Bandits Are Losing Interest in Robbing Banks, As Some Crimes No Longer Pay

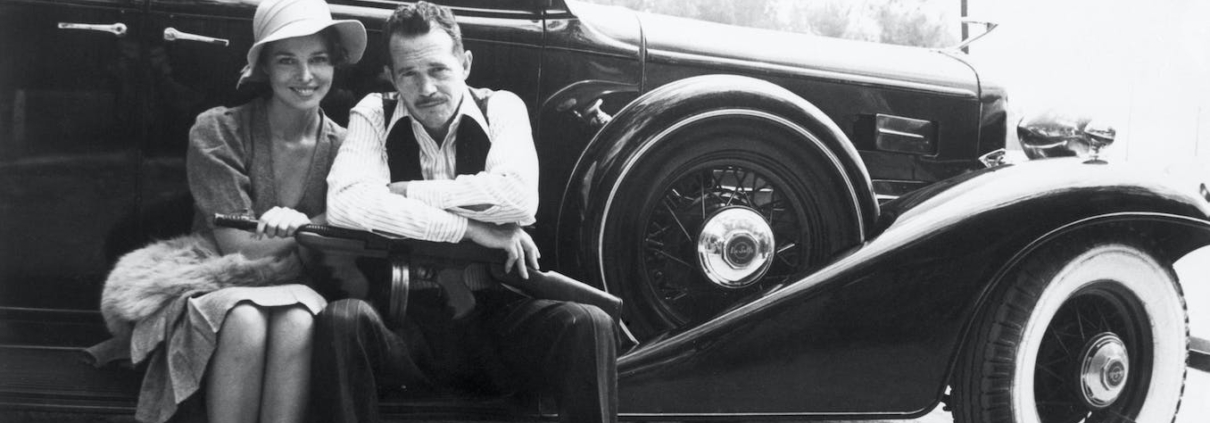

Bank robbery is a high-profile crime that fascinates many people. Movies have been made about famous bank robbers like Bonnie and Clyde, JohnDillinger and Butch Cassidy. There is even a new movie that just came out about Gilbert Galvan, Canada’s most prolific bank robber, who robbed 59 banks in five years. It might surprise you—as it did me—to learn that the number of bank robberies is the lowest it’s been in half a century.

That’s what I discovered while researching a book about the shift to a cashless economy. With people using less cash, I had expected fewer bank robberies. But I was startled to see that the downward trend started well before the cashless economy started springing up in the 2000s.

“The return on an average bank robbery is, frankly, rubbish.”

Movies often depict bank robbery as precision plots planned by smart crooks. However, this doesn’t match reality. Most bank robberies are committed by people simply walking in and demanding money from a teller.

In 2021, about 85 percent of bank crime was committed at the tellers’ counter. The vast majority of thieves either passed a note to the cashier or made a verbal demand. Very few incidents involved burglary, when a thief enters the bank during nonbusiness hours, or larceny, when money is stolen with no direct confrontation with employees.

Over half of all cases involve a weapon being brandished or a threat to use one. This results in many bank robberies becoming traumatic and dangerous events for employees and customers in the bank. Since 1999, 15 people have been killed in bank robberies, 94 were injured, and 62 were taken hostage.

Law enforcement contributes to the mystique of bank robbery by giving many robbers interesting nicknames, as you can see from the FBI website devoted just to them. For example, the FBI is offering $2,000 for information leading to the arrest of the “Bling Ring Bandit,” who stole an undisclosed sum from a bank in Albuquerque, New Mexico, while wearing a large gold-colored ring on his right little finger. My favorite is the “Ninja Bank Robber,” who was covered in black from head to toe during his April 2022 robbery.

Because there are different types of bank robberies, there are a variety of prison sentences for those caught. Robbers using force or violence get a maximum sentence of 20 years. Hurt someone while robbing a bank and the maximum sentence increases to 25 years. Kill someone and face death or life imprisonment. Robbers who don’t use weapons face less time. Robbing a bank of more than $1,000 without using force is a sentence of up to 10 years. Stealing less than $1,000 without force has a maximum sentence of only one year.

Bank heists are going out of style

The FBI has been tracking bank robberies and other crime in the U.S. since the 1930s. Unfortunately, early data was based only on voluntary reports from police chiefs of very large cities. Moreover, early data was not standardized when multiple offenses were committed, like bank robbers who stole a getaway car.

This resulted in very low figures, like 1948 having only 53 bank robberies. Higher-quality bank robbery data began around 1970, when the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports reported just over 2,000.

The number of U.S. bank robberies peaked in 1991 when 9,388 where committed. The number has declined pretty much ever since. By 2021, it was just 1,724 after hitting a 51-year low of 1,500 in 2020.

Subscribe to the Ethical Systems newsletter

A less lucrative career path

One potential reason for the downward trend could be that punishments have increased, thus acting as a deterrent and convincing would-be bank robbers to find another line of work. This reason doesn’t hold up, however, as the data shows judges are giving shorter, not longer, sentences. A 2021 analysis found the typical bank robber, most of whom used guns, was sent to prison for fewer than seven years. A mid-1980s study put the median sentence at 10 years if a gun wasn’t used, and 15 if a gun was involved.

Another explanation could be that there are fewer banks to rob. After peaking at over 85,000 in 2009, the number of bank branches in the U.S. has declined to a little over 72,000.

A more compelling reason for me is that robbing banks has become far less lucrative—after adjusting for inflation, anyway. The typical robber made away with about $5,200 in the late 1960s. That’s over $38,000 in 2019 dollars. But in 2019, the average was just $4,200. As a 2007 U.K. study on the topic noted, “The return on an average bank robbery is, frankly, rubbish.”

As it turns out, cyber heists are much more lucrative, with even fewer penalties. A government report showed that in 2016, convicted credit card offenders took in over $60,000 on average and were given a prison sentence of just a little over two years.

Willie Sutton was an infamous U.S. bank robber during the 1920s and 1930s. When asked why he robbed banks, Sutton supposedly replied, “Because that’s where the money is.” While in Sutton’s time that may have been true, it may not be the case today.

Jay L. Zagorsky is a clinical associate professor at Boston University.

Lead image: Bettmann via Getty Images

Reprinted with permission from The Conversation.