The Secrets of Cooperation

People stop their cars simply because a little light turns from green to red. They crowd onto buses, trains and planes with complete strangers, yet fights seldom break out. Large, strong men routinely walk right past smaller, weaker ones without demanding their valuables. People pay their taxes and donate to food banks and other charities.

Most of us give little thought to these everyday examples of cooperation. But to biologists, they’re remarkable—most animals don’t behave that way.

“Even the least cooperative human groups are more cooperative than our closest cousins, chimpanzees and bonobos,” says Michael Muthukrishna, a behavioral scientist at the London School of Economics. Chimps don’t tolerate strangers, Muthukrishna says, and even young children are a lot more generous than a chimp.

Human cooperation takes some explaining—after all, people who act cooperatively should be vulnerable to exploitation by others. Yet in societies around the world, people cooperate to their mutual benefit. Scientists are making headway in understanding the conditions that foster cooperation, research that seems essential as an interconnected world grapples with climate change, partisan politics and more—problems that can be addressed only through large-scale cooperation.

Compared with other animals, humans are unusually good at cooperating.

Behavioral scientists’ formal definition of cooperation involves paying a personal cost (for example, contributing to charity) to gain a collective benefit (a social safety net). But freeloaders enjoy the same benefit without paying the cost, so all else being equal, freeloading should be an individual’s best choice—and, therefore, we should all be freeloaders eventually.

Many millennia of evolution acting on both our genes and our cultural practices have equipped people with ways of getting past that obstacle, says Muthukrishna, who coauthored a look at the evolution of cooperation in the 2021 Annual Review of Psychology. This cultural-genetic coevolution stacked the deck in human society so that cooperation became the smart move rather than a sucker’s choice. Over thousands of years, that has allowed us to live in villages, towns and cities; work together to build farms, railroads and other communal projects; and develop educational systems and governments.

Evolution has enabled all this by shaping us to value the unwritten rules of society, to feel outrage when someone else breaks those rules and, crucially, to care what others think about us.

“Over the long haul, human psychology has been modified so that we’re able to feel emotions that make us identify with the goals of social groups,” says Rob Boyd, an evolutionary anthropologist at the Institute for Human Origins at Arizona State University.

For a demonstration of this, one need look no further than a simple lab experiment that psychologists call the dictator game. In this game, researchers give a sum of money to one person (the dictator) and tell them they can split the money however they’d like with an unknown other person whom they will never meet. Even though no overt rule prohibits them from keeping all the money themselves, many people’s innate sense of fairness leads them to split the money 50-50. Cultures differ in how often this happens, but even societies where the sense of fairness is weakest still choose a fair split fairly often.

Lab experiments such as this, together with field studies, are giving psychologists a better understanding of the psychological factors that underpin when, and why, people cooperate. Here are some of the essential takeaways:

We cooperate for different reasons at different social scales

For very small groups, family bonds and direct reciprocity—I’ll help you today, on the expectation that you will help me tomorrow—may provide enough impetus for cooperation. But that works only if everyone knows one another and interacts frequently, says Muthukrishna. When a group gets big enough that people often interact with someone they’ve never dealt with before, reputation can substitute for direct experience. In these conditions, individuals are more likely to risk cooperating with others who have a reputation for doing their share.

Once a group gets so large that people can no longer count on knowing someone’s reputation, though, cooperation depends on a less personal force: the informal rules of behavior known as norms. Norms represent a culture’s expectations about how one should behave, how one should and shouldn’t act. Breaking a norm—whether by littering, jumping a subway turnstile or expressing overt racism—exposes violators to social disapproval that may range from a gentle “tut-tut” to social ostracism. People also tend to internalize their culture’s norms and generally adhere to them even when there is no prospect of punishment—as seen, for example, in the dictator game.

But there may be a limit to the power of norms, says Erez Yoeli, a behavioral scientist at the MIT Sloan School of Management. The enforcement of norms depends on social disapproval of violators, so they work only within social groups. Since nations are the largest groups that most people identify strongly with, that may make norms relatively toothless in developing international cooperation for issues such as climate change.

“The problem isn’t owned by a single group, so it’s kind of a race to the bottom,” says Yoeli. Social skills that go beyond cooperation, and psychological tools other than norms, may be more important in working through global problems, he speculates. “These are the ones we struggle a bit to solve.”

Reputation is more powerful than financial incentives in encouraging cooperation

Almost a decade ago, Yoeli and his colleagues trawled through the published literature to see what worked and what didn’t at encouraging prosocial behavior. Financial incentives such as contribution-matching or cash, or rewards for participating, such as offering T-shirts for blood donors, sometimes worked and sometimes didn’t, they found. In contrast, reputational rewards—making individuals’ cooperative behavior public—consistently boosted participation. The result has held up in the years since. “If anything, the results are stronger,” says Yoeli.

Financial rewards will work if you pay people enough, Yoeli notes — but the cost of such incentives could be prohibitive. One study of 782 German residents, for example, surveyed whether paying people to receive a Covid vaccine would increase vaccine uptake. It did, but researchers found that boosting vaccination rates significantly would have required a payment of at least 3,250 euros—a dauntingly steep price.

And payoffs can actually diminish the reputational rewards people could otherwise gain for cooperative behavior, because others may be unsure whether the person was acting out of altruism or just doing it for the money. “Financial rewards kind of muddy the water about people’s motivations,” says Yoeli. “That undermines any reputational benefit from doing the deed.”

Gossip plays a lead role in enforcing norms

When people see someone breaking a norm—for example, by freeloading when cooperation was expected—they have three ways to punish the violation, says Catherine Molho, a psychologist at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam: They can confront the offender directly about their transgression; they can shun that person in the future; or they can tell others about the offender’s bad behavior. The latter response—gossip, or the sharing of information about a third party when they are not present—may have unique strengths, says Molho.

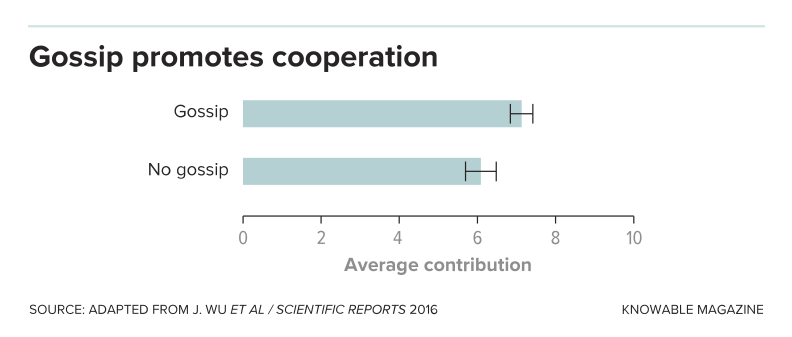

The clearest example of this comes from an online experiment led by Molho’s colleague Paul Van Lange, a behavioral scientist also at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. The study used a standard lab procedure called a public goods game, in which each participant receives a sum of money and can choose to contribute none, some or all of it to a shared pool. The experimenters then double the money in the shared pool and divide it equally among all participants, whether they contributed or not. The group as a whole maximizes their earnings if everyone puts all their money in the pool—but a freeloader could do even better, by keeping their own cash and reaping a share of what others put in the pool.

Crucially, people played the game not just once but four times, with different partners each time. Between rounds, some participants had an opportunity to punish freeloaders from their most recent group by paying some of their own money to the experimenters, who would fine the freeloader three times the amount of that payment. Others were given the chance to gossip—that is, to tell members of the freeloaders’ new group that they had failed to cooperate. Sure enough, the gossip led to higher levels of cooperation—but, surprisingly, direct punishment did not, the researchers found.

People use the power of gossip in the real world, too. In one recent study, Molho and her colleagues texted 309 volunteers at four random times each day for 10 days to ask if they had shared information with others in their social network, or received information from them, about someone else. If so, a follow-up questionnaire gathered more information.

The 309 participants reported more than 5,000 total instances of gossip over that time, and about 15 percent were about norm violations such as tossing trash in the street or making racist or sexist comments. People tended to gossip more with closer friends, and about more distant acquaintances. Gossip recipients reported that this negative information made them less likely to help the untrustworthy and more likely to avoid them.

“One reason gossip is such a powerful tool is you can accomplish many social functions,” says Molho. “You feel closer to the person who shared information with you. But we also find it provides useful information for social interaction—I learn who to cooperate with and who to avoid.”

And gossip serves another function, too, says Van Lange: Gossipers can sort through their feelings about whether a norm violation is important, whether there were mitigating circumstances and what response is appropriate. This helps reinforce the social norms and can help people coordinate their response to offenders, he says.

We like being on trend—and on the cutting edge

Some well-meaning ways of encouraging cooperation don’t work—and may even backfire. In particular, telling people what others actually do (“Most people are trying to reduce how often they fly”) is more effective than telling them what they should do (“You should fly less—it’s bad for the climate”). In fact, the “should” message sometimes backfires. “People may read something behind the message,” says Cristina Bicchieri, a behavioral scientist at the University of Pennsylvania: Telling someone they should do something may signal that people don’t, in fact, do it.

Bicchieri and her colleague Erte Xiao tested this in a dictator game where some participants were told that other people shared equally, while others were told that people thought everyone should share equally. Only the first message increased the likelihood of an equal share, they found.

That result makes sense, says Yoeli. “It sends a very clear message about social expectations: If everybody else is doing this, it sends a very credible signal about what they expect me to do.”

This poses a problem, of course, if most people don’t actually choose a socially desirable behavior, such as installing solar panels. “If you just say that 15 percent do that, you normalize the fact that 85 percent don’t,” says Bicchieri. But there’s a work-around: It turns out that even a minority can nudge people toward a desired behavior if the number is increasing, thus providing a trendy bandwagon to hop on. In one experiment, for example, researchers measured the amount of water volunteers used while brushing their teeth. People who had been told that a small but increasing proportion of people were conserving water used less water than those who heard only that a small proportion conserved.

Much remains unknown

Behavioral scientists are just beginning to crack the problem of cooperation, and many questions remain. In particular, very little is known yet about why cultures hold the norms that they do, or how norms change over time. “There’s a lot of ideas about the within-group processes that cause norms to be replaced, but there’s not much consensus,” says Boyd, who is working on the problem now.

Everyone does agree that, eventually, natural selection will determine the outcome, as cultures whose norms do not enhance survival die out and are replaced by those with norms that do. But that’s not a test most of us would be willing to take.

Bob Holmes is a science writer based in Edmonton, Canada.

Lead image: Maria Hergueta

Reprinted with permission from Knowable Magazine.