Evolutionary Thinking Can Help Companies Foster More Ethical Culture

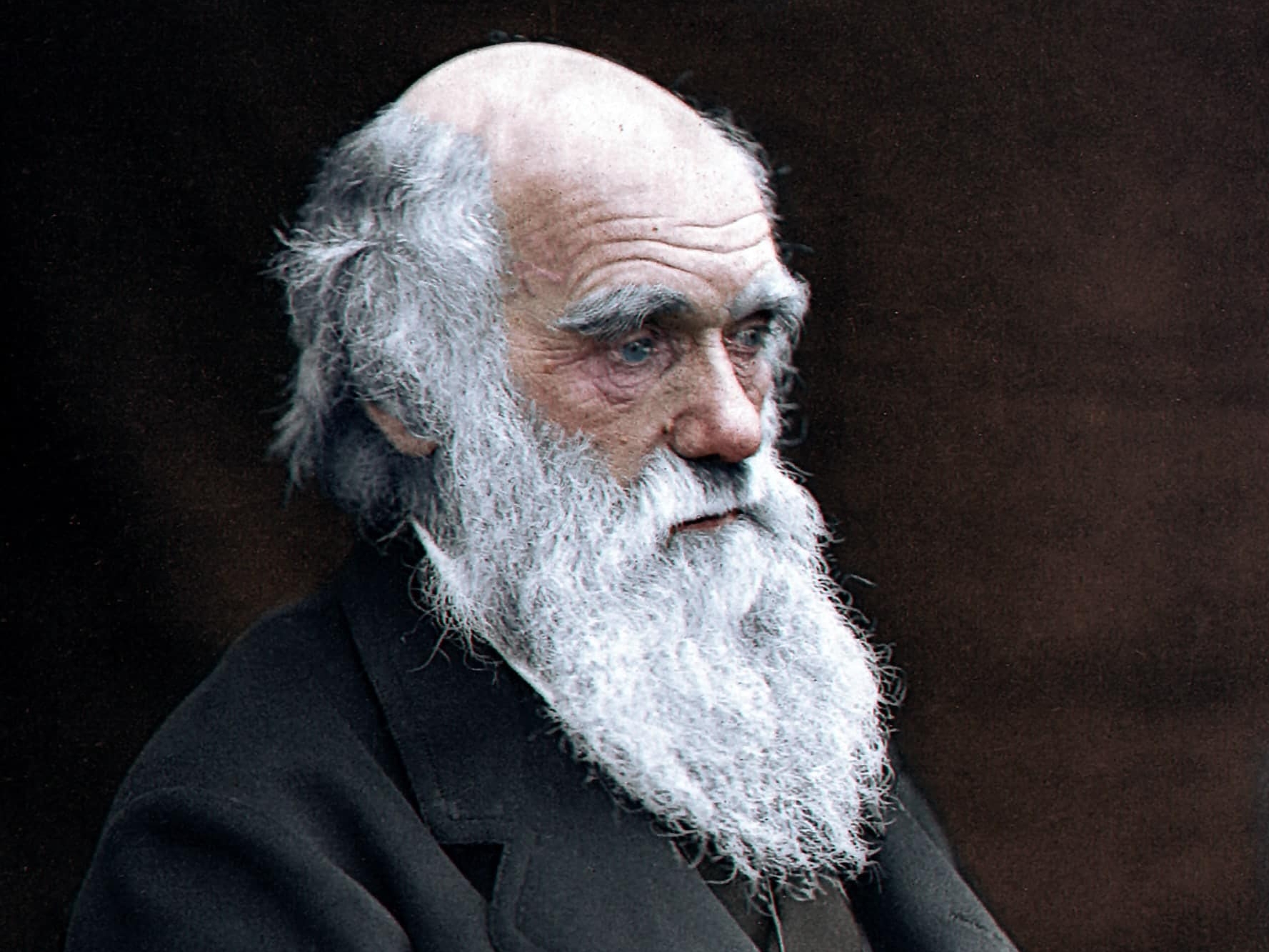

Charles Darwin ended The Origin of Species, his argument for evolution by natural selection, on a note of celebrated eloquence. “There is grandeur to this view of life,” he wrote, “with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.”

It is from this quote that a series of essays on business and management recently got its name. This View of Business: How Evolutionary Thinking Can Transform the Workplace offers a perspective, according to its three editors, that “can have profound implications at all scales, from the wellbeing of individual employees, to the performance of firms, to the creation of a sustainable global economy.” Ethical Systems spoke to one of those editors, Mark van Vugt, to find out how evolutionary insights can be valuable to business leaders and other professionals.

It is not surprising that we have a strong intrinsic preference to work in small, relatively flat and informal organizations.

Van Vugt is a professor of organizational and evolutionary psychology at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, where he co-directs the Leadership Lab. There he conducts experiments and surveys to discover the kind of leaders people desire in different contexts, like war and peace, and how effective these leaders are. He’s interested in how organizations function, and how people can improve them. “The inspiration and foundation of my research,” he told me, “comes from evolutionary sciences, especially comparative and anthropological studies, which give us a lot of insight into the nature of leadership and followership.” His latest book, co-authored with novelist and creative writing professor Ronald Giphart, is Mismatch: How Our Stone Age Brain Deceives Us Everyday (And What We Can Do About It).

What is the idea of “mismatch” in evolutionary theory?

There is often a time lag between an environmental change, deforestation or climate change, for example, and adaptations to cope with the change—that’s mismatch. The concept has been around in evolutionary biology for a while, and is one of the fundamental principles of evolutionary theory because natural selection operates on the basis of variations in how well organisms adjust to their environment. Mismatch may be very important for humans, too, because our environment has changed quite dramatically in a very short time, primarily as a result of our own doing. The cities we now live in, the way we communicate with each other, what we eat, how we choose our partners and leaders, the weapons we use, the way we work—these are all new phenomena to which our hardwired or, some say, Stone Age brains and minds may not be optimally suited. The result is a host of problems that affect our well-being, from lifestyle diseases to social inequality and environmental pollution.

How might human beings be mismatched to the modern business environment?

Many problems of the modern workplace have not been viewed through a mismatch lens, so at this point these are still hypotheses. But let’s take the role of managers, for example. Humans have a strong aversion to dominance, which is a result of our egalitarian nature that served us well in the small-scale societies in which we evolved. One of the biggest causes of job dissatisfaction, people report, is the interaction with their line manager. Many people find this relationship extremely stressful, as it infringes on their sense of autonomy, to be dominated by someone who controls them and gives them orders. Or take the physical work environment that looks nothing like our ancestral environment—our ancestors were always outside, working as they socialized and getting plenty of physical exercise while they hunted and gathered in tight social groups. Now we are forced to spend much of our daytime in tall buildings with small offices surrounded by genetic strangers and no natural scenes to speak of.

How can businesses avoid the worst effects of mismatch?

Humans have some basic needs that work should fulfill if organizations want to get the best out of them. People want to do work that is meaningful; they want some degree of autonomy in how they do their job, and they want to relate to others while doing their job. They don’t want to be anonymous or bossed around; they want to be able to participate in collective decision-making and keep their leaders in check. They also want to work in an environment that is not totally contrived, with easy access to nature. These recommendations come very close to the design principles for cooperative communities that were formulated by the late political economist Elinor Ostrom, based on her field work into how communities around the world effectively manage their resources, like fisheries or farmland, sometimes for generations. Organizations could learn a lot from these insights, and they are, luckily, becoming increasingly aware of the constraints of human nature. One of the tendencies we see, at least in the Netherlands, is an office environment with plenty of green around (plants and parks to take your lunch). Also, we know that power and status inequalities erode cooperation and trust within organizations, so they should be kept to a minimum. Instead of individual bonuses, it would make more sense to hand out team bonuses, for excellent work.

What is an example of a recent scandal or trend that illustrates how mismatch can hurt an organization?

There are various recent examples of organizations being damaged because their CEO’s wield too much power, a clear mismatch with our ancestral environment. Take the recent downfall of the CEO of Nissan/Renault, Carlos Ghosn, who has been accused of underreporting his salary package for a number of years. Analysts agree that the checks-and-balances on the CEO were missing in this newly established company that tried to merge two different car-company cultures.

You’ve written that evolutionary psychology has “implications for designing organizations that are perhaps better aligned with human nature than current structures.” What are the problems with the organizational structures we have now?

Organizations have an ambition to grow but as they increase in size, they also increase in complexity. So, in order to function properly they need to have multi-layered hierarchies and command-control structures to make sure that everyone is doing what they are supposed to be doing. The problem with scaling up is, first, the distance between the top executive and the work floor. Many strategic decisions made by the boardroom are done without a good understanding of what workers want and need. Ninety percent of mergers fail, for example, because the boards have not thought deeply about the consequences of putting two organizations with different cultures together. Another issue is the emphasis on shareholders. Organizations are held hostage by shareholders who want to see dividend payment. Research has found that organizations do much better, in terms of profits and job-satisfaction, when their employees are co-owners, like in cooperatives.

Subscribe to the Ethical Systems newsletter

Why do you say the appeal of boss-less organizations may be more than a fad?

Well, if we look at the popularity of these kinds of organizations, they get a lot of attention and interest from the media, and from the science community as well. Is this because they are fashionable or do these boss-less organizations have some sort of primitive appeal? Probably both are true to some extent. Our evolutionary heritage is built around small-scale organizations within an extended family network and at best two-layered hierarchies that were of a temporary nature. It is not surprising that we have a strong intrinsic preference to work in small, relatively flat and informal organizations. The current trend towards self-organizing teams reflect this. However, it is also true that as organizations get more success, and they grow and specialize more, then coordination is needed and hierarchies will inevitably form. So it may be true that boss-less organizations work in some markets—like with simple or novel products—but not in others.

What can business leaders learn from evolutionary psychology about how to structure relationships between bosses and employees?

One of the most important lessons from our research is that leaders are effective to the extent that they enable their teams to be effective. This sounds obvious, but leadership is really about the team and the followers. Individuals gladly follow leaders who they respect because of their skills and competence, and they have a hard time, by contrast, following a leader who is dominant and threatening. Yet human nature is also such that if you give someone power, they will use it—there is a fundamental leader-follower conflict. To keep managers from following the easy route of threat and dominance, every healthy organization should have mechanisms in place to curtail their power. In small-scale societies, as the anthropological literature makes clear, leaders are kept in check because they can only exercise influence in their domain of expertise, nothing else. What’s more, there should be room to gossip about and ridicule leaders, and leaders should be regularly replaced in order to prevent them building up a power base. Why not have feedback sessions where employees can provide regular inputs in the assessment of their bosses? Why not include workers in hiring board members? Many public and private organizations in Europe are currently experimenting with these power-leveling mechanisms.

Do CEOs and other managers have too much status and power now relative to more ordinary workers?

Too much power implies a moral judgment—what is too much? It is certainly true that power differences in the large public and private institutions are larger than what most people want. Surveys show that most people around the world are okay with CEOs earning 20-30 times more than the average worker, but the ratio in some big corporations is more like 200-300 times more. People don’t think that’s fair. The power differences are accentuated in the big organizations because there is fierce competition for positions in these steep hierarchies, and very few make it to the top. These winner-take-all competitions select for particular kinds of leaders—ambitious, dominant, perhaps narcissistic and maybe even psychopathic—who you do not necessarily want in the apex of your organization. More importantly, these steep competitive hierarchies are probably more aligned with men’s evolved social preferences than women’s, and this may form a real obstacle for them to climb up the ladder in these organizations. In our recent work, we refer to this as the glass-pyramid effect: the idea that women are more aversive than men towards working in large, hierarchical organizations. We have collected some evidence for this hypothesis.

How does Charles Darwin’s—not Adam Smith’s—invisible hand help explain the competition and survival among firms in the marketplace?

The classic economic model, inspired by Smith’s invisible hand, assumes that markets operate because individual actors are following their self-interest. But firms actually consist of multiple individuals working together, and if these are all following their self-interest, these firms could not function properly and would disappear. The brilliant insight of Darwin’s evolutionary theory is that competition and selection can happen at different levels of organization. This kind of thinking is called multilevel theory, and it is a fruitful way to think about not only social insects but also firms and markets. In the case of business competition, those firms prevail that are able to suppress the individual interests of their employees to the benefit of the firm’s interest. Individuals within a firm must be willing to cooperate with one another, and good firms have mechanisms in place to foster cooperation. Markets work better if competition is stronger at the level of firms than at the level of individuals within firms. This has obvious implications for salary and participation schemes within organizations that we are starting to explore.

Was there something in particular that fascinated you early on that explains your interest in this research?

My training in the Netherlands was in experimental social psychology, and my PhD research was focused on social dilemmas. I studied the conditions under which people are willing to contribute to public environmental goods. As I moved from the Netherlands to live and work in the UK, a less egalitarian and collectivistic country, I noticed that public-goods problems were dealt with very differently there. For instance, in the UK it is perfectly normal for welfare initiatives to be funded via the philanthropic activities of rich people, whereas in the Netherlands, that would be considered suboptimal compared to a tax system. That’s when I started to think more seriously about the role of hierarchical solutions, like leadership, to collective-action problems. And, as I started my transition to evolutionary psychology, while working in different psychology departments in the UK, I became interested in biological and anthropological approaches to social behavior, too.

Brian Gallagher is Ethical Systems’ Communications Director. Follow him on Twitter @bsgallagher.

Lead image: Julius Jääskeläinen / Flickr

This post was originally published in March 2019.