Women Can No Longer Pay for Household Help, and That’s a Problem

Janet Yellen, former Chair of the United States Federal Reserve, has been heralded for breaking gender barriers in the male-dominated field of economics. As one of the world’s top economists, currently appointed at the Brookings Institute, she is doubtless busy during the current economic crisis. Several weeks ago, though, the Washington Post reported that Yellen, 73, had been preparing plates of food for her adult son, who was quarantining in the basement of her home. Twitter was not impressed.

Her son had, in fact, gotten caught in a crowd at Dulles Airport passport control, and self-quarantine was a responsible decision on his part. But the event, and the response, highlight a widespread worry that with families trapped at home, the COVID-19 pandemic creates an unfair burden for women. Even as we talk about re-opening some parts of society, the lack of a plan for controlling the pandemic in the U.S. means that many families are expecting many more months basically at home.

Who cooks? Who cleans? Who cares for children? Who takes care of sick family members? Social norms have traditionally dictated that these arenas are women’s work. And expectations remain that women will be primarily responsible for taking care of the home. This is part of the reason that women in the U.S. do a disproportionate amount of housework and childcare, even when they are employed full-time.

Social distancing, and the threat of COVID-19, create a perfect storm for women heading households alone.

Of course, it is not feasible for fully employed women to also manage a household alone. As women have entered the U.S. labor market, other factors have shifted. Men in heterosexual relationships have taken on more household labor to make up the slack. But norms for the division of labor tend to stand in the way of full equality in the household.

To make up the gap, many women farm out household labor. Studies have found that the more money a woman makes in absolute terms, the less household labor she does. But, it does not seem to matter how much a woman makes relative to her husband. And how much her husband makes total does not matter either. This indicates that many women adhere to social norms and maintain responsibility for getting the “women’s work” done by buying themselves the needed time to work outside the home.

This might involve paying for childcare, hiring someone to clean the house, and buying take-out or going to restaurants instead of cooking. Women who cannot afford this sort of help take advantage of family to provide needed childcare. Government resources—free public schools, and subsidized early childcare—provide further help.

But the COVID-19 pandemic has stripped women of these resources. Across the nation, schools and daycares are closed. The swift spread of the virus means that even personalized childcare (for those who can afford it) may not be available. Restaurants are closed. Services like house cleaning are no longer safe for either providers or customers. And grandparents, who are typically part of the demographic most at risk for COVID-19 death, can no longer safely take the children.

Sherryse Corrow, a neuroscientist living in Minnesota, has a host of family members who are usually happy to watch her daughter when she and her husband need to get extra work done. But now these helpers are social distancing, school has gone remote, and their morning childcare provider has shut down. Despite having a good balance of housework under normal conditions, because Sherryse’s professor schedule is more flexible than her husband’s, she is now spearheading childcare and homeschooling, while also working full time. “I’m trying to work and parent and educate,” she laments, “and none of them are happening because you can’t do all those things at the same time and do them well.”

The situation is more dire still for single mothers, who account for about 80 percent of single parent households according to recent U.S. census data. This discrepancy is typical in many countries (in Britain that number is 90 percent), and follows, in part, from norms that identify mothers as both responsible for, and more qualified for, childcare. Social distancing, and the threat of COVID-19, create a perfect storm for women heading households alone. Single parents, perhaps more than any other demographic, depend on help from others—either paid or unpaid—to run their households and provide needed childcare.

“I feel like a lunatic, locked alone in a cage,” says Jackie Hendricks, single mother to a seven-month-old infant in Northern California. For a month now she has been alone in her home, providing full time care for her son. At the same time, Jackie is trying to work full time. From 7 P.M. until midnight, she works, but her son still wakes several times a night to nurse, and the lack of sleep is taking a toll.

Single mothers are also disproportionately likely to be poor. Women are paid less than men on average, and are more likely to hold part-time jobs. Again, this discrepancy arises at least in part from norms that label men as primary breadwinners. Poverty presents challenges under the best scenarios, but the economic downturn resulting from COVID-19 is creating new stresses, especially with public-school services no longer available.

Carmen Crafts, a single mother living in upstate New York, recently lost her position as a substitute teacher when schools closed. While she receives child support, her child’s father has now lost his job in the food service industry too. In a struggling economy, she worries she won’t be able to find a job after graduating from her Master’s program in social work this spring.

All these factors are exacerbated by issues related to race and racism. Black women are more likely than other demographics to be single parents, are paid less than white women, and are more likely to be poor. Structural factors mean that Black women may be more likely to get sick with COVID-19. And racism in the medical field makes them less likely to receive proper medical care when they do.

What can we do in the light of the gender norms, racial biases, and structural issues, that are hurting women during this pandemic? As we move to the next stages of the pandemic, we need solutions to provide working parents, and especially single parents, with childcare. While larger childcare centers that bring many adults into contact may be dangerous, in-home babysitters and nannies only slightly increase risks of spreading COVID-19. A small trade-off in risk can yield enormous economic benefits. The government should be providing subsidies for this sort of in-home childcare. This has the double benefit of creating employment opportunities for those who suddenly find themselves out of work as COVID-19 cripples the U.S. economy.

Cailin O’Connor is an Associate Professor in the Department of Logic and Philosophy of Science at UC Irvine, where she is a member of the Institute for Mathematical Behavioral Science. Her research focuses on the philosophy of biology and behavioral sciences as well as evolutionary game theory. Follow her on Twitter @cailinmeister.

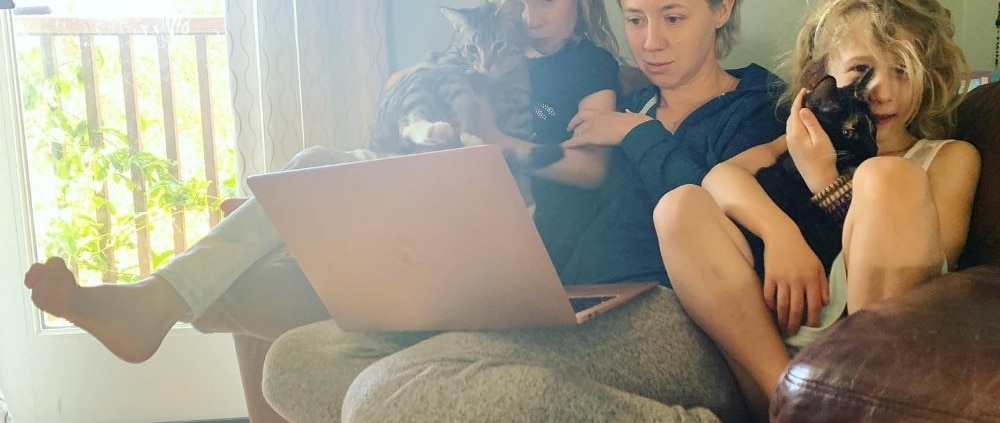

Image: The author attempting to submit grades.

This post was originally published on Medium, and is reprinted with permission.