Elizabeth Holmes Is a Scapegoat—Even If She’s Guilty

Reprinted with permission from Luke Burgis’ Substack, Anti-Mimetic.

The criminal trial of Elizabeth Holmes, the founder of the blood-testing startup Theranos, began last week. As the trial drew near, I had a foreboding feeling that games would be played with the ideas of victim and victimizer — games that would leave many people, possibly even including the jury, confused about how to apply the law.

Understanding the sociological mechanisms that influence our perception of guilt has been my key work over the past several years. That’s why I was particularly interested when I heard from someone who had been involved in two separate lawsuits with Holmes—someone who understood the complex dynamics at work, and who was willing to cut through the popular narratives shaped by the media.

I met John Fuisz at The Berliner, an industrial-looking beer hall on the Potomac in Georgetown. We sat dry under the Whitehurst Freeway drinking beers while the rain from former hurricane Ida pummeled the street on either side.

The power of making someone or something a scapegoat stems from the fact that we think we’re actually ridding ourselves of a problem.

Fuisz is a former patent attorney; he was a primary source for John Carreyrou of the Wall Street Journal in his investigation of the medical technology company Theranos. As the public knows well by now, Carreyrou uncovered a massive scandal that sent the company’s $10 billion valuation to zero practically overnight, after it became apparent that the company’s major claims about its technology were false — and also after it had raised $700 million from investors. Its wunderkind CEO, Elizabeth Holmes, now 37, is on criminal trial on two counts of conspiracy to commit wire fraud and ten counts of wire fraud. If convicted, Holmes faces up to 20 years in prison, a $250,000 fine, and restitution to victims, which include medical patients and investors. Opening statements began last week at the Federal Courthouse in San Jose.

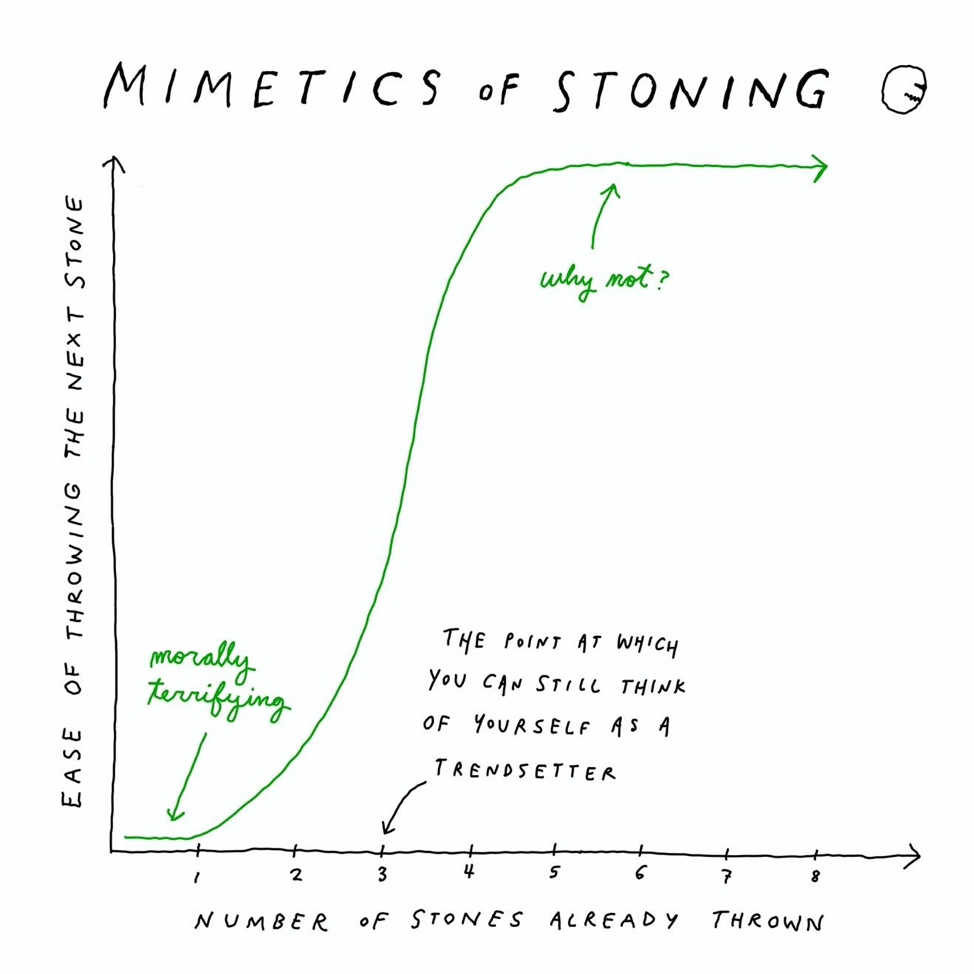

Our mimetic, or imitative, nature is what allowed Holmes to raise more than $700 million from investors—they imitated the desires of others they respected and then converge on the one person to blame when things went wrong. Mimesis on the way up; mimesis on the way down.

John Fuisz was sued by Elizabeth Holmes twice—once with his father Richard, a former CIA-agent and successful entrepreneur, and a second time as a partner at his then law firm, McDermott, Will & Emery. John prevailed in both cases, but he saw his legal career ruined by the process.

I found myself meeting Fuisz because he had just read my book, Wanting, after he saw a tweet from me about the Holmes case. He reached out, saying he had additional information on Holmes that he wanted to share with me — things he hadn’t told Carreyrou. A central theme of my book is the importance of listening to counter-narratives when looking for the truth. Fuisz felt like those counter-narratives were all being ignored in the Theranos case.

I’m not a journalist, I told him. “Yeah — hence the ping,” he wrote during our initial exchange. “Journalists bought into a story and need to write into that narrative. Challenge that view, and there is more there.”

Much of my research for the past three years has been focused on the tendency of people to respond to crises by finding a scapegoat: a single person or group on which to project their blame and to punish while exempting themselves from any part in the behavior. According to French social theorist René Girard, the process of making someone a scapegoat happens through mimetic, or imitative, behavior.

We are highly imitative creatures — far more than we are willing to admit. Our mimetic nature is what allowed Holmes to raise more than $700 million from investors; they imitated the desires of others whom they respected, neglecting to do proper due diligence. That same type of mimetic behavior also led them to converge on the one person to blame when things went wrong.

When I showed up to meet John Fuisz, I didn’t know what I was going to be walking into. In Carreyrou’s book about the scandal, Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup, Fuisz is painted as a hot-headed and litigious attorney. In one of the book’s most memorable passages, Fuisz is asked — at the end of a six-and-a-half-hour deposition — whether he suffered reputational damage, and how he feels about it. “Absolutely, I am more than pissed off at these people,” he said. “I intend to seek my revenge and sue the fuck out of them when this is over, and you can guarantee I will not let Elizabeth Holmes have another fucking company as long as she lives.”

The John Fuisz I met under the overpass at The Berliner seemed very different from the one in the book. He had lashed out at his deposition because he felt victimized by Holmes, he told me; now he saw that Holmes herself might be the victim of something bigger.

“Elizabeth and Theranos sued me twice and did a huge amount of damage to my wife, my children and me,” he said. “But what concerns me — as an attorney, and as someone who knows some of the facts first hand — is that mob mentality is undermining the justice system. The goal of the system has to be to expose the truth, not find an easy scapegoat. Elizabeth is an easy scapegoat.”

I have no interest in arguing for the guilt or innocence of Elizabeth Holmes. The attorneys will do the arguing; the jury will decide. I hope justice prevails. What I think is worth paying close attention to, though, is the power of what Girard called the “scapegoat mechanism”. It pervades our culture, and we will have to contend with it long after the Holmes trial is over.

Even so-called “cancel culture” functions as a form of micro-scapegoating. People mimetically move to accuse someone, “cancel” them, and experience some degree of catharsis from having done so.

We’ve been practicing the scapegoat mechanism for a very long time. In ancient Israel, each year on Yom Kippur, the high priest would receive two young female goats at the temple. One was sacrificed to God. The other goat, which was chosen by drawing lots, was special. Over this second goat, the high priest would symbolically transfer all of the sins of the people. Then, the animal would be collectively driven out of the city and into the desert to die.

This second goat came to be known as the “scapegoat,” the goat that escaped. The ritual act of expelling the goat — which the whole community was involved in — provided catharsis, or an emotional release, and exonerated them of their bad or unacceptable behaviors or their sins. René Girard found this pattern playing out in every culture in history, from the ancient Greeks to the Salem witch trials to the horrors of the Holocaust.

Not all incidents of scapegoating have quite such high stakes or horrifying consequences. Even so-called “cancel culture” functions as a form of micro-scapegoating. People mimetically move to accuse someone, “cancel” them, and experience some degree of catharsis from having done so. If it didn’t feel good, we wouldn’t do it.

Scapegoating only works if nobody participating in it knows that they’re involved in it. It only “works” as a social technology — as unethical as it may be — if it operates at the subconscious level. The power of making someone or something a scapegoat stems from the fact that we think we’re actually ridding ourselves of a problem.

The scapegoat mechanism works like a master magician. It diverts our eyes to the shiny object in the room so that we miss all of the things the magician is doing while we’re distracted.

Elizabeth Holmes became that shiny object. She liked being the shiny object, too, so long as she was being hailed as the founder of a revolutionary tech company. Now that people need to make sense of what went wrong, though, she has become the easiest target.

Peter Thiel, himself at risk of becoming a great scapegoat, writes this in his book Zero to One: “The famous and infamous have always served as vessels for public sentiment: they’re praised amid prosperity and blamed for misfortune. Primitive societies faced one fundamental problem above all: they would be torn apart by conflict if they didn’t have a way to stop it. So whenever plagues, disasters, or violent rivalries threatened the peace, it was beneficial for the society to place the entire blame on a single person, someone everybody could agree on: a scapegoat. Who makes an effective scapegoat? Like founders, scapegoats are extreme and contradictory figures.”

The problem with John Carreyrou’s book — and especially with the documentary film inspired by it — is the extent to which Elizabeth Holmes’s name has become synonymous with the fraud, so much so that it’s easy to forget how many other people were involved in some way, whether via formal or material cooperation, or just acts of omission: like a failure to do due diligence with investor money.

That’s not necessarily the fault of Carreyrou — it’s just something hardwired into who we are as humans. When most people familiar with the case talk about Theranos, they talk primarily about her. It’s as if society needs a single point of reference onto which to direct the blame. Any nuanced or contrarian voices are quickly filtered into a powerful surge of unanimity: all against one.

Subscribe to the Ethical Systems newsletter

The uncomfortable truth is this: even guilty people can be scapegoated.

In this kind of psychological environment, anyone who dares to offer a different perspective threatens the narrative and social cohesion of the group and possibly singles one out as “like” whoever it is who is taking on the guilt. This is why there are so few willing to defend those who are canceled, or accused, or deemed threats. The social forces dissuading that kind of action are powerful.

When I watched the documentary film about Holmes, The Inventor, I was immediately struck by how many people talked about Holmes’s personal oddities — her quasi-mystical ability to not blink for long periods of time, her low voice, her enigmatic office hours, her black turtlenecks. She was unanimously described as a strange outlier in terms of both her behavior and her intelligence. (The idea of Holmes as a genius emerged in the early days of Theranos. Everyone involved with the company at an early stage seemed to have what the late Steve Jobs was said to have, a “reality distortion field,” perpetuating a narrative that few chose to question with counterfactuals.) She was depicted as an extreme outlier in every respect, which is exactly what one would expect to find in a scapegoat. The features need to be extreme so that we can stay fixated on her.

But the fact that we scapegoat is one thing. The dizzying effects of the scapegoat mechanism in 2021 are another thing entirely. Because of our cultural awareness of injustice, there has been an inversion of the scapegoat mechanism that often makes it hard to see who is a victim and who is a victimizer.

According to Girard, since one of the most powerful narratives in the world is about a man who was unjustly crucified by an angry and irrational mob, today we have a heightened sensitivity to the plight of victims who suffer at the hands of others. Defending the rights of scapegoated victims has become one of our greatest sources of pride. But this is only the case if we actually believe the scapegoat is innocent. Obviously, we feel a strong responsibility to defend innocent victims; but we aren’t so quick to rush to the defense of those we suspect might be guilty.

The scapegoat mechanism falls on the guilty and innocent alike. The effectiveness of it isn’t reliant on the guilt or innocence of the scapegoat. It relies on a narrative psychology that is always able to justify itself after the fact.

The uncomfortable truth is this: even guilty people can be scapegoated. They can be used to fulfill some societal good, like emotional release. And that, too, is unjust. Not only because it means that a disproportionate amount of the blame and punishment falls to one person, but also because it causes us to overlook other, more systemic problems.

Scapegoating is a hell of a drug — but so is victimhood. We’re a society that sees that we’re unjust in various ways, so we have a keen eye toward anyone who seems like a victim. Machiavellian people have started to use the victim status to their advantage. “Victimism uses the ideology of concern for victims to gain political or economic or spiritual power,” wrote James G. Williams in the introduction to one of Girard’s books on the subject. “One claims victim status as a way of gaining an advantage or justifying one’s behavior.”

The truth is that someone can be guilty and be a victim at the same time, but it’s really difficult for us to hold both things in our heads at the same time.

In recent years, Holmes has painted herself as a scapegoated victim due to her gender and age. Her legal team is now arguing that she was a victim of abuse at the hands of the company’s former President and COO, Ramesh Balwani, whom she was in a relationship with beginning when she was eighteen years olds. (Balwani is scheduled to go on trial sometime next year for the same charges as Holmes.)

Indeed, she probably was. John Fuisz himself thinks Balwani deserves much of the blame: “Balwani was a 37-year-old married man who seduced a girl who literally just turned 18,” he told me. “Nobody should assume that that relationship was in any way healthy.” He reminds me that he has an eighteen-year-old child. For the first time in our discussion, he seems visibly emotional.

The truth is that someone can be guilty and be a victim at the same time, but it’s really difficult for us to hold both things in our heads at the same time. Perhaps this is the teetering edge on which real justice sits. We are always only one email away from vindication, one juror away from guilt, or two words (“I’m sorry”) away from peace.

“Even after I won my lawsuits against Elizabeth, she wanted some form of resolution with me,” Fuisz said. According to him, Holmes wanted a non-disclosure agreement from him so that he wouldn’t keep releasing information related to Theranos. But without an apology, he wasn’t going to sign anything. “I wanted a public apology. On March 16, 2014 at 8:41 pm, I received an email that she agreed to publicly apologize.” Fuisz says that within the hour, he received a second email. He is still not sure what happened between the two. “Whether it was Balwani’s influence or her pride, she changed her mind. There would be no apology, so no agreement.”

He is adamant: “She never apologized to me. If she had apologized in 2014, or if she had apologized to the world in any way, I think the public would have had a different view of Elizabeth. The question is whether her pride will prevent people from seeing what really happened.”

It’s hard for people to have sympathy for someone who has never been able to say they’re sorry. Former President Donald Trump famously bragged about never having to say he’s sorry while simultaneously claiming victim-status at the hands of the media. Most saw right through him. Will Holmes learn any lessons from this?

John Carreyrou doesn’t think so. He has launched a new podcast, Bad Blood: The Final Chapter, in which he suggests that everything Holmes does is manipulative, including her becoming pregnant and giving birth to a child earlier this year to become a more sympathetic figure to jurors. He recently tweeted that he will soon present evidence that subverts Holmes’ expected defense that she was a victim of Balwani. He seems to have taken on an unusual role for a journalist in actively shaping the public narrative around her guilt.

By contrast, when I spoke with John Fuisz, I noted his level of detachment from the case — a far cry from the angry man referred to in the courtroom who said that he wanted to take his revenge. He tells me that he has suffered greatly, but now he just wants to get on with this life. Since leaving behind his career as an attorney, Fuisz has founded a company, Veriphix. It is in the final stages of closing a seed round. Its mission: to help organizations and governments spot disinformation, and also effect and measure incremental changes in belief.

I’ve come to believe that — even if Holmes is convicted on all counts, even if she is guilty as charged — she is still serving as some kind of powerful scapegoat for Carreyrou and the public. She is playing her unique role in an ancient ritual.

Elizabeth Holmes started a medical technology company that harvested blood from people. Maybe it’s we who are out for her blood now. And not a finger prick, but a pound of flesh.

Luke Burgis is an entrepreneur and the author of Wanting, and writes about the intersection of Athens, Jerusalem, and Silicon Valley. Read his Q&A with Ethical Systems here.

Reprinted with permission from Luke Burgis’ Substack, Anti-Mimetic.