Bob Frank’s Legacy as a Teacher, Behavioral Economist, Economic Naturalist, and Author

In 1966, when Robert H. Frank arrived in Nepal to teach high-school math and science as a Peace Corps volunteer, he was surprised at how quickly he felt comfortable in his modest new home, even though conditions of life were dramatically different from what he was used to. “What was astonishing to me was that within a day or two, everything seemed normal,” Frank says. “You get up, you have things you want to get done that day, there are people you interact with … the day-to-day flow of life was really not in any meaningful way different.”

That experience was a defining moment for Frank that informed his outlook on life. “Knowing that when life is lived on a radically different material scale, it doesn’t much matter, is knowing something in a way that’s different from believing it to be true,” he says. “It’s sort of who you are, then.”

Frank, a professor of economics at Cornell’s Johnson Graduate School of Management, has written and spoken extensively about positional goods, cascading expenditures, inequality, and the ever-growing income gap in our society—all prevalent themes in his many books, essays, op-eds, media interviews, and podcasts. “Everybody knows that when the mansions get bigger, rich people probably aren’t much happier as a result,” he says. “Ordinary material conditions don’t do much to improve people’s lives when they happen across the board for everyone. We just get used to the new gadgets and bigger houses and more expensive wedding receptions. And they don’t have any lasting impact on our health or wellbeing or how happy we are.”

Many of Frank’s award-winning books, including Luxury Fever: Money and Happiness in an Era of Excess and The Winner-Take-All Society, co-authored with Philip J. Cook, are continually cited in both mainstream and business media outlets. Luck and the role it plays in people’s lives and the power of behavioral contagion are themes Frank expounds on in his most recent books, Under the Influence: Putting Peer Pressure to Work and Success and Luck: Good Fortune and the Myth of Meritocracy.

A Cornell professor since 1972, an influential teacher of economics, and a leading scholar who played a central role in bringing legitimacy to the study of behavioral economics at Cornell, Frank retired from the university on July 1, 2020.

An affinity for teaching

As a mathematics major at Georgia Tech, Frank, then an undergrad himself, had an unprecedented opportunity to teach an undergraduate math class and discovered he really enjoyed the experience. In fact, he liked it enough to shed the “stereotypical life history ambitious students at Georgia Tech envisioned to become president of a company before you were 40,” as he put it. “Being a teacher rose right to the top of my list,” he says, after “an advisor in the math department talked to me about it and said that his family lived quite comfortably. It didn’t mean signing an oath of poverty to become a teacher,” recalls Frank.

Subscribe to the Ethical Systems newsletter

So following two years of service in the Peace Corps, Frank studied micro, macro, and labor economics at the University of California at Berkeley, where he earned his MA in statistics and graduated with his PhD in economics in 1972, then interviewed for an assistant professor position in the Department of Economics in Cornell’s College of Arts and Sciences. “I was lucky to get that job,” says Frank. “They hired seven people that year and I was number seven.”

A maverick economist

Although he remained an economics professor in Arts and Sciences for nearly two decades—becoming a full professor in 1986 and a chaired professor in 1991—intellectually, it wasn’t the best fit from Frank’s perspective. “Economics departments vary from being overly concerned about mathematical formalism at one end of the distribution to obsessively overly concerned at the other extreme. Cornell’s department was near the obsessively concerned end of that distribution,” he says.

“I was able to do that kind of work; having been a mathematics major, that was not something that was daunting to me,” Frank says. “But the culture at Berkeley, where I’d studied as a graduate student, was quite different. There, they were concerned mainly with trying to get the right answer to whatever question they were posing. It wasn’t a matter of trying to prove how mathematically sophisticated they were; the ethos of that department was to use the simplest model that would get the job done.

“The Cornell department was not quite to my liking and my own career evolved in reaction to that,” Frank says. “I did what I had to do to get promoted; I published technical papers in the leading journals in sufficient quantity. But once I was freed from that, I spent the lion’s share of my energy working in a much more discursive mode, writing books. And I’ve been lucky to get away with that. That’s not the standard way that economists make any headway in the profession.”

Frank focused his work more and more on behavioral issues and continued to publish in untraditional ways. And he found an intellectual ally in Richard Thaler, who joined Johnson as a professor of economics in 1978. Frank says he and Thaler “spent a lot of time talking to one another about how the conventional economic models didn’t seem to describe the world we knew and experienced.” In 1990, when the Kellogg School at Northwestern offered Frank a chaired professorship, Thaler advised Frank to first take a half-time appointment at Johnson to find out how he liked teaching MBAs.

“I took the half-time appointment at the Johnson School and it was, in fact, a more congenial environment for me,” says Frank. “It was much more behaviorally oriented, and so I think it was a comfortable fit.” In 2001, he decided to join Johnson full time, while continuing to teach introductory economics in Arts and Sciences once every two years for many years. In 2002, Frank became Johnson’s Henrietta Johnson Louis Professor of Management and professor of economics.

A champion for behavioral economics

In 1989, Thaler, a professor of economics at Cornell for nearly two decades who later became a Nobel laureate in economics (2017), founded the Behavioral Economics and Decision Research Center (BEDR). It is an interdisciplinary center co-directed by Frank, among others, that “unites Cornell scholars who share a common interest in judgment, decision making, and behavioral economics.” The center is often cited as the birthplace of behavioral economics.

Behavioral economics challenges the “rational actor” model of human behavior. The “rational actor” model forms a big part of the core traditional economics curriculum, says Thomas D. Gilovich, Irene Blecker Rosenfeld Chair of Psychology and a co-director at BEDR. It is “based on the idea that people are perfectly rational and perfectly selfish, neither of which strikes a psychologist or behavioral economist as realistic,” says Gilovich, who became friends with both Frank and Thaler after joining Cornell’s faculty in the 1980s. “Bob was concerned that the focus on the rational actor as a description of human behavior just seemed inaccurate.

“Behavioral economics is an effort to draw on psychological insights about how the mind works and what people are like to inform models of economics that often left out those considerations,” says Gilovich. “So it’s a way to build a more realistic and therefore effective economics.”

“I also think of Bob’s legacy in terms of the strength of behavioral economics in the profession,” says Waldman. “When I first started, there wasn’t really anything called behavioral economics. In a sense, Richard and Bob created the field. And it’s not going away. Bob was an important contributor in making it a big part of economics, and it clearly fits in with what Bob was trying to do: Make economics more real.”

“As an economist, Bob is a big thinker and intellectual leader,” says longtime colleague and friend Michael Waldman, the Charles H. Dyson Professor of Management and professor of economics at Johnson. “He tries to re-orient the profession to be more realistic about how economies behave. Bob and Thaler built behavioral economics at Cornell and created fertile ground for behavioral economics champions like Ted O’Donoghue.” O’Donoghue, the Zubrow Professor of Economics and senior associate dean for social sciences in the College of Arts and Sciences, is also a co-director at BEDR. “Young behavioral economists at Johnson like Ori Heffetz and Marcel Preuss are part of Bob’s legacy in terms of the strength of behavioral economics on campus,” adds Waldman.

The genesis of the Economic Naturalist writing assignment

Most people don’t think of storytelling as a key, integral component to an introductory economics course. Frank does.

He describes the conundrum he sought to address in reforming the course: “Most students take only one economics course; mostly they don’t like it, and they don’t take any other [economics] courses. But more troubling is that six months afterwards, we give them tests that probe their understanding of basic economic principles and they don’t score any better than students who never took the course.”

Why? In Frank’s view, the reason was partly because introductory economics courses are overly mathematical, an approach he says is “not the best pathway” for students to understand basic economic principles. “Most people can absorb ideas most readily and efficiently if ideas are couched in a narrative, where there are actors, people with interests, a problem, a question to be answered, and a resolution,” he says. So he developed an assignment designed to get students to tell stories focused on applying economic principles in their answers to interesting questions.

“The title of the paper has to be a question—an interesting question based on something you’ve come up against in your own experience and that you’re curious about,” Frank would tell his students. “How do you know whether your question is interesting? Ask one of your classmates and see if they react in a way that signals interest. Do they want to know, ‘Yeah, why is that?’ Or do they blink dully and change the subject?”

Launched in 1987 with support from Cornell’s John S. Knight Institute for Writing in the Disciplines, over the years the assignment shrank from 20-page papers to narratives of no longer than 500 words. And Frank dubbed it the Economic Naturalist Writing Assignment.

“The reform for the course was to make a judgement up front about which six or seven ideas were the most important,” says Frank. “And in economics, at least, it’s fortunate that just a few ideas do most of the heavy work. Put those on display in as many contexts as possible and students can master them at a very high level in just a single semester.”

The proof is in the pudding, and hundreds of alumni have validated Frank’s approach by presenting him with the Stephen Russell Distinguished Teaching Award, which is given by fifth-year reunion classes to the Johnson faculty member whose teaching has most influenced them during their post-graduation years. “I’ve won that award four times,” says Frank, “and it’s by far the award I’m most proud of.”

“A lot of us try to teach everything, every detail is so important—‘what if I didn’t tell the students this? They won’t get the full picture,’” relates Ori Heffetz, associate professor of economics, whom Frank and Waldman interviewed and hired in 2005. “Bob was the opposite. Bob always said, ‘Less is more. Focus on a few core ideas and just keep hammering them in with more examples and more applications.’

“This was really influential for me,” says Heffetz.

When alumni honored Heffetz with the Stephen Russell Award in 2015, he says, “I thought, ‘This is Bob!’ The fact that five years later they still remembered insights from my course was because ‘less is more.’”

Why do kids need safety seats in cars but not planes?

Frank describes one of his all-time favorite economic naturalist essays, written by Greg Bellinger: “Why do regulators have you strap your toddler into a car safety seat to drive two blocks to Wegmans but then let you fly with your toddler loose on your lap when you fly from New York to Los Angeles?” As Frank says, “Greg reasoned that it had to be on the cost side of the cost-benefit test. And sure enough, if you have a safety seat in the back seat of your car, there’s no extra charge for strapping your kid in other than the few seconds it takes to do it. If you need to strap your kid in a safety seat on a flight from New York to L.A. and it’s full, you have to buy a seat—that’s a thousand bucks. So the cost of strapping your kid in a plane is much, much higher than the cost of strapping your kid in a car, and that’s why we see this difference.

“When you talk about that example with people,” Frank says, “then you understand the cost-benefit principle—which is probably the most important principle we have in economics—just a little better each time you do it.”

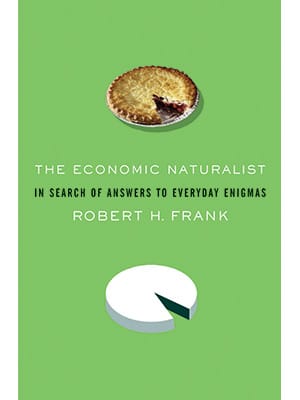

Frank compiled some of the best examples of students’ questions and answers into a book, The Economic Naturalist: In Search of Explanations for Everyday Enigmas (2007). It quickly became a bestseller in many countries, and sales around the world remain brisk more than a dozen years later. And as Frank wrote in the book’s introduction, he donated half his royalties from the book to the John S. Knight Institute for Writing in the Disciplines, “in grateful acknowledgement of my former students’ contributions … with full confidence that … no gift could more enhance the learning experience of future Cornell students.”

Thousands of economic naturalists

Ori Heffetz, associate professor of economics at Johnson, points out that Frank’s textbook, Principles of Economics, co-authored with Ben S. Bernanke and first published in 2001, is full of economic naturalist examples. In fact, as a co-author of the textbook since 2016 (it’s revised with new data and examples every year or two), Heffetz himself has written many economic naturalist question-and-answer summaries. Most recently, he’s been writing several about the coronavirus and its effects on the economy and unemployment for the eighth edition of the book, which will come out in 2021.

“There are now thousands of economic naturalists out there,” says Heffetz. “First of all, thousands of our alumni took Bob’s course and turned in two one-page economic naturalist summaries. Plus [there are] tens of thousands of users of the textbook.”

Frank’s ideas continue to gain currency partly because he is a master not only of writing about them in a way that’s clear, direct, and accessible to the layperson; he’s also adept at broadcasting his ideas in a variety of media. “Bob has had several big ideas in recent decades and he just hammered them in, like in his teaching,” says Heffetz. “He would write a book about them, then he would write about them in his New York Times column, then he would give interviews about them everywhere.”

Recently, Bob pushed for the next edition of Principles of Economics to include 10 short, animated videos that illustrate the best of the economic-naturalist examples, says Heffetz. “So the publisher hired animators and they are making a high-quality production of short videos that you can tweet and that can go viral.”

Context matters and relative wealth

“Speaking selfishly as a social psychologist, I will say that Bob is a social psychologist masquerading as an economist,” quips Gilovich, who is Frank’s longtime friend, research collaborator, and tennis partner. “The biggest lesson of social psychology is that everybody’s behavior is very finely tuned to the environment in which they find themselves. We’re sophisticated beings with sophisticated brains that pay attention to the tiniest details of our surrounding circumstances.

“That is to say, context really matters,” Gilovich says. “And almost all of Bob’s work has illustrated the importance of that idea in various ways.”

As an example, Gilovich points to one theme in Frank’s research: the idea that absolute wealth is important, but nowhere near as important as relative wealth. “How you’re doing relative to the people around you is more important to your happiness and is a more important driver of your behavior,” says Gilovich. “Bob illustrated this in his first and absolutely delightful book, Choosing the Right Pond. It continues through Luxury Fever and many of his New York Times columns. And it’s in his most recent book on context, Under the Influence.

“Someone who thinks about human behavior as attuned to the social context is a social psychologist,” Gilovich jokes, summing up. “So for my field, I’m just going to claim Bob Frank.”

On a personal note, Gilovich adds, “Bob’s got a delightful, self-deprecating sense of humor, he’s tuned into all the amusing things that life offers, doesn’t miss a beat, and has a great wit in commenting on everything going on around him. He’s always giving other people credit, and he’s just a magnificent human being.”

Post-retirement plans include lectures, podcasts, and essays

While he may be retired from Cornell, Frank has “enthusiastically signed up,” says Gilovich, to teach a BEDR class on decision making—a class that he and other BEDR co-directors have taught above and beyond their regular teaching load over the last two years.

Frank fully plans to continue publishing his ideas in The New York Times, the Washington Post, The Atlantic, and other outlets. He’s continuing to speak in video and podcast interviews. And he’ll continue to post to Twitter (@econnaturalist), a venue he has found to be effective for developing ideas that he later polishes and publishes as essays.

“A couple of pieces I published recently grew out of threads I first posted on Twitter,” Frank says, “just because that’s a place for getting started. The hardest part of any project is to get started. Once I get started on a book it’s all I can do to keep from working obsessively on it. The first thing I want to do in the morning is read what I wrote yesterday and then get going on it again.”

So stay tuned.

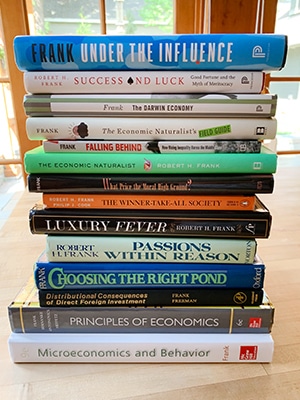

Books by Robert H. Frank

Many of Frank’s books are best-sellers around the world. Translated into 24 different languages, they are approachable and understandable for a general audience and have won multiple best book and notable book awards. They underscore the inequality inherent in our society and propose new tax structures that would address this. They clearly and vividly illustrate terms like expenditure cascades, positional goods, and behavioral contagion. And they discuss the role sheer luck plays in people’s lives. Here’s a list.

Under the Influence: Putting Peer Pressure to Work (Princeton University Press, 2020)

Success and Luck: Good Fortune and the Myth of Meritocracy (Princeton University Press, 2016)

The Darwin Economy: Liberty, Competition, and the Common Good(Princeton University Press, 2012)

The Economic Naturalist’s Field Guide: Common-Sense Principles for Troubled Times (Basic Books, 2009)

Falling Behind: How Rising Inequality Harms the Middle Class (University of California Press, 2007)

The Economic Naturalist: In Search of Explanations for Everyday Enigmas(New York: Basic Books, 2007)

What Price The Moral High Ground? How to Succeed without Selling Your Soul (Princeton University Press, 2004)

Principles of Economics, with Ben S. Bernanke, and with Kate Antonovics and Ori Heffetz in later editions (McGraw-Hill, first edition, 2001; eighth edition, 2021; brief edition, 2008; fourth brief edition, 2021)

Luxury Fever: Money and Happiness in an Era of Excess (The Free Press, 1999; Princeton University Press paperback edition, 2000)

The Winner-Take-All Society: Why the Few at the Top Get So Much More Than the Rest of Us, with Philip J. Cook (Martin Kessler Books at The Free Press, 1995)

Microeconomics and Behavior (First Edition, McGraw-Hill, 1991; Tenth Edition, 2021)

Passions Within Reason: The Strategic Role of the Emotions (W. W. Norton, 1988)

Choosing the Right Pond: Human Behavior and the Quest for Status(Oxford University Press, 1985)

The Distributional Consequences of Direct Foreign Investment, with Richard T. Freeman (Academic Press, 1978)

Janice Endresen is the Communications Editor at Johnson Graduate School of Management at Cornell University. Follow her on Twitter @JSeditor.

This article was originally published on Cornell Enterprise, and is reprinted with permission.