How to Make ESG Investing Real and Meaningful

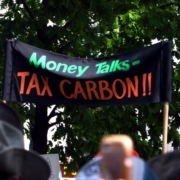

Attendees at the World Economic Forum in Davos recently made frequent references to ESG. An acronym for environment, social, and governance issues, ESG has become shorthand for what had been known as “corporate social responsibility” or “sustainability.” Judging from programs and conversations in Davos, there is a growing sentiment, at least in some quarters, that global companies need to pay greater attention to goals beyond maximizing short-term financial returns to investors.

Discussions of ESG sometimes seem confused because the concept actually has two distinct meanings. Many companies refer to ESG as a catch-all for their good works, ranging from supporting charities to reducing their carbon emissions. In the investment world, ESG is now commonly used to describe mutual funds and exchange traded funds (ETFs) designed to channel capital toward companies that meet certain positive criteria. In both contexts, ESG proponents tend to focus primarily on the environment, and specifically on what companies can do to slow global warming. Much less attention is paid to social concerns like the well-being of workers in global supply chains.

ESG investing can be improved greatly.

The largest institutional investors, firms like BlackRock, State Street, and Vanguard, now aggressively promote their ESG funds as vehicles for their clients to invest in companies that are protecting people and the planet. The giant financial firms typically also promise that ESG investments provide returns comparable to those of conventional funds. Based on this marketing, ESG funds have grown dramatically since the term was coined in 2004 and by one count now hold close to $35 trillion globally, or roughly a third of the total assets under management in the US and Western Europe.

For the first time in a decade there was a slight net decrease in monies invested in ESG funds in 2022, the result of a downturn in the market generally, the war in Ukraine and criticism of ESG investing by some political conservatives. According to Refinitiv, on average ESG funds lost 18 percent last year, underperforming the market generally which lost an average of 15.5 percent. This is because many ESG funds have had an outsized reliance on tech firms whose stock did poorly in 2022, and made less investments in fossil fuel companies that performed well.

Despite this cooling down, the growth of ESG funds over 15 years often has attracted breathless coverage in the financial press but also skepticism. Conservative Republicans like Governors Ron DeSantis of Florida and Greg Abbott of Texas have labelled ESG as “woke capitalism” and have taken steps to pull state pension money out of BlackRock funds in retaliation for the firm’s embrace of ESG. We’ll see more of this activity in the months ahead, as ESG becomes yet another wedge issue in an expanding culture war.

ESG also is being criticized, with good reason, for the absence of common definitions, especially for S; inadequate data; and insufficient systems for assessing compliance and building accountability. There is a vast gap between the way ESG funds are marketed by investment firms like BlackRock and State Street, and what they actually measure. The inclusion of fossil fuel companies in many ESG investment portfolios is one of many illustrations of this disconnect.

Some critics go so far as to say that the current incarnation of ESG is so flawed that it should be blown up. I disagree. While ESG investing can be improved greatly, if properly defined and applied, ESG frameworks have the potential to give investors with a commitment to environmental and social progress a means of evaluating companies by common standards. But it will require a much more serious and ambitious effort by firms marketing ESG investments and publicly traded companies generally to achieve this goal.

For ESG to realize its potential, three things need to change. First, investors and corporations alone can’t set the standards. Other stakeholders, like civil society organizations and academic experts, need to be involved. Today, investors are self-defining the S in their ESG investment frameworks, and corporations are doing the same in their own descriptions of company actions. In both cases, this allows them to pursue issues where they feel more comfortable and where they can use their own internal measurements of progress or compliance. On human rights issues—for example, labor rights in global supply chains—both company representatives who use the language of ESG to describe responsible conduct and financial firms that market ESG as an investment strategy react negatively to proposals to develop concrete compliance standards.

Subscribe to the Ethical Systems newsletter

Second, the discussion of ESG should focus on core business operations, not how companies respond to contentious political and social issues of the day. Companies can and will be pressed to weigh in on hot-button issues, but their responses should not be part of ESG frameworks. ESG should be focused on measuring corporate performance on clearly defined standards—such as carbon emissions for the E and the treatment of workers, including in supply chains, for the S. On a separate track, corporate leaders will need to decide whether to speak out on contentious social and political issues like voting rights, guns, and reproductive rights. But their decisions about whether and how to do so should not be part of the ESG framework.

Finally, once a common ESG standard is developed, it must be accompanied by a meaningful assessment system, based on much more and better data on corporate performance. A part of this data-collecting should look at internal corporate commitments and management systems—exercising due diligence of their internal processes. But having good systems in place does not necessarily translate into better performance. For companies with extensive global supply chains, for example, we need more rigorous and transparent assessments on issues like workplace health and safety, child and forced labor, and other subjects affecting the well-being of workers or the environmental impact of business operations.

Fortunately, government, especially in Europe, are moving in this direction. Earlier this month, a new German supply chain law went into effect. It will require all companies with annual revenue of 150 million euros to report on labor and environmental performance in their global supply chains. Several EU states also have adopted mandatory due diligence laws. While the term due diligence is yet to be clearly defined, the inclusion of this concept in binding national laws opens the door to a more standards-based approach. And the EU has adopted the Digital Services Act, which will require greater transparency from large tech companies on issues like how they are addressing content moderation.

In the U.S. last year, the Securities and Exchange Commission proposed a new reporting requirement on carbon emissions. It received a very large number of comments and is now being finalized. This year, the SEC is scheduled to propose a second rule on human capital, which hopefully will include reporting requirements on diversity and the well-being of workers in global supply chains. With a nudge from governments requiring the disclosure of more and better data, and greater regulatory oversight more generally, ESG can evolve into a meaningful basis for judging which companies are leaders in protecting people and the planet.

Michael Posner is the Jerome Kohlberg professor of ethics and finance at NYU Stern School of Business and director of the Center for Business and Human Rights. Follow him on Twitter @mikehposner.

Lead image: Ministério da Indústria, Comércio Exterior e Serviços / Flickr

Reprinted with permission from Forbes.