The Case for Diversifying the Prototypical Leader

Earlier this month, the commercial real-estate company WeWork, tarnished by financial implosion, hired as its new CEO an industry veteran, Sandeep Mathrani, who’s handled some remarkable turnarounds. He’s revived some suburban malls, for instance, the sort of place online shopping has largely put to rest. WeWork must be hoping Mathrani can work his mall magic for them. The company will, somehow, have to profit from office-space rent in an era when more and more people, like me, either opt to work from home or commute to a less-traditional office. Mathrani, according to Forbes, “could create a new WeWork model of ‘live, work, shop’—with a lot less play than the old WeWork model.”

This sort of opportunity—to shape the future of WeWork as its CEO—is one that he shares with a peculiar number of South Asians living in the United States. Sundar Pichai, of Google, is among them. As is Satya Nadella, of Microsoft. In fact, it turns out that in proportion to population size, more CEOs in the US are South Asian (Indian, Bangladeshi, or Pakistani) than are East Asian (Chinese, Japanese, or Korean) or even White. From 2010 to 2017, there were 2.82 CEOs per million South Asians versus 1.92 CEOs per million Whites and 0.59 CEOs per million East Asians. For South Asians in other words, the so-called “bamboo ceiling,” a phrase which executive coach Jane Hyun coined in her book on career strategies for Asian Americans, doesn’t apply. A new paper from researchers at Columbia University, the University of Michigan, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which compared the leadership attainment of East Asians versus South Asians in the US across nine studies, involving over 11,000 subjects, explains why.

It seems to come down to personality rather than prejudice or differences in motivation, the researchers found. I asked Michael Muthukrishna, a cultural psychologist at the London School of Economics, who wasn’t involved in the study, what he thought. “One thing that struck me,” he said, “is that South Asians face more discrimination, but are still overrepresented, which complicates a simple discrimination story.” East Asians just don’t tend to inspire the sort of confidence Americans want in a leader. It’s not their fault. Culture shapes personality. East Asians, strongly influenced by Confucianism, tend to lead in a style unfamiliar to most Americans, emphasizing humility, conformity, and harmony over self-confidence, outspokenness, and disputation. In East Asian cultures, assertiveness is often taken as a threat to group stability. “East Asians hit the bamboo ceiling because their low assertiveness is incongruent with American norms concerning how leaders should communicate,” the authors—Jackson Lu, Richard Nisbett, and Michael Morris—concluded. “The bamboo ceiling is not an Asian issue, but an issue of cultural fit.” Americans might be seeing East Asians’ aversion to assertiveness as a lack of confidence, motivation, or conviction, and their self-effacing approach could be closing off leadership opportunities they deserve. “To leverage diverse leadership talent,” the researchers say, “organizations should understand the differences among different cultural groups and diversify the prototype of leadership.”

Fostering a diversity of views and styles of leadership could give organizations, among other things, an ethical advantage. Leaders, for good or ill, can be one of the most important levers in an ethical system designed to support ethical conduct. That’s because they’re often seen by employees as role models, the organizational figures who demonstrate, through their conduct, the importance (or irrelevance) of ethical standards, choose whether to hold their employees accountable to those standards, and—crucially—design environments in which others work. If ideological diversity can, as research suggests, help teams work together more effectively, particularly when success depends on gathering information and deciding how to act on it, perhaps a diversity in leadership talent can offer more perspectives on how to inspire people to work creatively, effectively, and ethically.

Taking this notion seriously would mean halting or reversing a rather perverse trend in the hiring of East Asian leaders. In a 2018 paper, researchers looked at 4,951 CEOs across five decades, and found that companies hired East Asian Americans almost two-and-a-half times more often during a financial downturn compared to an upswing. This happens because of a few things. Hiring managers “prefer self-sacrificing leaders more when organizations are experiencing decline than success,” anticipate East Asian American leaders to be self-sacrificing and, as a result, believe that East Asian Americans are better suited to leadership roles when companies aren’t performing well. “Our findings suggest,” the researchers wrote, “that Asian American leaders are preferred under circumstances that are narrowly defined, short-lived, aversive, and provide them with little freedom to establish that they possess attributes that make them effective leaders in all circumstances—not merely during periods of decline.”

One might argue that this shows that East Asians aspiring to be leaders might benefit from interventions aimed at changing personality. Relatively flexible and malleable, personality traits are “actionable targets for policy changes and interventions,” researchers wrote in a 2019 paper. Of course, personality is one of the more challenging aspects of human behavior to reliably influence. As the researchers note, personality traits wouldn’t be “powerful predictors of outcomes in the domains of education, work, relationships, health, and well-being” if they weren’t, on the whole, stable. But that doesn’t mean they’re impossible to tweak. “Though trait change will likely prove a more difficult target than typical targets in applied interventions,” the researchers wrote, “it also may be a more fruitful one given the variety of life domains affected by personality traits.”

But to suggest East Asian-leadership style should be one such target of intervention seems not only unfair but short-sighted. The American prototype of a leader is to some degree an arbitrary construct, an abstraction inferred from personal experience with leaders and visible cues. “Although the stereotype that [East] Asian Americans are intelligent aligns with one key attribute of prototypical leaders,” the authors of the 2018 paper wrote, “characteristics associated with dominance, such as assertiveness and extraversion, are so central to the conventional prototype of a business leader that evaluators tend to perceive [East] Asian Americans as relatively unfit to lead.” To uphold the conventional prototype, as opposed to opening it up to be refined and enriched by new leadership talent from other cultures, would seem to close off an opportunity to make organizations more effective and—perhaps this goes without saying—ethical.

Brian Gallagher is Ethical Systems’ Communications Director. Follow him on Twitter @BSGallagher.

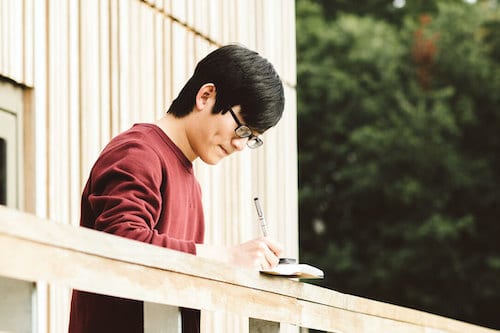

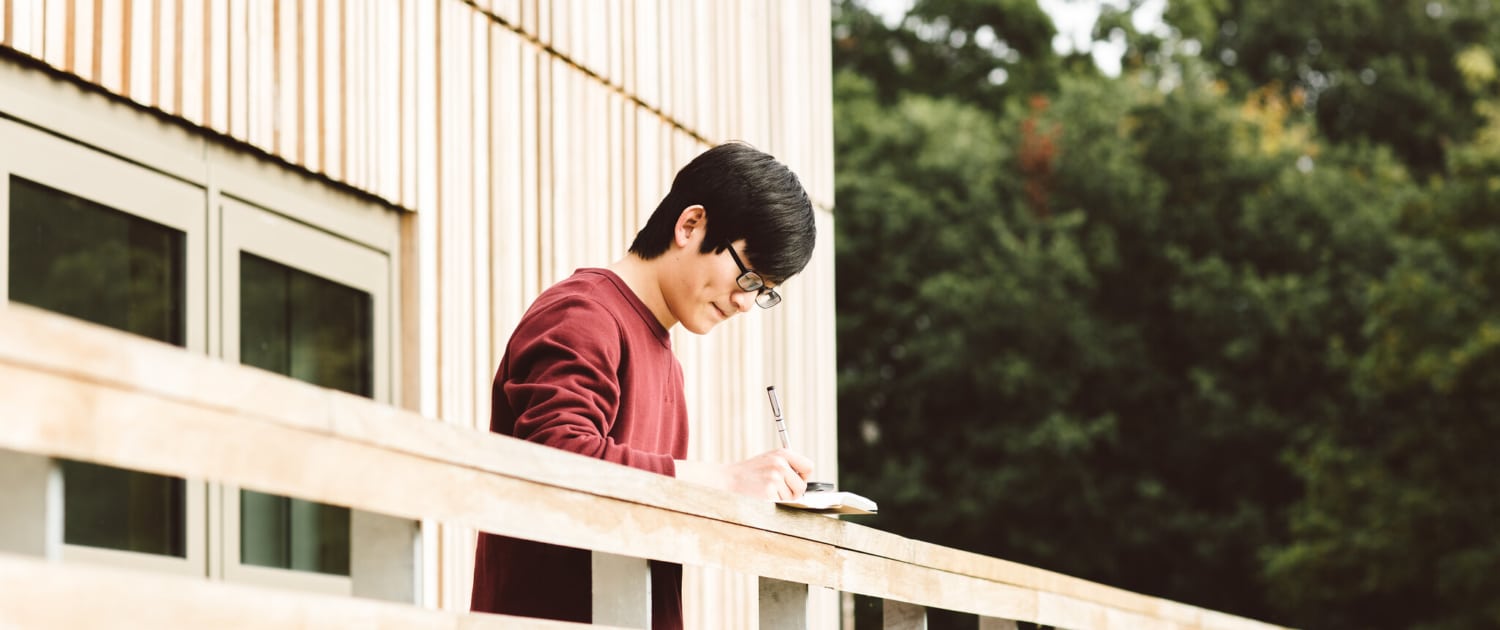

Lead image: University of Essex / Flickr