What the Right Gets Wrong About Adam Smith

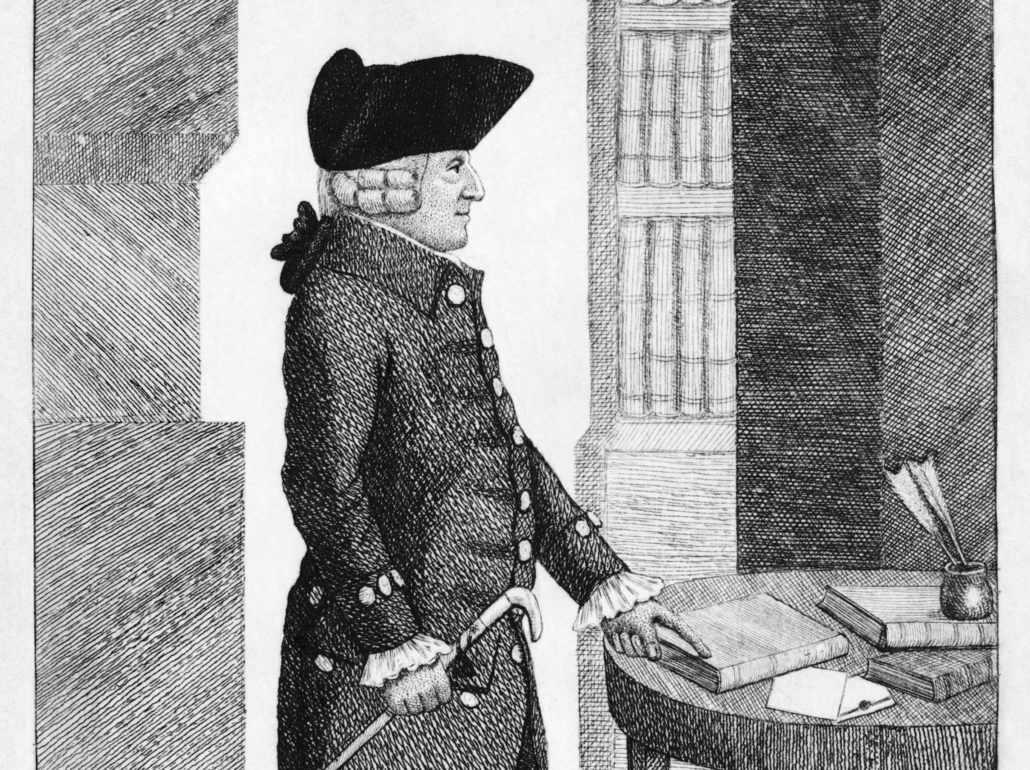

What to make of Adam Smith? You might have thought we would have straightened this out, given that he only ever wrote two books and it’s been 300 years since he was born. But no. Everyone wants to claim the Scottish philosopher and economist as one of their own. With the exception of Jesus, it’s hard to think of anyone who attracts such radically different interpretations.

Part of the problem is that we actually know very little about the man. Smith oversaw the burning of all his unpublished writings as he lay on his death bed—a common practice at the time, but not much help in settling endless arguments.

What we know is that he was born in the town of Kirkcaldy on the east coast of Scotland. His father was a judge who died just before he was born. Smith seems to have been a very scholarly child, rarely seen without a book about his person.

One early experience that seems to have affected him concerned the town market. Certain landowners were exempt from Kirkcaldy’s bridge tolls and market stall charges due to the town’s status as a royal burgh. This gave them a competitive advantage over their competitors, which did not sit well with the young Smith.

He left his mother at the age of 14 to study moral philosophy at the University of Glasgow, before completing his postgraduate studies in metaphysics at Balliol College Oxford. Thereafter he went on to spend his life studying, teaching, and writing in the fields of philosophy, theology, astronomy, ethics, jurisprudence, and political economy. Most of his career was spent as an academic in Edinburgh and Glasgow, though there were also stints as a private tutor in France and London.

The Wealth of Nations

The two books that Smith published in his lifetime are The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) and his more widely known, An Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776). The latter, a rambling 700-page text published over two volumes, was 17 years in the making.

The dominant economic ideology of the time was known as mercantilism. It viewed economic value simply in terms of the amount of gold that a country had to buy the goods it needs. It gave little consideration to how goods were produced—either the physical inputs or the human motivation.

But for Smith, motivation was at the heart of economic behavior. He saw it as an all-purpose lubricant that delivers mutual benefit for all:

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.

Smith’s observations about how the division of labour can be organised to increase productivity remains one of his most enduring contributions to economics. Improving productivity is still seen as the holy grail for countries getting richer. Larry Fink, head of investment giant BlackRock, has only just been arguing that artificial intelligence could improve productivity, for instance.

The Battleground

The Wealth of Nations is an eclectic text—even an “impenetrable” one, according to the director of the Adam Smith Institute. Smith argues that slavery and feudalism are bad and that economic growth and getting people out of poverty are good.

He thinks high wages and low profits are good. He also warns against things like cronyism, corporate corruption of politics, imperialism, inequality and the exploitation of workers. In observations about the British East India Company, which was the Amazon of its day and then some, Smith even warned about companies becoming too big to fail.

Those on the right of the debate often cite Smith’s “invisible hand” phrase from the Wealth of Nations in support of their worldview. Borrowed from Shakespeare’s Macbeth, the phrase actually appears only once in the whole text. It is a metaphor for how a “free” market magically brings buyers and sellers together without any need for government involvement.

In more recent times, “invisible hand” has come to mean something slightly different. Chicago School free market advocates like Milton Friedman and George Stigler viewed it as a metaphor for prices, which they saw as signalling what producers wanted to produce and buyers wanted to buy. Any interference from government in terms of price controls or regulations would distort this mechanism and should therefore be avoided.

Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher were disciples of this way of thinking. In a 1988 speech encouraging his people to be thankful for the prosperity that comes from free trade, President Reagan argued that the Wealth of Nations “exposed for all time the folly of protectionism.”

Yet those on the left also find plenty in Smith that resonates with them. They often cite his concern for the poor in the Theory of Moral Sentiments:

This disposition to admire, and almost to worship, the rich and the powerful, and to despise, or, at least, to neglect persons of poor and mean condition, though necessary both to establish and to maintain the distinction of ranks and the order of society, is, at the same time, the great and most universal cause of the corruption of our moral sentiments.

In 2013, President Barack Obama cited Smith in a speech to support raising the US minimum wage:

They who feed, clothe and lodge the whole body of the people should have such a share of the produce of their own labor as to be themselves tolerably well fed, clothed and lodged.

States and Abuses

So how to square this circle? The truth is that Smith’s writing has enough ideas and inconsistencies to allow for all sides to cherry pick references as required. But one argument I find compelling, which has been put forward by the economist Mariana Mazzucato, is that many of those who champion laissez-faire policies misinterpret Smith’s notion of a free market.

This is linked to the fact that Smith was writing at a time when the British East India Company was responsible for a staggering 50 percent of world trade. It operated under a royal charter conferring a monopoly of English trade in the whole of Asia and the Pacific. It even had its own private army.

Subscribe to the Ethical Systems newsletter

Smith was presenting an alternative vision for the UK economy in which such state-licensed monopolies were replaced by firms competing against one another in a “free” market. Innovation and competition would provide employment, keep prices down and help reduce the appalling levels of urban poverty of the time. This was capitalism. And ultimately Smith was proved correct.

But Mazzucato argues that when Smith talked about the free market, he didn’t mean free from the state, so much as free from rent and free from extraction of value from the system. In today’s world, the equivalent example of such feudal extraction is arguably global tech firms like Amazon, Apple and Meta playing nations off against one another to minimise their regulations and tax liabilities.

This doesn’t sound like the sort of “free” market that Smith envisaged. He would probably be cheering on the EU’s anti-trust case against Google, for instance. Those who believe that Smith saw no role for the state in managing the economy ought to reflect on how spent his final years—working as a tax collector.

Reprinted with permission from The Conversation.