Is Donated Blood a Gift or a Commodity?

In the spring of 2013, my son, then 5 months old, became very sick. It took just under a month of anxious head-scratching before doctors finally diagnosed his condition as Kawasaki disease, an uncommon form of autoimmune inflammatory vasculitis.

Once his diagnosis was confirmed, he was treated through a procedure known as intravenous immunoglobulin therapy, in which antibodies collected from the blood plasma of between 1,000 and 10,000 donors are injected intravenously in the patient. To my partner’s and my relief, the treatment worked: He got better almost immediately.

Once this crisis had passed, I began to marvel at the incredible blood donation system that had made his recovery possible.

How did these trillions of potent proteins, originating in thousands of human bodies, find their way to my son’s blood circulation? What historical, social, and economic conditions enabled this extraordinary exchange of substances? As a social and medical anthropologist, these questions were the prisms that guided my subsequent dive into the fascinating world of the blood industry.

Donating blood was no longer seen as an individual act of generosity but as a way to participate in a collective society.

Blood has long been a focus for anthropological thinking. Anthropologists in the early 20th century were mostly interested in blood as a metaphor, a powerful symbol across cultures of vitality, kinship, sanctity, or defilement. In the past two decades, however, anthropologists began taking an interest not in the pristine symbolism of blood but in the actual substance—with all its red and gory messiness.

Anthropologists like myself find blood intriguing because of what it can reveal about a society: The specific ways the substance circulates outside and between bodies brings to light conflicting values, shifting political and ethical priorities, and the potentials and perils of economic systems.

These days, most of us take for granted that human blood can be extracted, stored, and infused in patients. But this hasn’t always been the case. The history of blood donation tells a remarkable and optimistic story of human altruism, ingenuity, and social organization—but also of greed, racism, and negligence.

BLOOD EXCHANGE OVER THE CENTURIES

So, let’s start from the beginning. When, how, and why did extracted human blood become seen as a public good?

As early as the 19th century in Europe, doctors began performing transfusions using human blood. At the time, blood transfusions were understood not only as a treatment for blood loss, but as a procedure that could potentially alter a person’s character. These attempts, however, were severely limited by physicians’ poor understanding of the circulatory system, crude equipment, and ineffective techniques. Many patients, as well as donors, died during these premature endeavors.

Then, in 1900, Karl Landsteiner, an anatomist in Vienna, discovered that human blood had different types, and the donor and recipient blood types needed to be compatible. In 1908, French surgeon Alexis Carrel devised a method for direct transfusion—suturing the blood vessels of the donor and recipient together—that warded off the dire effects of coagulation. In 1913, physician Edward Lindeman in the U.S. introduced a novel method of transfusion that involved inserting a hollow tube into the vessels of both donor and recipient, ridding doctors of the need to cut open any wrists. This made the practice much safer—and more palatable to potential donors.

Finally, in 1915, Richard Lewisohn, another physician from the U.S., introduced an effective chemical anticoagulant. For the first time in history, blood could be drawn from a donor’s vein, stored for a reasonable period, and transfused in the recipient at the medical staff’s convenience.

The notion of a blood reserve—a blood bank—suddenly became conceivable.

Yet the successful operation of blood transfusion on a large scale still had two final hurdles to cross. The first was logistical: Adequate systems had to be designed to support the creation of a blood bank. The second hurdle required a cultural shift: People had to recognize a moral precept to donate one’s blood for the sake of some greater good.

As with many cultural shifts, it was war that ultimately changed the public’s thinking on blood donation.

A blood system based on voluntary donations, and run by the state, is safer, more efficient, more economically viable, and crucially, more moral than its private-sector alternative.

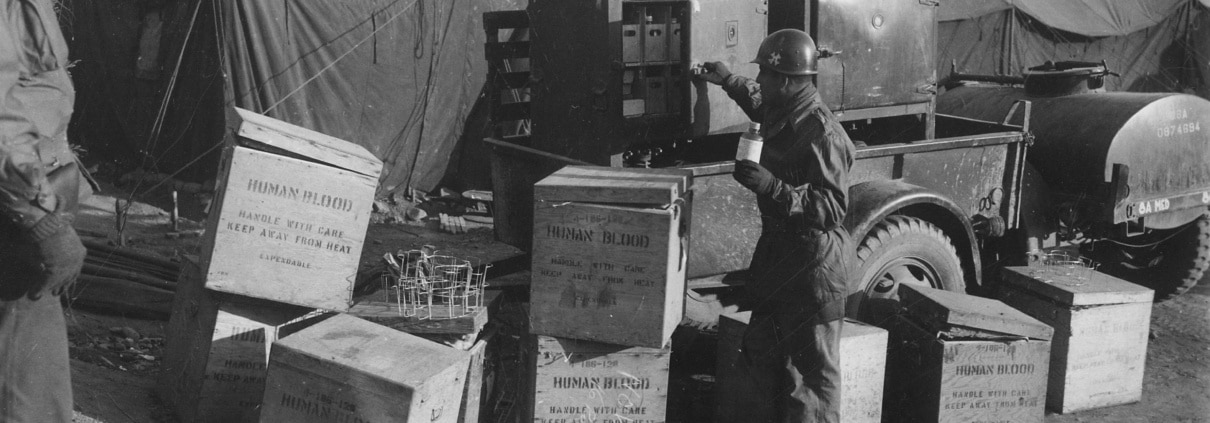

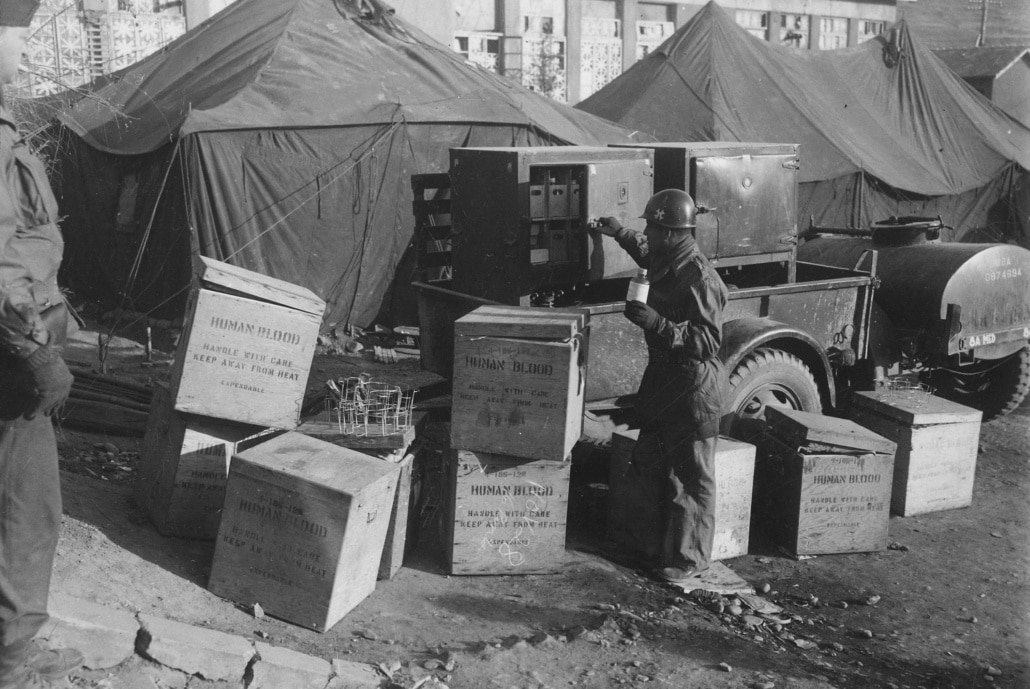

The first public health initiative involving a large-scale blood transfer operation occurred in Spain during the Civil War (1936–1939). Following a successful example from the Soviet Union (where hospitals began collecting and storing small quantities of blood from fresh cadavers), surgeons on the frontlines began operating mobile blood services using living donors.

A few years later, in the months leading up to WWII, a blood service started operating in London, subsequently saving thousands of lives during the German bombing campaign of the city. In the U.S., the Red Cross began collecting blood nationwide for military use in 1941.

These initiatives demonstrated both the need and the feasibility of an efficient blood donation service. But even more importantly, they charged the act of donating blood with powerful moral undertones. Donating blood was no longer seen as an individual act of generosity but as a way to participate in a collective society.

Subscribe to the Ethical Systems newsletter

THE RISE OF THE PLASMA INDUSTRY

In the decades that followed WWII, the U.K., France, Holland, and other countries still kept their blood services centralized and based on altruistic donation. Yet some countries, most notably the U.S., saw a massive decentralization of the blood economy. Blood itself was gradually reconfigured from a public resource to a commodity, bought and sold by private merchants for the sake of making a profit.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the blood business in the U.S. diversified to meet new medical demands for plasma. One driver of this demand was the discovery of new plasma-based treatments for hemophiliac patients. The other was the development of plasmapheresis, a therapy that involves the collection of plasma and the reintroduction of the red blood cells into the donor’s blood circulation.

The for-profit plasma industry boomed. Companies set up plasma-collection units mostly in impoverished areas, including along the Mexico-U.S. border—areas where an average price of US$10 for a pint of plasma (sometimes paid in liquor-store vouchers) seemed a lucrative transaction for many.

The most striking example of this new form of biological exploitation was the widespread collection of plasma from inmates in U.S. prisons starting in the 1960s. In Arkansas, for example, a controversial Prison Blood and Plasma Center started operating at Cummins prison in 1963. Inmates who had virtually no other means to earn an income were paid as little as US$7 for around a pint of blood, which the prisons subsequently sold for over US$100.

The hygiene and safety standards of these plasma swindlers were even more dubious than their ethical standards. Due to their lack of oversight, an epidemic of hepatitis began to spread in prisons where such operations were underway. Hepatitis then spread throughout the supply when companies pooled the plasma collected from thousands of donors as a way of cutting expenses—guaranteeing that so much as one infected unit would contaminate the entire pool.

Starting in the early 1980s, HIV made its way into the blood and plasma supply in a similar way. In 1984, the Center for Disease Control alerted the industry that blood transfusions seemed to be causing an AIDS outbreak among hemophilia patients. However, it took years for government regulations to fully prohibit the distribution of prison-sourced blood products. In Arkansas, prisons managed to find loopholes in federal regulations to continue selling extracted plasma abroad until 1994.

Total numbers are impossible to pin down, but experts estimate tens of thousands of hemophilia patients in North America, Europe, and Asia were infected with hepatitis C and HIV after being treated with contaminated blood and plasma from exploitative sources.

RICHARD TITMUSS’ LEGACY

This brief history of blood donation reveals how corporate greed, medical negligence, and structural inequality combined to turn an auspicious moral project into a global outbreak of HIV. Zooming out, it also points to how the blood industry as we know it today is contingent upon historical shifts, economic trends, and collective values—all of which are up for debate.

Enter Richard Titmuss.

Titmuss, a British scholar of social administration, conducted a comparative study of blood systems in the 1960s. In one corner was the British blood service. There, blood was treated as a community resource: donated freely and distributed by the welfare state. In the opposite corner was the U.S. blood system, where blood was sometimes freely donated and distributed by the American Red Cross, though more often sold by donors for a price and distributed by for-profit blood and plasma merchants.

Through a meticulous analysis of the two systems, Titmuss arrived at a definite conclusion: A blood system based on voluntary donations, and run by the state, is safer, more efficient, more economically viable, and crucially, more moral than its private-sector alternative.

The publication of Titmuss’ book, The Gift Relationship, in 1970 set off a series of events and public conversations that resulted in much stricter regulations of blood services in the U.S. Whole blood donations were effectively made volunteer-based with the introduction of new federal labeling practices.

However, most plasma collection was excluded from these labeling regulations. Today the global plasma industry is worth around US$24 billion, with demand continuing to outpace supply. Thousands of people in the U.S. who live under the poverty line continue to depend on income from selling their plasma.

Titmuss’ work remains relevant for understanding the meanings people ascribe to blood donation. Do donors understand their blood donation as a form of charity? A commercial exchange? A religious sacrifice? A fulfillment of their patriotic duty? An opportunity for spiritual atonement? An act of communal solidarity?

The anthropology of blood exchange tells us that the answers to these questions vary across national and cultural contexts. This variation matters because the values ascribed to blood go on to inform political systems. These values, which often reflect—and strengthen—preexisting biases and prejudices, shape policymakers’ decisions and ultimately determine the regulations that govern who can donate blood, who will be treated with it, and under what circumstances.

WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?

In many countries, regulating the blood industry has made its products safer—but it’s also led to new forms of disparities.

Some people are denied the right to donate blood based on their sexual behaviors, substance use, or where they come from. This form of selection sometimes has its public health justifications. But when certain groups (such as gay men, drug users, or some ethnic minorities) are excluded from donating blood, they are denied the right to express their civic belonging. Fortunately, this seems to be changing in some places. Canada, for example, recently lifted a nationwide ban on blood donations from men who have sex with men.

Preexisting biases and inequalities also shape who receives health care in different countries, including the medications and therapies that use blood products.

In other words, I may donate a pint of blood or plasma—but I have little say over where it goes once it enters the marketplace. If our national and global health care systems worked as they should, my donation would be acknowledged as a community resource and distributed freely to populations in need, including to those who are undocumented migrants or living in extreme poverty. But in our current systems, it’s possible my blood—or some components of it—would be assigned monetary value, bought and sold to the highest bidder to yield profits for the already affluent.

So, where does all this lead us?

On one hand, we shouldn’t fool ourselves into thinking that the systematic exchange of blood represents some utopic ideal based entirely on kindhearted gift-giving. Like any other human arrangement, blood systems are complex and morally fraught.

But we mustn’t be too cynical either. Even if our donated blood is sometimes commodified, it does ultimately save lives, as I learned with my son. And for that to keep happening, we must be willing to keep giving it.

Still, in donating blood products, we do earn the right to ask difficult questions about what precisely is being done with our precious cells and molecules.

Are our blood and plasma being handled safely—and morally? Is our donation accessible to those in need regardless of their ethnicity, nationality, or financial status? In short: Are the right people benefiting from our gift?

If the answer to any of these questions is no, then we as citizen-donors still have some work to do.

Ben Belek is a social and medical anthropologist. He is currently involved in sustainable policy design, acting as impact manager for the Israel Society of Ecology and Environmental Sciences.

Reprinted with permission from Sapiens.