The Value of Psychological Flexibility During a Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic, and our response to it, has foisted considerable uncertainty into the personal and professional lives of humans across the planet. Lockdowns, travel restrictions, physical distancing, and the shift to remote work has the potential to seriously stress and compromise how well both individuals and organizations function. Left unchecked, the economic and personal costs may be devastating. This raises the question: “What might we be doing now to promote individual and organizational resilience and well-being?” Fortunately, a construct from the behavioral-change sciences with documented links to human health and well-being may prove useful in navigating the COVID-19 storm: psychological flexibility.

Psychological flexibility is the ability to maintain contact with the present moment and act in accordance with one’s values, even in the presence of distressing or unwanted inner experiences (like thoughts, emotions, sensations). People low on psychological flexibility are more readily “hooked” by inner experiences, drawn away from the present moment, and run the real possibility of becoming stuck in unworkable behavioral patterns motivated more by a desire to “escape” or “control” those inner experiences (rather than acting in a manner that moves them towards what is important to them).

There is a rich empirical literature outlining the association between psychological flexibility and human health and well-being. In clinical settings, interventions targeting psychological flexibility have proven effective in treating anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and substance abuse; and these programs can be delivered in person, online, via apps, or books alone.1 Studies in the workplace show that the psychological flexibility of employees is associated with, and predictive of, multiple work-related outcomes, including better job performance, improved learning on the job, innovation, and overall mental health, as well as lower levels of stress and emotional exhaustion.2

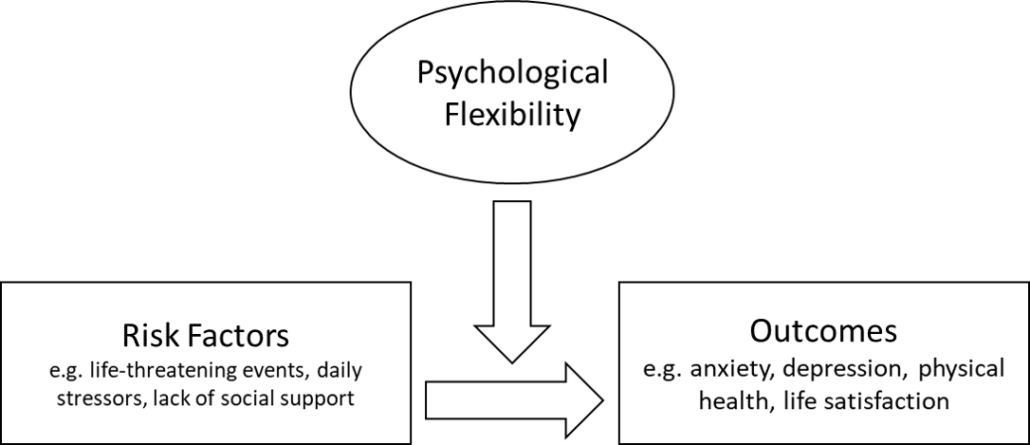

The strong association with human health across a range of contexts has led some to propose psychological flexibility should be an important and “malleable” resilience target for public health interventions.3 Research using a representative sample of the Swiss population suggests higher levels of psychological flexibility acts as a protective buffer, moderating the connection between common risk factors—like lack of social support, threatening life experiences, and daily stressors—and a range of outcomes, like anxiety, depression, and overall physical health.

Adapted from Gloster, Meyer and Kieb (2017).

Notice how our current, pandemic-imposed reality is characterized by all three of these major risk factors: a life-threatening situation (virus), elevated daily stressors (upheaval of personal and professional routines) and increased social isolation (through physical distancing). So, how might we step back from our immediate, and very human, reflexive reactions to the pandemic, and allow space for more intentional, value-guided responses to emerge, both individually and collectively?

The good news is that psychological flexibility is a skill, and, like any skill, it can be improved with practice over time. Below we present a short video to introduce one tool, the personal matrix, that you can use to help you and others to develop psychological flexibility. If you want to learn more about different approaches to psychological flexibility, we highly recommend you take a look at Steven Hayes’s latest book, A Liberated Mind: How to Pivot Toward What Matters. And you can learn about how to use the personal matrix in responding to COVID-19 as a family here.

Ian F. MacDonald is a researcher with a background that straddles human behavioural ecology and cultural evolutionary science. He received his PhD in Ecology, Evolution & Behavior from Binghamton University in 2018. He currently oversees Prosocial.World data collection efforts and is developing his practice as a cultural design consultant.

Paul Atkins is a visiting Associate Professor at the Crawford School of Public Policy, where he has taught leadership for many years. He co-developed the Prosocial process, which draws on the psychology of behavior change as well as political, economic, and evolutionary science to improve cooperation within and between groups.

References

1. Atkins, P. W., Ciarrochi, J., Gaudiano, B. A., Bricker, J. B., Donald, J., Rovner, G., … & Hayes, S. C. (2017). Departing from the essential features of a high quality systematic review of psychotherapy: A response to Öst (2014) and recommendations for improvement. Behaviour research and therapy, 97, 259-272.

2. Bond, F. W., Lloyd, J., & Guenole, N. (2013). The work‐related acceptance and action questionnaire: Initial psychometric findings and their implications for measuring psychological flexibility in specific contexts. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 86(3), 331-347.

Bond, F. W., Lloyd, J., Flaxman, P. E., & Archer, R. (2016). Psychological flexibility and ACT at work. In R. D. Zettle, S. C. Hayes, D. Barnes-Holmes, & A. Biglan (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of contextual behavioral science (p. 459–482). Wiley-Blackwell.

3. Gloster, A.T., Meyer, A.H. and Lieb, R. (2017). Psychological flexibility as a malleable public health target: Evidence from a representative sample. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 6(2), 166-171.