The Entrepreneur Who Wants Us to Rethink What’s Worth Wanting

A powerful idea, that of mimetic desire, seems to be getting out there, spreading like a compelling meme. Chloe Valdary, for example—the Black entrepreneur who was profiled this year in The Atlantic concerning her heterodox antiracism programs—said yesterday, on Twitter, that she recently learned about mimesis theory, and found it fascinating. “When liminality”—meaning a period of radical transition, or a dissolution of order culturally or politically—“exists on a societal scale, the likelihood of mimetic rivalry and scapegoating increases exponentially,” she wrote. “I see mimetic rivalry all over Twitter. Once you see it, it’s hard to unsee it.”

Valdary’s next tweet was perfect, for me. She shared a link to a “relevant book” by Luke Burgis, Wanting: The Power of Mimetic Desire in Everyday Life. This allows an easy transition to my conversation with the author, once a serial entrepreneur who is now on the other side of a crisis of meaning and disillusionment, thanks to the ideas of Rene Girard.

“Mimetic theory,” Burgis writes in Wanting, “would help me recognize patterns in the behavior of people and in current events. That was the easy part. Later, after seeing mimetic desire everywhere except in my own life, I saw it in myself—my Holy shit moment.” Girard’s ideas helped him make sense of, and declutter, his own tangled web of desires. He came to a better understanding of why he wanted what he wanted, stepping away from entrepreneurship for a few years before immersing himself in it again. He thinks not only individuals but companies and countries can benefit from exposing how mimetic desire can drive us toward undesirable places.

Business, at the end of the day, is, to me, about loving and serving people.

Burgis, who has studied philosophy and theology in Rome, sees business as an almost spiritual calling. That came through in our conversation as he discussed, among other things, the importance of truth, and how the speed of its travel, through an organization, can reveal the values or health of its culture. And, of course, Burgis didn’t leave without sharing his thoughts on how mimetic desire can inform the design of more ethical workplaces.

You hint, early in the book, at how deep or profound “mimetic desire” is by noting how it connects “the collapse of ancient civilizations with workplace dysfunction.” Could you give us a sense of what mimetic desire is by explaining that strange link—how our job issues are tied to bygone eras?

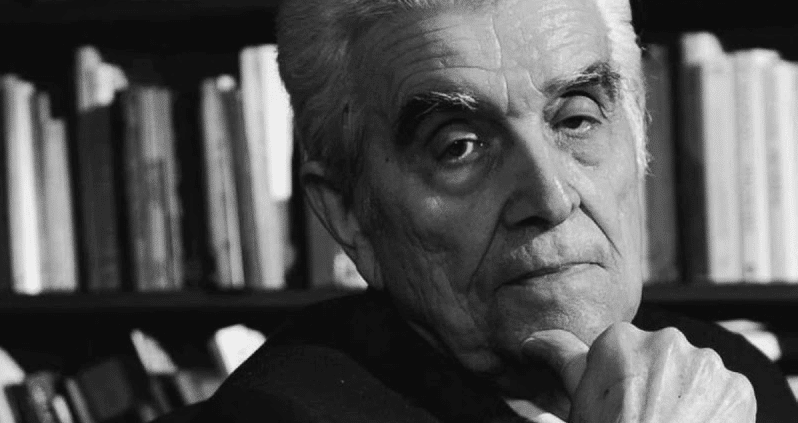

I drew the connection between the collapse of ancient civilizations and workplace dysfunction because the cycles of mimetic desire that plagued our ancestors play out in organizations today. Mimetic desire is the hard-wired, human inclination to want what other people want. The French thinker René Girard (1923-2015), who taught at Stanford for many years, was the first to notice the dangerous implications of this phenomenon. Because human desire is by nature mimetic, or imitative, it tends to result in rivalry. Few people realize that they’re caught up in the kind of mimetic crisis that Girard described while they are actually in it. But our workplace dysfunctions are not new. We have the same human nature as the people living in ancient civilizations that Girard studied. If we don’t learn how these mimetic cycles of conflict take shape and lead to dysfunction and scapegoats, we’re doomed to repeat the same mistakes.

How do mimetic cycles of conflict take shape?

In any society, when people want what other people want, it leads them to view others—their models of desire (in Girardian terms)—as obstacles or scandals to their own pursuit of fulfillment. Once enough people engage in this kind of rivalrous conflict, it spreads quickly through a culture, or a company. Girard, a historian by training, saw that societies went through cycles of conflict caused by out-of-control mimetic desire that spread through groups, and which led to a war of all-against-all. This could be in the form of deeply destabilizing class conflict, interpersonal tensions, political polarization, accusations, or confusion about who is a model of desire and who is not. Societies that didn’t find a way to defuse or de-escalate these mimetic crises eventually collapsed from the inside (that, or the internal crisis weakened or distracted them from outside threats, which made them easier to conquer).

At one point in your entrepreneurial career, you write, you became “infected with the Zappos culture mania.” What do you mean by that? And what sort of emphasis or focus do you think is appropriate for companies to give to their “culture”? Do companies that put a lot of stock in their culture, however defined, risk developing an unhelpful fixation on it?

I imitated the culture of Zappos like a Cargo Cult. It was as if I believed that by imitating all of the superficial aspects of the company culture (the way people decorated their desks, the frequency of social events, the style of meetings), I would magically increase my company’s valuation.

It’s a tempting way to think—that we can simply snap on another company’s culture to our own.

They need to develop organically, and there is no formula. There are, however, some key things that make the likelihood of success much higher, just like there are in a family. There are foundational ethical principles. In a family: be faithful to your spouse; develop trust; encourage open and honest communication. Companies also have ethical principles that allow a healthy culture to grow. But just as every family develops its own culture organically, so do companies.

Should company leaders be cautious, then, when looking to deliberately change work culture?

One danger I see: companies attempting to socially engineer culture from the top-down, in which CEO’s or leaders try to force their beliefs about everything from politics to social justice on everyone else. The increasing homogeneity and loss of ideological diversity at many companies today signals something troubling. I think it’s due to an excessive focus on the wrong cultural dimensions: on appearances, or what the Italians call the bella figura. This would be like a basketball coach who was more concerned with the style of his team’s uniforms than the culture in the locker room. The legendary UCLA basketball coach John Wooden started, in building his team’s culture, by focusing on one very important and concrete thing: making sure his players demonstrated that they knew how to tie their shoes correctly to avoid problems with injuries on the court. First principles matter. You want a company culture where people know how to tie their shoes.

Subscribe to the Ethical Systems newsletter

If someone looking to design an ethical workplace culture came to you curious about how mimetic desire might be useful, what would you say?

I’d say there are a few key things to start with. I learned through many years of trial and error because they’re so easy to overlook. First, be extremely intentional about defusing unhealthy forms of rivalry. Put leaders in place who aren’t rivalrous—the kind who see themselves as mentors and midwives to the careers of the people around them rather than seeing them as threats.

Second, root out any and all forms of scapegoating from your company culture. That includes not letting contagious accusations and crowds wield power by singling out individuals who bear the consequences of everyone’s collective workplace or ethical “sins.” Yet this happens all the time. It’s unethical behavior in the name of ethics. There needs to be due process.

Third, understand mimetic desire so you can harness it as a force for good. There are ways to create positive cycles of desire, or positive flywheels of desire, within the company. A fundamental ethical perspective for any leader to embrace is this: think not just about what effect management decisions and policies have on behaviors, but fundamentally on desires—on what people want. Imagine if we rewarded the development of key moral virtues (honesty, courage, prudence) one-tenth as much as we rewarded those who meet sales targets.

I really appreciated your discussion about the power of sharing “stories of deeply fulfilling action.” It got me to happily think of my own. I think you’re right that sharing these could help coworkers connect. What would you think if a company had its employees take time to share these stories with one another? Should leaders facilitate those conversations or let them happen organically?

I’ve been doing it for 10 years, and it’s transformative. It builds a culture where people know one another at an essential level: their stories of deeply fulfilling are totally personal and unique to them. It’s different than knowing where someone lives, or what kind of food they like, or what sports team they root for. Those are not essential qualities of the person. (Well, they may be if you’re from Boston.)

The conversations don’t happen organically. There needs to be a process laid out—a context in which these conversations can take place. I typically model the process for my team with a handful of people. Once people see the storytelling and listening exercise modeled for them a few times, they’re able to do it on their own.

Are there things that make these conversations more or less effective?

Yes. That’s why it’s important not to throw people right into it. I run a half-day workshop on this topic for companies that are serious about implementing it well. I usually recommend they designate someone as “Chief Biographer,” and this person is responsible for overseeing the storytelling process. I dive into this process in detail and we model the session. The hope is that this leads to weekly or bi-weekly storytelling sessions between employees, one-on-one, throughout the year. Once the basic skills are learned, the exercise is transformational because it brings a new level of empathy to the entire organizational culture. And I believe empathy is the key to breaking out of negative mimetic cycles.

You draw an interesting distinction between “immanent” and “transcendent” leadership. Could you explain the difference?

Immanent leaders lead through imminent desire—in other words, there is no desire that transcends the system they’re in, and nothing that leads beyond themself. One example of an immanent leader—who is often thought of as a transcendent one!—is Ayn Rand’s famous character John Galt. He’s presented as a creative genius in the novel who organized a strike of the world’s great creative leaders. But Galt (and Rand), in the objectivist philosophy espoused in the novel, believe that all value is contained within the minds of those leaders—all progress, all ingenuity, all leadership starts and ends inside of their own heads. There’s nothing outside of reason, nothing outside their own skull-sized kingdoms. This is the definition of immanence from a philosophical perspective. I find John Galt to be a pathetic character. He’s arrogant, to be sure, but he also is willing to do harm (by organizing a strike) to prove to the world how much he and his fellow geniuses are needed.

A transcendent leader points to something behind themselves. They are aware of their own limitations. They are like the Level 5 leaders in Jim Collins framework in Good to Great. But transcendent leaders go far beyond that. There’s an objective dimension of work (literally what the work is); there’s a subjective dimension of work (what the work does to the worker); but there’s also a transcendent dimension (the purpose and meaning beyond the work itself)—and it’s the most neglected dimension. Transcendent leaders embrace it. Business, at the end of the day, is, to me, about loving and serving people. I don’t think that’s a utopia; I’ve seen that it’s possible. All it takes is a few transcendent leaders to shine a light and pave the way toward a more humanistic way of working. Because desire is mimetic, the desires of those leaders will spread by contagion. At least that’s what I’m hoping for.

“The health of an organization,” you write, “is directly proportional to the speed at which truth travels through it.” I find this an arresting observation, but I’m curious to hear more about the conversation you had with Louis Kim, a VP at Hewlett-Packard, that gave you that insight. You say you wanted to talk to him about how “mimesis manifests itself in more traditional corporate structures.” I’m eager to hear what Kim had to say about that.

The simple point that I came away with from that conversation is that a single leader can contribute to positive or negative mimesis in a way that impacts the entire organization. We sometimes forget that the truth itself—like lying—is mimetic. I’ve seen, like Louis, that honest and truthful leaders (who model what Kim Scott calles “radical candor”) can transform an organization in a short period of time.

Louis and I talked a lot about how shame is rampant in most big corporations. It might be the dominant (although hidden) emotion. People feel guilty about practically everything, or worry that they’re not measuring up. Shame makes us live in the dark. It makes us afraid of getting “exposed” or “found out.” People’s desires go underground. If they mess up, they begin finding ways to bury the mistake. It’s a spiral of deceit.

What do you think the most important role is for a leader?

The single greatest thing that a leader can do is to help people not feel so much shame in defeat—and to encourage them to speak truthfully. But most important: they cannot face or even worry about an existential threat (being fired). Once things become existential, everything changes. People need a certain amount of security in order to open up and tell the truth. This is true in a marriage, and it’s true in a company. There need to be strong bonds of trust and solidarity. One expression of doubt or frustration should not put someone at existential risk. There is no room for growth in that environment; everything is fight-or-flight.

You mention some simple experiments companies can do to test how fast truth spreads in their organization. Could you describe those, as well as other kinds of experiments you might know of that can reveal cultural shortcomings?

A simple experiment is to have someone “plant” a piece of inconvenient information in your organization—the kind that should make its way through extremely quickly, maybe even straight to the CEO. See how long it takes to make it—if it makes it all—but also see how distorted the truth is by the time it reaches the right people. This is a way to literally measure the “speed of truth.” I encourage companies to find out down to the second. Another tactic: observe a meeting with and without bosses and listen for the difference. You can also track what people do when they have a problem with a team member. Do they go to a central HR team or can they go straight to that person? Is gossip created? How long does it take for those two people to actually have a needed conversation? Is it even encouraged? That’s a cultural issue.

This doesn’t apply to cases like harassment, or other forms of reporting that should go through different channels in order to protect people, right?

Right. I’m speaking about the ability of people to have open and honest communication with other people. And it needs to be quantified. The speed at which those conversations happen contributes to the speed of truth. There’s a reason it probably travels fastest in the military special forces. They have skin in the game. They can’t afford not to. They maximize the speed of truth because their lives depend on it.

Brian Gallagher is the Communications Director at Ethical Systems. Follow him on Twitter @bsgallagher.