Why Modern Meritocracy Is Broken

If the 2016 election felt like a polarizing set of choices for American voters, the upcoming election makes that one look almost benign. Never has America been more divided as we struggle through a pandemic, trying to put people back to work whose jobs were impacted by it and to maintain civil peace as people express outrage over our nation’s long history of unaddressed racial injustice. And now, oh yes, the appointment of a new supreme court justice to fill the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg’s seat. On top of all that, we have the usual persistent battles—access to quality healthcare, economic inequality, national security and immigration, and cyber security over our electoral process and our personal information.

As politicians hammer on these issues in the coming weeks, scrambling to sway the electorate, they may be missing the one thing that could actually persuade a vast majority of Americans who are arguably feeling most angry and left behind.

Telling those who feel they are falling further behind to simply try harder only fuels their outrage and humiliation.

I spoke with Harvard philosopher Michael Sandel about his new book, The Tyranny of Merit: What’s Become of the Common Good. In a close study of the populist backlash leading up to the last election’s results, Sandel argues with compelling insight that for many Americans, the fundamental discontent is not just the lack of economic opportunity for so many whom globalization left behind, it’s the dignity of work, and particularly the work they do. Sandel told me, “Both mainstream parties have missed their responsibility in fostering policies and attitudes that have demeaned working class people. They are missing the tendency of meritocratic elites to look down on those who haven’t flourished in the new economy.”

Meritocracy, the noble ideal that one has agency over their own success by the merits of their talents and hard work, has failed in practice for many. Two-thirds of Americans don’t have college degrees, nor do they have access to pursuing one. So, the rhetoric of the politicians over the last 20 years of “rising” in social status has long lost its charm and credibility. Both parties have recited some version of “You have the right to rise up as far as your God-given talents and hard work can take you” to the point of incantation. But for many Americans, that’s just not been true.

The meritocratic elites who have flourished in a globalized economy look down in hubris on those that haven’t done well. Sandel told me, “Over the past four decades, the divide between winners and losers has deepened. What’s made it all the more galling for those who haven’t flourished in the new economy is the sense among the winners that their success is their due—they’ve made it on their own and therefore deserve their winnings. By implication, the attitude among the successful is that those left behind must deserve their fate as well, that they have no one to blame but themselves.”

The hubris of the “winners” has led to their loss of humility. Some of their success is due to luck, and the result of help from others. Their arrogance limits their ability to see themselves in other’s shoes. And telling those who feel they are falling further behind to simply try harder only fuels their outrage and humiliation. In a stinging indictment of American governance, Sandel writes how leaders have failed.

“Over the past four decades, meritocratic elites have not governed very well. The elites who governed the United States from 1940 to 1980 were far more successful. They won World War II, helped rebuild Europe and Japan, strengthened the welfare state, dismantled segregation, and presided over four decades of economic growth that flowed to rich and poor alike. By contrast, the elites who have governed since have brought us four decades of stagnant wages for most workers, inequalities of income and wealth not seen since the 1920s, the Iraq War, a nineteen-year, inconclusive war in Afghanistan, financial deregulation, the financial crisis of 2008, a decaying infrastructure, the highest incarceration rate in the world, and a system of campaign finance and gerrymandered congressional districts that makes a mockery of democracy.”

Subscribe to the Ethical Systems newsletter

Sandel suggests at the heart of meritocratic failure is “credentialism,” what he calls “our last acceptable prejudice.” Those without society’s most esteemed credentials, notably college degrees, are sent the inferred message of inadequacy, that their contributions aren’t as valuable to society as those prized by a higher education. More than just the economic opportunities to thrive, what working-class people have lost is their sense of pride, their confidence in fitting into the broader fabric of society and making as meaningful a contribution as anyone else. And meaningful not defined by the financial rewards, but by the esteem of peers and those they serve.

Ironically, the pandemic has suddenly designated many such professionals as “essential” and has poured out heaps of well-deserved appreciation on them. Healthcare workers, grocery store clerks, truck drivers, trades people, teachers, and the like have been thrust into the spotlight of gratitude for their sacrificial efforts to serve. But their dedication isn’t new. It took a pandemic to recognize it for the dignified contribution it is. When the pandemic eventually recedes, will we continue to esteem their work, or re-relegate them to “lesser than” status?

In his Atlantic article, Sandel writes, “Globalization brought rich rewards to the well credentialed—the winners of the meritocratic race. It did nothing for most workers. Productivity increased, but working people reaped a smaller and smaller share of what they produced. Although per capita income in the U.S. has increased 85 percent since 1979, white men without a four-year college degree make less now, in real terms, than they did then.”

America has, as a result, sent a loud and clear disparaging message to the working class: What you do is a lesser contribution to the common good. And for good reason, they are fed up with hearing it, tired of the sense of self-contempt such judgements have led them to feel.

Leaders in public service and within our workplaces would do well to restore the dignity of work in the policies they create, in the job solutions they offer, and in the way they lead their organizations.

Sandel said, “We need to face the inequality brought about by globalization and not assume that the best and only solution is individual upward mobility with a college degree. That was the promise both parties offered for decades. Put the dignity of work at the center of politics and public discourse. People may disagree about what it means, but that should be the debate. The rhetoric of rising doesn’t fit the facts on the ground. It’s an inadequate response.”

Employers like Google, IBM, and Microsoft have stopped requiring four-year degrees as a condition of employment. This is certainly a positive start to leveling the playing field. But accountability systems even within large corporations have strayed from their ideal of meritocracy, even where many have such credentials. The systems are also failing to provide a sense of dignity to those being homogenized by force rankings, biased ratings, poor feedback, and utilitarian leadership that doesn’t recognize employee’s personal connections to their contributions.

Workplaces have confused “sameness” with “fairness,” which is exactly what makes them undignifying. In my research for my forthcoming book, To Be Honest: Lead with the Power of Truth, Justice, and Purpose, I learned that when people deem their accountability systems as unfair, the organization is four times more likely to have people lie, behave unjustly toward others, and put their own interests first.

In society at large, and within our workplaces, we need to make one another’s dignity central to our conversations and debates. Rather than perpetuating rancor, let’s own up to the fact that there are many around us whose sense of social esteem and contribution has been reduced.

As you cast your votes at the federal, state and local level, listen closely for messages and solutions that put the dignity of all workers at the center of policy solutions. Reject the rhetoric of rising messages that have rung hollow. Within your organizations, take stock of those you lead and work with. Are there some jobs or tasks your organization prizes too little? Are there people who feel overlooked, or whose sense of dignity you’ve neglected?

Our ideological ghettos have ripped us apart, and we have vilified those different than us—politically, racially, religiously, and professionally, we have created our collection of “theys.” Do an honest soul-searching of your own credentialism and see whose work you have treated as “lesser than.” Whose misfortune have you reflexively relegated to their own doing? Where have you withheld compassion from those who would welcome the chance to make a meaningful contribution to the common good, even if different than the one you make? Where has your own hubris blinded you to humility, to acknowledge that your success wasn’t entirely your own doing?

Sandel writes, “…we are most fully human when we contribute to the common good and earn the esteem of our fellow citizens for the contributions we make. According to this tradition, the fundamental human need is to be needed by those with whom we share a common life. The dignity of work consists in exercising our abilities to answer such needs.”

What would happen within our communities, organizations, and across our nation, if we actually treated one another as if this were true?

Ron Carucci is an Advisory Board member of Ethical Systems as well as cofounder and managing partner at Navalent, working with CEOs and executives pursuing transformational change for their organizations, leaders, and industries. He is the bestselling author of eight books, and his work has been featured in Fortune, CEO Magazine, Harvard Business Review, BusinessInsider, MSNBC, BusinessWeek, and Smart Business.

Reprinted with permission from Forbes.

Lead image: Jonathan Khoo / Flickr

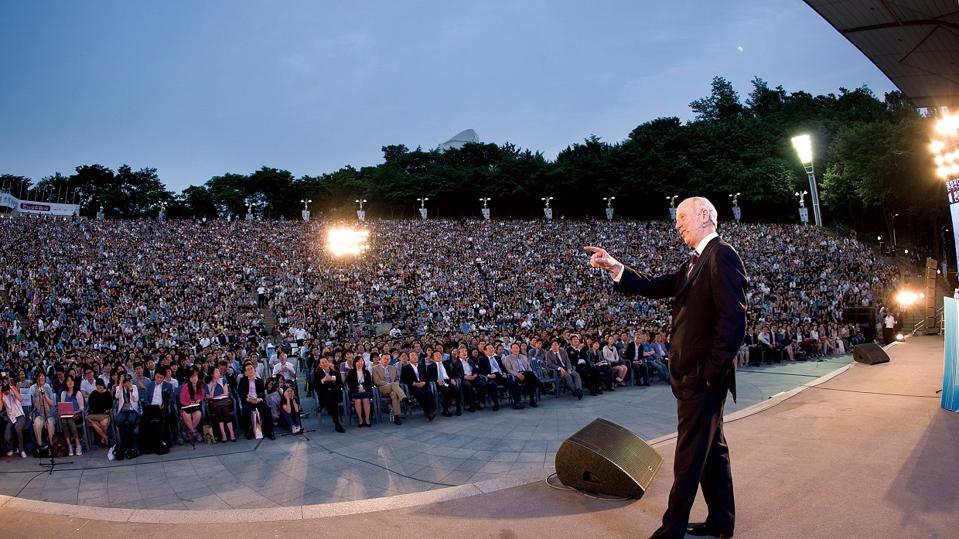

Breaker image is courtesy of the Asian Institute for Policy Studies, Seoul, S. Korea.