Ray Dalio and the Game Theory of Choosing Business Partners

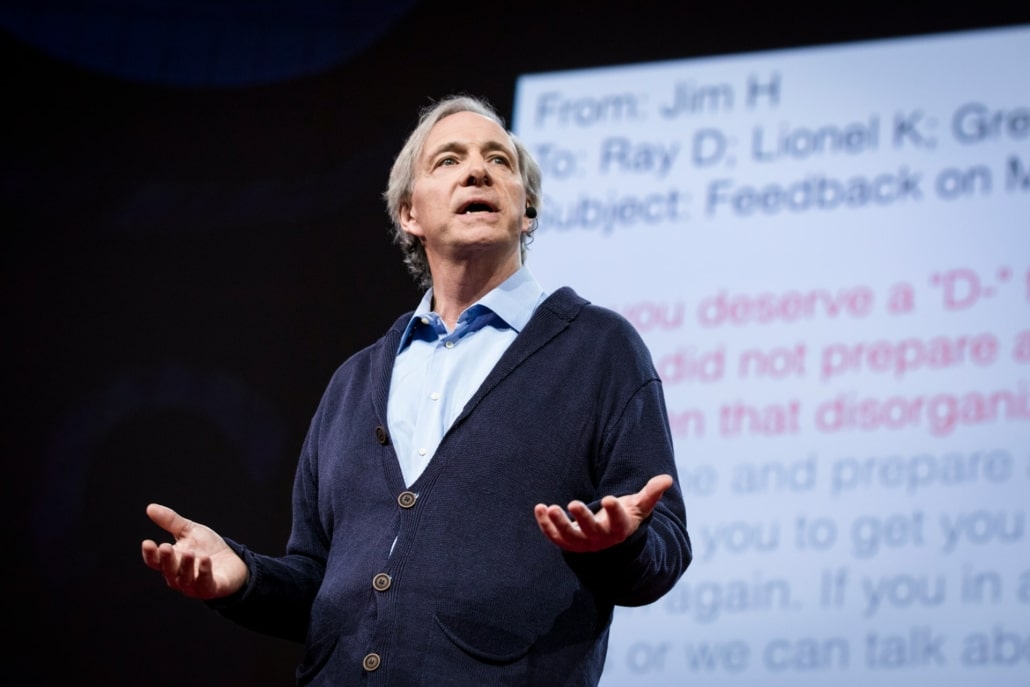

In his 2017 book Principles: Life and Work, the American billionaire investor and hedge-fund manager Ray Dalio offers some tips on choosing business partners. “In picking people for long-term relationships,” he writes, “values are most important, abilities come next, and skills are the least important.” Now, how does this bit of advice make you feel about Dalio himself? Does it burnish his reputation? Imagine he said abilities or skills were the most important, and values the least. Would that make you more likely, or less likely, to view him as a moral individual?

It’s not surprising to anyone that who you choose to do business with can affect your reputation. “You are known by the company you keep” is a familiar axiom. But why is this the case? Why does your choice of business partner say something about your own moral character? In a recent paper in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, my colleagues and I explain why.

Less cooperative people are less likely to sustain cooperative relationships over the long-term.

We drew on the partner choice literature to examine this. Partner choice is simply the act of choosing someone as a partner, whether it be a friend, business partner, or romantic partner. The common trade-off in partner-choice is between a partner who is better able to provide benefits, and a partner who is more willing to provide benefits. While the able partner provides more benefits in absolute terms, the willing partner is more generous because he is willing to share a larger proportion of his resources.

In a 2016 paper, Nichola Raihani and Pat Barclay reported one of the more striking findings in partner-choice psychology: When forced to confront the trade-off between an able partner and a willing one, over 50 percent of people forgo the greater benefits that come from the able partner, and instead choose the willing partner. From an evolutionary perspective, such costly behavior is puzzling. How could such behavior prove adaptive?

We drew on costly signaling theory. The central idea is that for a behavior to serve as a signal, certain types of people need to find the behavior too costly. For example, owning a luxury vehicle serves as a signal of high economic status, because people low in economic status cannot afford luxury vehicles. Likewise, choosing willing partners over partners who could offer more benefits or resources serves as a signal of moral character because less cooperative people cannot afford to do so. They don’t have the time.

Subscribe to the Ethical Systems newsletter

Why? Less cooperative people are less likely to sustain cooperative relationships over the long-term—their lower cooperativeness makes them more likely to eventually alienate a partner. As a result, less cooperative people are better off choosing the able partner, who provides them greater immediate benefits. More cooperative people don’t have this worry. They can likely afford to choose the willing partner. A willing partner might not provide such cooperative people with great immediate benefits, but the willing partner will provide them with moderate benefits that, over the long-term, can outweigh the instant windfall that comes from an able partner.

We tested this idea, beginning by seeing whether people perceive partner-choice decisions as cues of one’s moral character. We found that in an economic game, people are seen as less trustworthy when they choose partners who are less generous yet have more money to share. We then replicated this pattern of results when examining people’s decisions about what business partner to choose for a business deal and what classmate to invite to a social event. We also found that people indicate a greater desire to work for, consume from, and invest in a corporation who chooses to do business with a manufacturer that has a history of ethical treatment of its workers relative to a corporation who chooses to do business with a manufacturer that provides greater benefits to the corporation’s bottom line.

So, people seem to perceive partner-choice decisions as signals. But do people use their partner-choice decisions to signal to others? We found that people are aware that, by choosing certain partners, they will be signaling something about themselves, and we also found that who people tend to choose for a business partner fluctuates depending on the reputational incentives of their environment. When incentives favor appearing cooperative, people are more likely to favor willingness over ability in their business partners. Importantly, we also found that decisions around choosing a business partner vary based on time horizons. When people are asked to choose a business partner for a short-term relationship, a larger proportion choose the able partner; when asked to choose a business partner for a long-term relationship, a larger proportion choose the willing partner.

Are these signals honest, though? Are people who choose willing over able partners not only seen as more moral, but actually are more moral? We first examined whether people who choose willing partners behave more generously in an economic game, and we found that, indeed, they do. Such individuals on average share a larger percentage of their endowment relative to those who choose able partners. We also found that those who choose willing business partners score lower on psychometric measures of immoral personality traits, such as Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and narcissism.

Thus, by advising others to consider values over abilities and skills in others, Ray Dalio is not only providing sound business advice. He may also be signaling to others something about his own moral character.

Nathan Dhaliwal received his PhD from the UBC Sauder School of Business. His research focuses on reputation and the evolution of cooperation.

Lead image: TED Conference / Flickr