How do people change their minds about issues?

How do people change their minds about issues?

A respected colleague asked over lunch and it prompted me to write some thoughts down. Belief change and behavior change (page on that coming soon) can both be instrumental in ethical systems design so it seemed appropriate to share our Cliffs Notes on belief change here.

First, a caveat: some people are very dogmatic and exceptionally motivated not to change their minds. In those instances little can be done, aside from extraordinary circumstances providing an entry point. For the most reasonable people though, here are the highlights.

1) The situation has to be right. It is exceedingly rare for people to change their minds or admit they’re wrong when other members of their in-group are around. It’s hard to admit you’re wrong. It’s harder when your peers are around and it’s hardest when your peers are around and you’re emotionally aroused.

To get people to change their minds, the most effective way is through one-on-one conversation in a non-threatening environment when they’re not emotionally aroused.

2) Pay attention to social intuitionism and speak to the “elephant” first. One of the three main points of moral psychology is that intuitions come first and strategic reasoning comes second. Unless we have a system for doing otherwise, we pretty much just go with our gut feeling and then confabulate. This means we subconsciously come up with reasons to justify our position that our mind conveniently serves us as “reasoned” evidence rather than the knee-jerk response that it actually is.

In other words, the person has to like you, or at least not dislike you, before they’ll be open to your message. If the person doesn’t like you and you try to present your idea, it doesn’t matter how persuasive, articulate or evidence-based your comments are, they’re not going to change their mind.

This is one of the reasons why you can defeat every counterpoint that someone makes about your argument and they still won’t listen to you – you can’t intellectually bludgeon someone into changing their mind.

3) Make sure they have a full tank of willpower. Your odds of success will go up greatly if you’re speaking to the person when they have a full tank of willpower. Without getting into the details of it, willpower is like a muscle and tires out from a variety of things. One of the most important things for having sufficient willpower is having eaten recently.

If you want to change people’s minds, make sure they’ve eaten recently and don’t try to change their minds right before lunch or at the end of the day. There’s a famous study popularized in Willpower: Rediscovering the Greatest Human Strength that shows judges – who are supposed to be paragons of equanimity and effective decision making – granted far less parole when they made rulings right before lunch. They had decision fatigue and their willpower muscle was depleted and consequently they went with the path of least resistance. For someone to change their opinion they need to have a tank full of willpower. For more, see Roy Baumeister who has done some great work on willpower.

4) Acknowledge that their perspective is correct some of the time. One of the biggest problems with complex issues is that people can tell themselves stories that fit with whatever they want to believe. A lot of the time, the story they tell themselves is correct in some instances, but so is the story they don’t want to believe. You may find it useful to say something along the lines of “as you correctly pointed out” – speaking to the elephant first – before leading into the other story about how this other thing can also happen.

5) Attach the issue to someone they care about. Humans have a limited capacity for caring. A lot of the “harsh” judgments doled out by others are just because people maintain psychological distance (the underpinning of dehumanization) and don’t actually engage with the person or issue. If you want someone to engage with the issue, you need them to attach it to someone they care about otherwise they’ll maintain psychological distance and will feel comfortable offering flippant excuses for why what you’re saying isn’t accurate or really that important.

6) Change the frame and violate a schema. For example, if libertarians are framing taxes and regulation as theft it will trigger moral indignation. That’s fair. Anger is a natural response to a transgression. However, if you gently remind them you don’t want absolute freedom – and as our collaborator Robert Frank points out in the Darwin Economy: Liberty, Competition, and the Common Good, if they did Somalia would be a great place for them because people there are free to do whatever they want and there’s no government to intervene in anything – and that the opportunities they have to create value are based upon a functioning legal system that enforces property rights, you’ll have changed the frame and dismantled that otherwise impending moral outrage. This means they’ll be more open to your message. This will have also violated a schema, or altered how they view an issue, and then they’ll be more open to a new idea.

A lot of our judgments of situations depend on the stories we tell about the particular situation. Most complex issues are so vast that you can tell a horror story about something that doesn’t work or you can tell a success story about something that does and that both of them are right. Keep that in mind when framing, you can both be right.

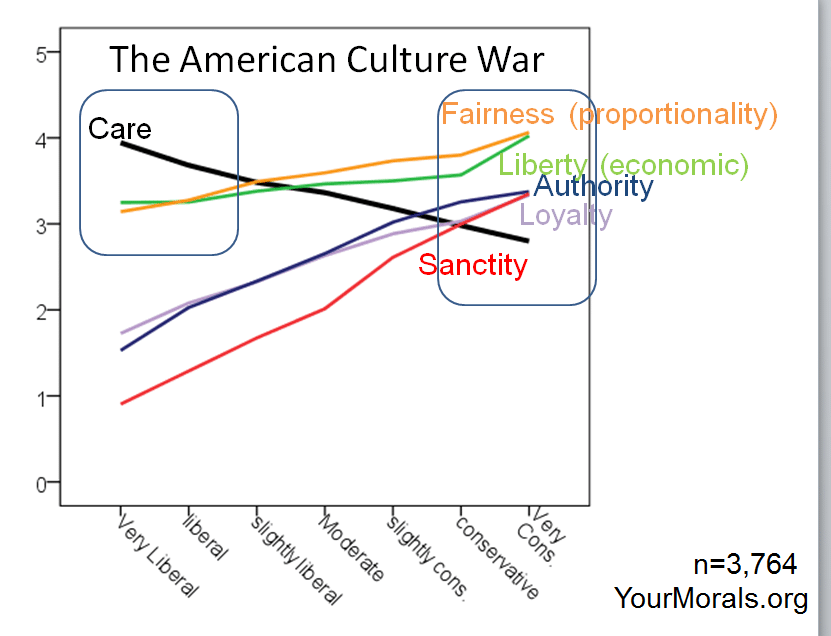

7) Appeal to the right moral foundation. We view the world through narratives. Our narratives are based on moral judgments. As it turns out, different people actually have different moral foundations, and libertarians, conservatives and liberals think different things are important (see graph below from yourmorals.org for example).

The most important moral foundation for libertarians is freedom. Liberals by contrast balance considerations between care/harm, fairness as equality, and freedom. Conservatives balance their understanding of right and wrong among fairness as proportionately, liberty, authority, loyalty and sanctity.

The least important moral foundation for conservatives and the most important for liberals is care/harm. In my opinion, that’s one of the reasons why a lot of the work of NGOs and the UN is a fraction as effective as it could be – they just keep on trying to explain care/harm more effectively when instead they actually have to appeal to different moral foundations if they want bipartisan support.

8) Induce the value self-confrontation condition as appropriate. Our lives and behaviors are replete with examples of inconsistencies between our actions and values that we don’t correct. If you can identify how someone’s values are inconsistent with their actions, people are much more likely to change their actions. For example, reminding a libertarian that freedom includes the freedom to choose one’s own beliefs, it would put them into the value self-confrontation condition, where they see their actions are inconsistent with their beliefs and (usually) correspondingly adjust their actions.

9) Pay attention to naïve realism. Your biases are invisible to you so it’s hard to understand the ways that predictable internal incentives distort information and make you a poorer decision maker than you would be otherwise. Essentially, naïve realism is the bias that makes us think that we see things objectively while others don’t.

It’s hard for people to understand that they’re not objective, and that they view things in a biased manner, because of tricks of the brain that they can’t see without some sort of experiential learning that actually demonstrates this to be true, but the research on this is sound. As Max Bazerman points out if you’re motivated by a particular outcome your brain will distort facts, unconsciously dismiss conflicting evidence and serve up biased evidence, as necessary, to make us comfortably reach our desired conclusion.

If you think you’re being rational but that others aren’t and they’re not objective, or are bad at thinking things through, that should be a signal to check your biases and see if naïve realism might be inadvertently influencing your otherwise excellent judgment.

10) Discuss some moral psychology – can I believe it versus must I believe it – and call it a day. When you want to believe something, you ask yourself “Can I believe it?” and it’s usually a yes and that’s where the analysis stops. When you don’t want to believe something, you ask yourself “Must I believe it?” and the answer is usually no and that’s where the analysis stops.

This is one of the most powerful ways that otherwise smart people can come to such opposing views on the same issue.

“Can I believe it?” and “Must I believe it?” are two very different questions that lead to very different frames of analysis and depending on whether you’re trying to believe something or disconfirm something, they’re both usually where the analysis stops – you can see how this would be problematic for reasoned consideration of an issue. Understanding that difference can help prevent people from engaging in motivated reasoning and promote a much more nuanced understanding of an issue.

Those are some of the major parts associated with getting someone to change their beliefs. There’s a much more detailed version of this story, and there’s a lot scholarship on the relevant factors scattered throughout academia, but those are some of the main highlights.