loyalty, Authority, Purity, Liberty; MoralFoundations.org, 2023). People on the political left tend to value care and fairness above other dimensions, while those on the right value all of them more equally. So, for example, it may help to know that in discussing immigration, someone on the left might focus more on caring for less fortunate people and see fairness as extending to foreigners who deserve a life more like their own; a conservative might focus on the dimension of loyalty (whereby Americans should help each other first), or that of sanctity (believing that American culture contains something special that cultural mixing dilutes). All these explanations are more positive than what might be assumed in an argument—such base considerations as racial antipathy or an interest in importing like-minded voters to sway elections. Economic motives follow a similar pattern: Both sides want prosperity, with one focused on those with the direst needs (immigrants, asylum seekers) and the other on loyalty (descendants of Americans).

Civility may benefit from coaching or other forms of training “schools”’ (Porath et al., 2015). Coaching can help reduce incivility, and coaches can personally detect and observe sources of incivility within an organization; discordant themes will inevitably crop up in sessions with employees. Existing coaching efforts can be adjusted to ensure that gathering insights is part of the plan, or the selection of coaches with specific skills around civility can be prioritized.

Individually focused training or empowerment programs can buffer against incivility by safeguarding employees’ personal resources (Porath et al., 2015). Training can help employees find work-life balance, including assistance with scheduling and making time for vacations. Training in mindfulness can also help. Those with greater levels of mindfulness tend to suffer less from incivility and are less likely to contribute to contagious or spiraling incivility. They may instead respond productively.

Emphasize and affirm political differences as a protected class of diversity

To maintain employees’ psychological safety and confidence that their employment does not depend on their political views, organizations should codify and enforce protections from harassment based on politics. This should also be confirmed by visible commitment to this policy—and enforcement when necessary (Baker, 2020). It is also helpful to ensure that specific events, namely elections, are addressed. If political discussion is to occur at work, create time and space for it or put forth an understanding that it is acceptable to use time and space for it. Training HR and leadership specifically to respond to election-related issues can help. This should include whether it is acceptable to ask for whom someone intends to vote and to make comments about anyone or any group that might vote in a certain way.

When employees feel out of place at work because of politics, this can lead to decreased job satisfaction and organizational commitment (He et al., 2019), discrimination (Thompson, 2021), and less identification with their profession (Zacher & Rudolph, 2023). Recruitment may also be affected; increasingly, employees make decisions on where to seek employment based on political fit (or the opposite) before applying (Roth et al., 2022). The employee screening process may lead to rejection of candidates for political reasons if the organization does not act to prevent it (Roth et al., 2020).

Moving to deemphasize groups and differences can also be helpful. Authoritarian leadership can draw stark divisions among employees (e.g., teams, roles, departments; Leiter, 2013). Counterintuitively, demographic lines among people may also be made more salient via poorly designed DEI interventions that encourage thinking in terms of ethnic, gender, and sexual orientation groupings. Leiter explained that “Clear differentiation among groups of employees increases the risk of incivility across boundaries. People apply different standards to their behavior towards out-group members than towards in-group members” (p. 33).

Corporate and employee activism

Among the most difficult challenges businesses face, regarding political polarization, is whether to participate in activism as an organization, typically referred to as “corporate activism.” The trend toward greater involvement of companies in politics brings risks of alienating some employees and/or customers. The organization may also find itself on the “wrong” side of an issue, whether from a mistake in judgment or a shift in political views. Backing specific politicians can go wrong when one takes an unpopular stance or becomes embroiled in scandal. Alternatives include supporting employees in pursuing activism of their choice or altogether avoiding issues of politics and activism.

A company must choose a path. Does it seek a rather apolitical orientation or an activist one? Both can be successful. Known for its strong environmental stance, outdoor clothing retailer Patagonia has navigated political polarization by adhering to its values and mission. The company encourages employees and customers to involve themselves in environmental causes, which can often be politically charged. However, in its first 40 years Patagonia focused on a shared love of nature rather than partisan politics (Chouinard & Stanley, 2012), which may explain how it avoided much controversy. Even after becoming quite political (e.g., suing the Trump administration, printing “vote the assholes out” on clothing tags), the company generally escaped threats of boycott (Chang, 2021; Seamon, 2018). A decades-long reputation for holding certain values may have sufficed to ensure that customers and employees knew and accepted its values. CEO Ryan Gellert has even admitted that Patagonia has become what he called a “mashup” of company and NGO.

The tech company Basecamp made headlines when it decided to ban political discussions at work (Newton, 2021). This policy can be seen as an attempt to mitigate the potential for conflict and distraction stemming from political polarization at work. However, the policy led to one-third of employees resigning. A controversial list of “Best Names Ever” (customer names that were deemed funny) had been collected by employees, but this was viewed as insensitive because the list of names included Asian and African names, while most of the staff was of European ancestry. Because Basecamp had an excellent reputation for diversity and inclusion, employees understandably felt it violated expectations for this list to have been tolerated by leadership for years. There came an end to the list and an apology for having allowed it, but a large rift remained between those who thought the list was the first step on a slippery slope toward hate and those who considered concerns about the list overblown.

Another tech company, Coinbase, made a similar decision to stop talking about politics. (Stratechery, 2022). Leaders of both Basecamp and Coinbase later said that they thought this was the best decision (Feldman, 2023). In 2022, Meta took a step in the same direction, asking employees to limit discussion of certain hot-button topics (Robison, 2022).